Last updated on 2025/05/03

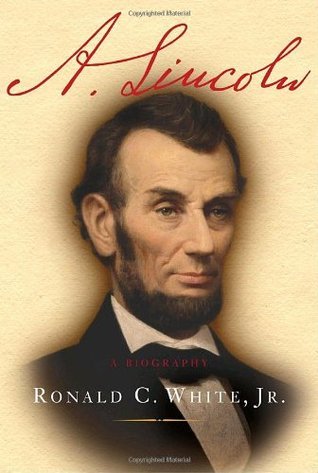

A. Lincoln Summary

Ronald C. White Jr.

A Portrait of the Great Emancipator's Humanity

Last updated on 2025/05/03

A. Lincoln Summary

Ronald C. White Jr.

A Portrait of the Great Emancipator's Humanity

Description

How many pages in A. Lincoln?

816 pages

What is the release date for A. Lincoln?

In "A. Lincoln," Ronald C. White Jr. offers a deeply insightful and nuanced portrait of one of America's most revered leaders, delving into the complexities of Abraham Lincoln's character, his moral convictions, and the tumultuous times that shaped his presidency. White meticulously weaves together historical events, personal correspondence, and Lincoln's own reflections to illustrate the profound evolution of his thoughts on slavery, democracy, and the meaning of the Union. This illuminating biography not only celebrates Lincoln's extraordinary leadership during the Civil War but also challenges readers to consider the values of empathy, humility, and resilience that continue to resonate in today’s political landscape. By inviting us to walk alongside Lincoln during pivotal moments, White makes a compelling case for why the legacy of this remarkable man is more relevant than ever in our quest for justice and equality.

Author Ronald C. White Jr.

Ronald C. White Jr. is a distinguished American author and historian renowned for his rich exploration and interpretation of the life and legacy of President Abraham Lincoln. With a Ph.D. from the University of California, Los Angeles, White possesses a deep academic grounding that complements his engaging writing style, making complex historical narratives accessible to a broad audience. His extensive research and thoughtful analysis are evident in his acclaimed works, including "A. Lincoln: A Biography," where he delves into Lincoln’s moral and political journey while providing insights into the tumultuous era in which he lived. White's commitment to illuminating historical truths and his ability to weave personal and political dimensions of historical figures have established him as a leading voice in Lincoln studies, enriching our understanding of one of America's most revered presidents.

A. Lincoln Summary |Free PDF Download

A. Lincoln

Chapter 1 | A. Lincoln and the Promise of America

In Chapter 1 of "A. Lincoln" by Ronald C. White Jr., the author explores the complex identity of Abraham Lincoln, a figure who has captivated American imagination for generations. Lincoln's name, inscribed simply as "A. Lincoln" on his Springfield home, symbolizes his enduring enigma, one that defies easy categorization or understanding. This chapter delves into Lincoln's multifaceted character, his values, and the perceptions shaped by both supporters and detractors throughout history. 1. The Elusive Identity of Lincoln: From the moment of his rise to prominence, Lincoln has been a subject of intense public scrutiny. His appearance, contrasting sharply with the founding fathers, often drew remarks—like Walt Whitman's description of his face as "so awful ugly it becomes beautiful." However, it was his speech that truly mesmerized audiences, allowing them to overlook his unconventional looks. 2. Honest Abe and Dual Perceptions: His early reputation as "Honest Abe" was solidified by his commitment to repaying debts, showcasing his moral integrity. Concurrently, political rivals created derogatory labels to undermine him, reflecting the polarized perceptions of his leadership. As he navigated the Civil War, affection grew for him among troops, who came to know him as "Father Abraham," culminating in the revered title "the Great Emancipator." 3. Understanding Lincoln’s Self-Definition: Unlike many public figures, Lincoln left few personal writings to define himself. He wrote sparse autobiographical statements and rarely shared his inner thoughts, which factored into his public persona. Lincoln’s law partner remarked on his reticence, leading to a dynamic where his compelling public speeches contrasted sharply with his reserved nature. 4. Confronting Contemporary Questions: Each generation re-engages with Lincoln's legacy, raising new inquiries about his stance on critical issues such as race, the presidency's role, and his relationships, especially with his wife, Mary Lincoln. These evolving questions uncover further layers of complexity in Lincoln's life, suggesting a man intertwined with both benevolence and conflict. 5. The Private Thoughts of a Public Man: Though he did not maintain a traditional diary, Lincoln kept notes filled with reflections throughout his life. These fragments reveal a man grappling with philosophical and moral dilemmas, showcasing his intellectual depth and evolving understanding of slavery and America’s national identity. 6. Moral Integrity as Lincoln’s Foundation: Central to Lincoln’s character is his moral integrity, steeped in influences such as nature, literature, and religious texts. His ambition, however, required moderation and balance throughout his political career; he often faced the need to reconcile personal ambitions with communal expectations. 7. A Comfortable Embrace of Ambiguity: Lincoln’s approach to issues was characterized by an acceptance of ambiguity, illustrating his legal training and his ability to view problems from multiple perspectives. This trait enabled him to understand and appreciate differing opinions, even those that contradicted his own. 8. Leadership Through Adversity: Aspiring to artistic expression, Lincoln's love for Shakespeare and theatricality significantly influenced his political style. While lacking military experience, he adeptly redefined the role of Commander-in-Chief, merging governance and military strategy during one of the nation’s most tumultuous periods. 9. Humor Amidst Tragedy: Lincoln’s humor, marked by self-deprecation and irony, served as a coping mechanism during the Civil War. His ability to laugh amid adversity, paralleling themes in Shakespearean tragedy, revealed an intrinsic understanding of the human condition. 10. Spiritual Complexity and Evolution: Questions about Lincoln’s religious beliefs emerge against a backdrop of historic interpretations. Though he never formally joined a church, his writings and observations hint at a profound spiritual journey, wrestling with the moral implications of the Civil War. 11. Public Engagement and Communication Skills: Skillful in manipulating public sentiment, Lincoln was an adept communicator who utilized the evolving media landscape. From public letters to the burgeoning telegraph, he shaped political discourse and audience perception, culminating in the poignant yet brief Gettysburg Address. 12. Redefining Conservatism: Lincoln’s thought evolved from a conservative view of preserving the founders' ideals to a belief in the necessity of progressive change. His assertion that prior dogmas were inadequate for contemporary challenges marked a shift towards a future-focused perspective, underlining his adaptability in thought. In summary, Lincoln’s legacy is a tapestry woven from the threads of personal integrity, moral introspection, and an impressive ability to communicate and connect with the American spirit. His life invites ongoing exploration, offering rich insights into both historical and contemporary dialogues about freedom, leadership, and the enduring quest for justice.

Key Point: Moral Integrity as Lincoln’s Foundation

Critical Interpretation: Consider the profound impact of moral integrity in your own life. Lincoln's unwavering commitment to his principles, despite immense pressure and adversity, serves as a compelling reminder that true leadership begins from within. Each decision you make, influenced by your own values, shapes not only your character but also the lives of those around you. As you navigate your own challenges, allow Lincoln's example to inspire you to stand firm in your beliefs, to reflect on what truly matters, and to confront difficult choices with honesty and courage. Embracing your ethical foundation can lead to a more purposeful existence and a legacy of integrity, much like the illustrious paths carved by great leaders throughout history.

Chapter 2 | Undistinguished Families 1809–16

In May 1860, Abraham Lincoln emerged as an unexpected nominee for the presidency of the Republican Party, elevating a relatively unknown attorney from Springfield, Illinois, to national prominence. The public's interest in his background surged, prompting journalistic inquiries into his past. As Lincoln contemplated the nation's future, journalist John Locke Scripps persuaded him to produce a brief autobiography, resulting in a three thousand-word essay that highlighted the limited nature of his formal education. Writing in a detached style, Lincoln stated that he had "picked up" the education he possessed, emphasizing his humble origins and the lack of emphasis he historically placed on his family background. 1. Despite public perceptions that Lincoln was indifferent to his ancestry, he was privately curious about it. As he approached the presidency, he sought to portray himself as a self-made man while also inquiring about his family lineage. While he noted that his parents came from "undistinguished families" in Virginia, the reality of his ancestry was more nuanced and historically rich than he recognized. Lincoln's direct paternal ancestor, Samuel Lincoln, immigrated to the New World in the early 17th century, embarking on a transformative journey that would lay the foundation for generations of Lincolns in America. 2. Samuel Lincoln's journey in April 1637 from England to New England was part of a larger movement known as the Great Migration. Motivated by political and religious upheaval in England, he sought the freedom to practice his faith and the promise of better economic opportunities in America. After landing in Salem, Massachusetts, Samuel settled in Hingham, where he became a prosperous farmer and community member, thus setting in motion the lineage that would lead to Abraham Lincoln. 3. The subsequent generations of Lincolns embraced the spirit of exploration and migration. Samuel's descendants, including Mordecai Lincoln and John Lincoln, moved further from their original homes in search of land and opportunity. Abraham Lincoln’s grandfather, also named Abraham, migrated to Kentucky, contributing to the pioneering legacy of the family. This migration pattern showcased the adventurous and pioneering American spirit, illustrating the family's embodiment of the era's values. 4. The lineage faced challenges, most notably the violent frontier life that Abraham's grandfather encountered. Captain Abraham Lincoln’s untimely death at the hands of a Native American attacker left his family in precarious circumstances, particularly impacting his young son, Thomas Lincoln. Nevertheless, Thomas averaged a successful life as a farmer and landowner despite losing his father early on. 5. Thomas Lincoln’s experiences on the frontier shaped his character and values. Often depicted unfavorably by history, a more nuanced perspective reveals a man who worked diligently to provide for his family, engaged in the community, and accumulated property. He married Nancy Hanks, who also faced significant early hardships. Together, they navigated the challenges of frontier life, creating a family that included a son named Abraham. 6. With Abraham Lincoln’s birth in 1809, his upbringing mirrored that of many frontier children. He experienced hardship and change as his family moved multiple times in pursuit of better opportunities, highlighting the trials of settlers and the evolving American landscape. Early on, Lincoln was exposed to various cultures and debates—particularly around slavery—which would later influence his political ideology. 7. The education Lincoln received was unstructured and sporadic, characterized by short stints at local subscription schools. Despite limited formal education, he gleaned knowledge through rigorous self-study and community networks. He developed a love for reading, often recalling his educational experiences with a sense of nostalgia for the basic yet profound learning he acquired. 8. The complex legacy of Lincoln’s family history reflects a tapestry of immigration, resourcefulness, and adaptability—a narrative that belies his own assessment of his ancestry as "undistinguished." From Samuel Lincoln’s pioneering spirit to the struggles and resilience of his immediate forebears, the qualities that Abraham valued in his own life—courage, perseverance, and moral conviction—were deeply rooted in the rich lineage from which he descended. Patterns of migration, community engagement, and exploration profoundly shaped the identity and worldview of Abraham Lincoln, leading him ultimately to become one of the most consequential figures in American history.

Chapter 3 | Persistent in Learning 1816–30

In his formative years in Indiana, Abraham Lincoln emerged as a unique figure, driven by an insatiable thirst for knowledge and personal growth. Arriving in Indiana at the age of seven after moving with his family from Kentucky in late 1816, Lincoln's youth was shaped by the dense wilderness, intellectual exploration, and challenging life experiences that would set the foundation for his later legacy. 1. Early Life and Physical Development: Growing up amidst Indiana’s unyielding landscape, Lincoln demonstrated remarkable physical growth, reaching six feet four inches by the age of twenty-one. His physicality was complemented by his ability to tackle the demands of frontier life, including clearing land and working on the family farm. At an early stage, Lincoln's aptitude for using an ax, a symbol of his emerging manhood, became significant both in his chores and as a part of his identity. 2. Literature and Intellectual Growth: Despite the harsh realities of frontier life, Lincoln fostered a love for reading. The limited educational opportunities in rural Indiana did not deter him; he voraciously consumed whatever books he could find, including classics such as Aesop’s Fables and the Bible. His reading cultivated a moral framework that influenced his character and future decisions. In fact, he began the habit of memorizing passages, solidifying the impact of literature on his intellectual and ethical development. 3. Family and Loss: Life took a tragic turn when Lincoln’s mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, died from "milk sickness" when he was just nine years old, an event that deeply affected him yet shaped his understanding of loss. His father's remarriage to Sarah Bush Johnston brought new stability and compassion to his life. Sarah’s influence proved pivotal; she encouraged Lincoln's education and provided a nurturing environment, fostering a bond that would significantly shape his upbringing. 4. Personal Responsibility and Work Ethic: By the age of ten, Lincoln began working for neighboring farms, which expanded his understanding of community and the variety of familial relationships. During this time, he honed crucial skills, such as rail splitting, which were in high demand in the burgeoning Midwest. As he earned money from his labor, he learned the value of hard work and the realities of economic independence. 5. Civic Engagement and Political Aspirations: Lincoln's interest in public affairs manifested as he began speaking at community gatherings, demonstrating an early knack for oratory and connecting with people. The community's political climate allowed him to explore a potential future in politics, where his ideas could find a broader platform. This blend of personal growth and civic responsibility marked Lincoln as a figure of great potential, ready to influence beyond mere survival. 6. Influence of Community and Experiences: Through interactions with neighbors, traders, and experiences on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, Lincoln gained insights into diverse social and economic systems. His trip to New Orleans at the age of nineteen exposed him to the stark realities of slavery, embedding a sense of social justice that would later define his political career. 7. Transition to Illinois: In 1830, after multiple relocations, Thomas Lincoln moved the family to Illinois on the cusp of a new chapter in Abraham's life. Leaving Indiana, young Lincoln faced an opportunity for self-discovery. He took an active role in establishing a new home while seeking paths for further education and community engagement, ultimately reflecting the desires and struggles of many young men of his era. Lincoln's early experiences in Indiana formed the bedrock of his values, work ethic, and inspirational leadership style. His struggles, personal losses, and pursuits for knowledge not only defined him but laid intricate pathways for his future contributions to American society. Each step of his tumultuous youth in frontier America provided a frame of reference that would guide him in navigating the complexities of a rapidly changing nation.

Chapter 4 | Rendering Myself Worthy of Their Esteem 1831–34

On a blustery day in April 1831, the village of New Salem, Illinois, witnessed a pivotal moment as Abraham Lincoln, then a tall but inexperienced young man, struggled to help free a stranded flatboat carrying goods. This incident marked the beginning of Lincoln's relationship with the community as he endeavored to distance himself from his past, particularly his father's farming legacy, and explore new ambitions. 1. Transition to New Salem: Following his journey to New Orleans to pilot the flatboat, Lincoln returned to New Salem, where he sought to carve out a new life. At twenty-two and recognizing the formative nature of this time, he accepted a job in a grocery store, which was a step toward gaining the respect and esteem he deeply desired from his peers. His commitment to personal growth and social standing led him to view his time in New Salem as critical for his development. 2. Community Engagement: New Salem, established around 1829, was a burgeoning settlement that relied on the Sangamon River for transportation and commerce. Lincoln's engagement with the community grew as he navigated local politics and economics while connecting with the region’s hopes of becoming a prosperous river town. The village lacked formal religious structures yet was vibrant with diverse spiritual gatherings, indicating a community in search of identity and unity. 3. Political Aspirations: Lincoln's initial foray into politics came during an election when he voted for the first time and later announced his candidacy for the Illinois state legislature. His election announcement revealed his ambitious nature, emphasizing his desire to be esteemed while illustrating his humble origins. He spoke candidly about his background and eagerness to earn the community's respect through hard work and dedicated service. 4. Military Experience: The onset of the Black Hawk War interrupted his political ambitions, but it also solidified his leadership credentials as he became captain of his militia unit. Lincoln's calm demeanor in the face of conflict and his ability to uphold discipline within his ranks showcased a nascent leadership quality that would define his future. 5. Literary and Intellectual Growth: While living in New Salem, Lincoln's intellectual curiosity flourished. He joined a local debating society which allowed him to hone his oratory skills, immerse himself in discourse, and engage with Enlightenment thinkers. His reading habits broadened significantly, challenging his previous religious beliefs and deepening his critical thinking. 6. Professional Ventures: After a failed partnership in a local store, Lincoln sought other avenues of income, eventually becoming New Salem's postmaster, which offered him both financial stability and an opportunity to engage more robustly with local and national politics through the consumption of newspapers. His subsequent role as a surveyor enabled him to build further connections with the growing community, amplifying his reputation and political network. 7. Second Political Campaign and Victory: In 1834, having gained more recognition and support from the community through various jobs and his active campaigning approach, Lincoln ran for the state legislature again. His ability to connect with voters through a blend of policy discussions and personal engagement paid off, as he secured a significant electoral victory that marked the beginning of a more formalized political career. Overall, Lincoln's formative years in New Salem were characterized by a series of transitions—from a struggling young man seeking respect to an emerging political leader. His journey was shaped by his interactions with the community, his military service, and an invigorating pursuit of knowledge that laid the groundwork for his future endeavors and political philosophies. As he defined his identity and ambitions in this formative period, he began to embrace a vision of public service intertwined with personal integrity, which would guide him throughout his life.

Chapter 5 | The Whole People of Sangamon 1834–37

On the morning of November 28, 1834, Abraham Lincoln embarked on a pivotal journey to Vandalia, Illinois, eager to assume his role in the Ninth General Assembly. Having come a long way in over three years since his arrival in New Salem, Lincoln demonstrated his determination and ambition as he prepared for the legislative session. Before leaving, he secured a loan from a friend for suitable clothing, highlighting his desire to present himself well. 1. Lincoln’s Arrival: The young Lincoln, then twenty-five and relatively unknown, arrived in Vandalia, the state's second capital, which had developed from a small frontier settlement into a bustling hub for legislators. The legislature operated in a modest two-story capitol that often interrupted deliberations with falling plaster and sagging floors, emblematic of the struggles in the early 19th century legislative process. 2. Initial Participation: Upon his arrival, Lincoln was a newcomer among seasoned representatives, many of whom were experienced lawyers. However, he dutifully attended sessions, learned the legislative ropes, and found his voice in the assembly. Notably, he introduced a bill concerning Justices of the Peace, though it became bogged down in procedural complexities. 3. Rising Influence: As the session progressed, Lincoln gained recognition for his wit and insight. He adeptly navigated parliamentary procedures, famously humorously suggesting the legislative body allow the continuation of an incumbent surveyor while maintaining a support system for potential vacancies. Such moments endeared him to colleagues, leading to appointments on several special committees and opportunities to speak on significant motions, an indication of his growing influence. 4. Financial Hardship: Despite his progress, Lincoln returned home burdened by a financial ordeal stemming from his past partnership in a failed general store. Departing from common expectations for debtors in the frontier life, he chose to honor his commitments, establishing his reputation as "Honest Abe." This resolve earned him respect within his community even amidst financial tribulations. 5. Legal Aspirations: Encouraged by allies, Lincoln began exploring the legal field seriously, taking steps towards formal law practice. With no law schools available in Illinois, he pursued a self-directed study using guidance from prominent local attorneys, which laid the foundation for his future legal career. 6. Reelection Campaign: With renewed commitment, Lincoln announced his candidacy for reelection in March 1836, articulating a philosophy that emphasized serving the will of all constituents amid changing political tides marked by the recently established Democratic leadership of Martin Van Buren. 7. Legislative Accomplishments: Lincoln's second term brought new responsibilities, including a leadership role as floor leader for the Whigs. He aligned himself with peers advocating for infrastructure improvements, championing proposals for major public works investments critical for the state's development amidst economic growth scenarios. 8. Relocation of the Capital: Lincoln played a crucial role in persuading fellow legislators to relocate the state capital to Springfield, a strategic move that would enhance his influence. Celebrating this success, he exhibited unwavering resolve throughout the contentious legislative process. 9. Engaging with Abolitionism: An important chapter in Lincoln's political stance occurred when he courageously opposed a resolution to denounce abolitionist movements, signifying his first public stand against slavery. Together with a colleague, he framed a protest that acknowledged the powers of Congress while emphasizing a nuanced approach to the complex issue of slavery in the nation. 10. Transition to Springfield: By the close of the legislative session in March 1837, Lincoln had transitioned into a figure equipped with political and legal credentials, ready to navigate the complexities of his evolving career. With New Salem in decline, he moved to Springfield, where he would solidify his role as a prominent lawyer and politician. In summary, Lincoln's formative years in the Illinois legislature shaped his values, honed his talents, and rooted his public persona as he embarked on a lifelong commitment to public service and the pursuit of justice.

Key Point: Embrace Financial Responsibility

Critical Interpretation: Lincoln's unwavering commitment to honor his debts, despite personal financial struggles, serves as a powerful reminder that integrity and responsibility are fundamental to our character. In your own life, when faced with challenges, let Lincoln's example inspire you to confront difficulties head-on and adhere to your values. By doing so, you not only build trust within your community but also foster a personal environment where accountability and resilience become your driving forces.

Chapter 6 | Without Contemplating Consequences 1837–42

In April 1837, Abraham Lincoln arrived in Springfield, Illinois, with hope and uncertainty. He borrowed a horse for the journey, carrying only his modest belongings, and dismounted in front of Abner Ellis's general store. It was here that Lincoln met Joshua F. Speed, the store's proprietor, who recognized Lincoln's reputation as an emerging politician. Unable to pay for basic furniture due to his financial struggles, Lincoln was welcomed by Speed into his home, an act showcasing their developing friendship. Springfield during Lincoln's arrival was a burgeoning town, characterized by its humble beginnings with a population of around 1,300. It featured a mix of small homes and log cabins, and when the town was chosen as the capital of Illinois, excitement and hope for future development filled the air. Lincoln's journey into legal practice began shortly after he received his license as a lawyer, which, while significant, brought alarm, considering the number of established lawyers in the area. Lincoln’s first stroke of luck came when John Todd Stuart offered him a partnership, allowing Lincoln to work alongside one of Springfield's leading lawyers at a time when the financial crash of 1837 was disrupting lives. With limited resources, Lincoln took on a variety of cases, displaying a knack for building rapport with juries, especially during his first criminal trial, which he successfully argued, enhancing his reputation. As Lincoln's skills evolved, so did his responsibilities within the law office. He became known not only for drafting legal documents with clarity but also for managing financial records, where he faced challenges with organization. Despite this, his legal acumen grew as he took on a wide array of case types. When Stuart left for Congress, Lincoln was thrust into a position that required him to operate independently, allowing his legal practice to flourish as he gained confidence. Throughout this time, Lincoln furthered his political ambitions, participating in debates and representing the Whig party’s ideals by advocating for internal improvements, despite the economic downturn. His speeches showcased his eloquence and passion for governing principles rooted in advancing society through infrastructure and economic stability. Lincoln’s social life evolved as well, particularly his friendship with Joshua Speed, which provided a bridge into Springfield’s social circles. Speed helped Lincoln overcome his shyness, drawing him into gatherings that featured vibrant discussions and camaraderie among like-minded individuals. Lincoln’s personality shone in these groups, revealing a man who, while reserved, possessed a deeply engaging sense of humor. In his drive for self-improvement, Lincoln recognized the importance of public speaking and sought opportunities to address local organizations. His temperance address in 1842 illustrated a key turning point in his oratory skills. He critiqued existing temperance methods, advocating for a compassionate approach that emphasized understanding and friendship rather than condemnation. As Lincoln's public stature grew through his legislative work and debates, he also faced challenges, including a contentious 1840 presidential campaign for the Whigs, where economic issues remained a focal point. Despite not winning the presidential election for Whig candidate William Henry Harrison in Illinois, Lincoln emerged as a prominent figure in State politics. Despite the success he achieved in his public life, Lincoln battled insecurities in his personal life. His journey from a political novice to an influential lawyer and politician encompassed triumphs and struggles, foreshadowing the significant role he would come to play in American history as both a leader and a reformer. 1. Arrival in Springfield: Lincoln's transition from New Salem to Springfield marked a significant turning point in his life as he navigated new beginnings filled with uncertainty. 2. Relationship with Joshua Speed: Their significant friendship offered support that allowed Lincoln to engage more with society and overcome his reservations. 3. Legal Career Beginnings: Lincoln's partnership with Stuart signified his first step into law, where he faced early financial challenges but gained success through effective jury persuasion. 4. Evolving Political Aspiration: Throughout the late 1830s to early 1840s, Lincoln advocated for internal improvements while cultivating his reputation as a skilled orator within the Whig Party. 5. Public Speaking Evolution: His temperance address revealed Lincoln's growth in public discourse, focusing on persuasive and compassionate communication, highlighting his understanding of human nature. 6. Political Engagement and Emergence: Lincoln's work in legislative sessions and campaign involvement showcased his increasing political prominence, setting the stage for his future leadership role. 7. Balancing Personal Insecurities: Despite public successes, Lincoln's personal life remained a source of anxious reflection as he sought to find companionship and belonging.

Chapter 7 | A Matter of Profound Wonder 1831–42

In Chapter 7 of "A. Lincoln" by Ronald C. White Jr., an exploration of Abraham Lincoln's emotional landscape unfolds, detailing his early romantic relationships and the profound impact they had on his life. This chapter addresses several significant themes, characterized by the following principles: 1. Emotional Turmoil: Lincoln's correspondence reveals a deep emotional struggle. In a letter to John Todd Stuart, he proclaims, “I am now the most miserable man living,” expressing a sense of despair that would resonate throughout his life. This sentiment echoes his experiences of loss, having lost his mother and sister, and later, his first love, Ann Rutledge, to untimely death. 2. Awkwardness and Shyness: Initially, Lincoln displayed a notable awkwardness, particularly with young women. His shyness was evident during his courtship of Ann Rutledge and later with Mary Owens. However, he found acceptance and encouragement from older women in New Salem, who often mothered him and guided him in matters of the heart. These relationships provided him with a form of emotional support amidst his insecurities. 3. The Impact of First Love: Lincoln's bond with Ann Rutledge represented his first meaningful romantic connection. Although deeply in love, their courtship was fraught with challenges, including Ann’s engagement to another man. Tragically, Ann's death in 1835 devastated Lincoln, throwing him into profound mourning and leaving him emotionally scarred, which would affect his subsequent relationships. 4. Transition to Maturity: After Ann’s death, Lincoln's relationship with Mary Owens signified a shift toward courting a more mature woman. Their connection was marked by comic misunderstandings and Lincoln's deeply rooted insecurities. The courtship was filled with doubts about their compatibility, reflective of Lincoln's struggles with self-esteem and his fear of being deemed unsuitable as a husband. 5. Rekindled Romance: Despite an initial estrangement from Mary Owens, Lincoln's relationship took a turn following a mutual desire to reconnect. Their rendezvous initiated a gradual process of reconciling emotions, culminating in Lincoln’s struggle to determine if he should marry. 6. Marriage to Mary Todd: The relationship progressed, setting the stage for Lincoln to marry Mary Todd. Their courtship, however, was punctuated by societal pressures and familial objections. Mary’s educational background and social standing contrasted sharply with Lincoln’s humble origins. Their eventual marriage, hastily arranged after a series of significant challenges, reflected both their personal and familial complexities. 7. Commitment and Balance: Lincoln’s marriage presented a new chapter where he sought to strike a balance between his emerging political career, legal aspirations, and family life. This new commitment of marriage became a crucial pillar in his journey to fulfilling professional ambitions. His wedding ring, inscribed with “Love is Eternal,” epitomized his intent to cultivate a lifelong dedication to Mary. In summation, this chapter intricately weaves together Lincoln's complex emotional world as he navigated love, loss, and the eventual embrace of marriage. These early romantic experiences would mold Lincoln's character and influence his later relationships, shaping the man who would ultimately rise to prominence in American history.

Chapter 8 | The Truth Is, I Would Like to Go Very Much 1843–46

At the beginning of 1843, Abraham Lincoln received a significant opportunity to pursue a larger political role when his former law partner, John Todd Stuart, announced he would not run for a third term in Congress. Lincoln, who had previously declined a fifth term in the state legislature, quickly positioned himself as a candidate for the newly created Seventh Congressional District in Illinois. The district, covering eleven counties primarily populated by residents from Sangamon County, had a competitive field for the Whig nomination, particularly among three young lawyers: John J. Hardin, Edward D. Baker, and Lincoln himself. As Lincoln launched his campaign, he was conscious of the electoral environment; Illinois had expanded from one congressional seat at its statehood in 1818 to seven by 1843 due to rapid population growth. The Whigs believed they could secure a victory in this new district. In crafting his strategy, Lincoln proactively reached out to supporters and penned a Whig address that emphasized party unity and the need for their collaborative political action. He recognized the power of a convention system for nominations, which could bolster the Whigs' chances against the Democrats who had successfully adopted this method. However, Lincoln faced challenges during the nomination race. Critics portrayed him as an ally of the wealth and privilege due to his marriage to Mary Todd, intertwining him with elite circles. Additionally, his lack of formal church membership attracted scrutiny, especially as his opponent, Baker, enjoyed a strong religious backing as a lay minister. This tension regarding religion and class positioned Lincoln as an outsider within the very party he sought to lead. During the nomination convention in March 1843, Baker initially led in ballots, and despite Lincoln's efforts, he was asked to withdraw for party unity. Embracing the spirit of collaboration, Lincoln accepted a leadership role supporting Baker over Hardin, proposing a rotation system which would later allow him a pathway to future nominations. Though he lost the primary, he maintained goodwill among the Whigs and kept his political ambitions alive. In 1844, as Lincoln focused on establishing his law practice with a new partner, William Herndon, he actively engaged in the national political climate which saw him campaign for Henry Clay against Democrat James K. Polk. This election was crucial as it involved key themes of slavery and territorial expansion. Lincoln's disappointment in the election loss highlighted the necessity for cautious political alignment to avoid alienating potential allies in the evolving anti-slavery movement. By the autumn of 1845, with strong political maneuvers, Lincoln positioned himself to seek the Whig nomination once more amidst speculation that Hardin might challenge him again. In clarifying his intent, Lincoln framed his candidacy around the principle of fairness, suggesting that political turn-taking was a rightful strategy among their circle. He utilized calculated tactics, including direct correspondence with key delegates to support his nomination. Lincoln’s campaign culminated with his acceptance into the congressional race in May 1846 amidst the backdrop of the Mexican-American War, boosting national sentiment for military service. As he faced off against prominent preacher and politician Peter Cartwright, Lincoln endeavored to counter religiously charged accusations that aimed to undermine his candidacy based on his non-sectarian beliefs. Ultimately, Lincoln's broad support led to an electoral victory, securing 6,340 votes in August 1846, marking a significant achievement in his political ascent. However, he experienced a delay in taking office, allowing him time to attend significant political gatherings such as the Rivers and Harbors Convention, where he made an impactful speech that garnered further recognition. As he transitioned from a hopeful candidate to an elected congressman, Lincoln’s early experiences of political contestation reflected pivotal moments that shaped his future leadership. His connections, skills in persuasion, and evolving approach to party dynamics would influence his trajectory in both Congress and the wider political landscape of an increasingly divided nation.

Chapter 9 | My Best Impression of the Truth 1847–49

In Chapter 9 of "A. Lincoln" by Ronald C. White Jr., Abraham Lincoln's journey from Springfield, Illinois to Washington D.C. unfolds, interwoven with personal and political events that shape his early political career. As he and his wife Mary prepare to leave their home in Springfield, they embark on a six-week journey filled with familial reconnections, particularly with Mary’s family in Lexington, Kentucky. During this visit, Lincoln witnesses the realities of slavery, which profoundly impact his views. 1. Recognition of Slavery: In Lexington, Lincoln observes the common practices of slavery, evident in both the Todd household and local newspapers featuring advertisements for the sale of enslaved people. This experience reignites Lincoln's awareness of slavery's moral implications, setting the stage for his future abolitionist sentiments. 2. Influence of Political Figures: While in Kentucky, Lincoln attends a political meeting featuring Henry Clay, a revered figure whose ideas shaped Lincoln's political beliefs. Clay’s fiery opposition to the Mexican-American War resonates with Lincoln, who, upon arriving in Congress, grapples with the complexities of war, governance, and morality. 3. The Thirtieth Congress: Lincoln arrives in Washington D.C. with enthusiasm, ready to immerse himself in legislative debate. He is struck by the city’s nascent status and is overwhelmed by the dynamics of the Capitol, where newer and younger members like himself are about to make their mark. Lincoln’s seat assignment places him among influential figures who will shape national discussions, particularly regarding slavery and the ongoing war. 4. Emergence of Political Thought: Lincoln’s early days in Congress unveil his commitment to articulate his stance on pressing issues, including the justification of the Mexican War. His resolutions, famously termed the "spotty" resolutions, challenge President Polk's claims that Mexico initiated the conflict. This confrontation propels Lincoln into the political spotlight, demonstrating his willingness to question authority. 5. Public Response and Political Consequences: Lincoln’s critiques of the war and Polk lead to mixed reactions back home. Despite Lincoln’s efforts to clarify his support for the troops while opposing the war’s rationale, he faces backlash and perceptions of treachery from constituents who misconstrue his stance. This push-pull between local expectations and national political context reveals the challenges faced by newly elected officials. 6. Lincoln’s Rhetorical Growth: Throughout the chapters, Lincoln’s skills as a speaker evolve, particularly during a speech addressing a rally in Massachusetts. His ability to integrate humor and self-deprecation into his rhetoric helps him connect with diverse audiences while promoting Whig principles. 7. Family and Personal Life: Amid the political landscape, Lincoln’s correspondence with Mary reflects both the affection and strains in their marriage. Their letters convey longing and serve as a window into Lincoln’s personal sacrifices as he navigates the complexities of political service away from home. 8. Political Setbacks and Reassessments: After returning to Springfield post-congressional session, Lincoln grapples with the political landscape and criticism of his congressional actions, which leads him to reconsider his political future. Under increased scrutiny and internal party challenges, Lincoln ultimately decides to focus on his legal career, distancing himself from a political arena that seems increasingly hostile. 9. Enduring Legacy: The chapter encapsulates not only Lincoln’s political awakening but also the contradictions of his public service. It highlights a formative period essential for understanding his later decisions and moral clarity regarding slavery, governance, and national identity. Through detailed anecdotes and observations, this chapter delineates the emerging complexities of Lincoln’s political philosophy while concurrently unveiling the personal dimensions that shape his character and future leadership during a turbulent era in American history.

Chapter 10 | As a Peacemaker the Lawyer Has a Superior Opportunity 1849–52

In the spring of 1849, Abraham Lincoln returned to Illinois after his single term in Congress, which had been marked by his unpopular opposition to the Mexican War. With no political position to occupy, he resumed his law practice, hoping to bolster his legal career to provide better for his family. Although he had an opportunity for a partnership in Chicago, he opted to remain in Springfield, preferring the local legal community over the pressures of a lucrative position. His return to law marked a time of dedicated practice, where he pursued self-education and intellectual growth. 1. Legal Philosophy and Practice: Lincoln saw law not merely as a profession but as a means to improve society. Acknowledging the significant changes in legal practice since he began, he adapted to more formal standards and complex precedents. He believed that diligence was the essential rule for any lawyer, advising that no tasks should be left undone. Furthermore, he considered public speaking a vital skill for lawyers, emphasizing the importance of being able to communicate effectively. 2. Role as a Mediator: Central to Lincoln’s approach was the concept of discouraging litigation. He recognized that many disputes could be resolved through compromise rather than conflict. This mindset became evident in his dealings with clients, such as Abram Bale in a case involving a financial dispute over flour, where Lincoln encouraged settlement over prolonged litigation. His homegrown mediation skills helped him to better understand the dynamics at play within small communities. 3. Intellectual Engagement: While practicing law, Lincoln remained committed to self-education. He read widely, including legal texts, literature, and newspapers, to form a comprehensive understanding of contemporary issues, including conflicting views on slavery. His pursuit of knowledge extended into late-night study sessions, which he undertook despite the demands of his legal career. 4. Political Landscape and Compromise: During this period, Lincoln closely followed national events, specifically the Compromise of 1850 orchestrated by Senator Henry Clay. This series of measures was designed to alleviate the tensions between North and South over the issue of slavery, aiming for a balanced resolution. Lincoln viewed these compromises as temporary fixes that did not fully address the underlying issues. 5. Personal Struggles and Family Life: Amidst his growing legal responsibilities, Lincoln faced profound personal challenges, including the tragic death of his son Eddie, which deeply affected both him and his wife Mary. The loss added strain to their already difficult marriage, marked by Lincoln's frequent absences due to work. Mary’s struggles with feelings of abandonment led her to focus intensely on their surviving children. 6. Shift Towards Faith: In the aftermath of personal losses, Lincoln also began to engage more with religious thought, prompted in part by his interactions with Reverend James Smith. His burgeoning interest in a rational Christianity reflected a deeper search for meaning in his life. 7. Professional Growth and Reputation: Lincoln’s reputation as a lawyer grew steadily as he traveled the Eighth Judicial Circuit, where he reconnected with old friends and established new relationships, including his collaboration with Judge David Davis and lawyer Leonard Swett. This circle, dubbed the “great triumvirate,” became noted for their camaraderie and influence in both legal and political realms. 8. Legacy of Leadership and Vision: Reflecting on the leadership of figures like Henry Clay, Lincoln articulated his belief that wise governance required a blend of tradition and innovation. He understood the importance of adapting and defining the ideals of America to resonate with changing times, foreshadowing his own impending return to the political arena. Through thoughtful reflection, persistent legal practice, and a commitment to principles of mediation and compromise, Lincoln forged a path that would not only enhance his career but eventually lead him back into the political spotlight, setting the stage for his prominent role in shaping the nation's future.

Chapter 11 | Let No One Be Deceived 1852–56

In Chapter 11 of Ronald C. White Jr.'s "A. Lincoln," the narrative delves into the profound transformation of Abraham Lincoln's political identity during the tumultuous period surrounding the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Shocked by the passage of this legislation, which allowed settlers in those territories to decide the fate of slavery, Lincoln grappled with the implications on America's foundational principles of liberty and equality. 1. Political Awakening: After initially feeling unprepared for the political upheaval, Lincoln began sharpening his rhetoric and deepening his understanding of the national debate surrounding slavery. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, introduced by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, aimed to settle Westward expansion issues but instead intensified conflict by undermining previous compromises regarding slavery. 2. A Shifting Political Landscape: The political dynamics shifted dramatically as the Whig Party faltered and antislavery sentiments swelled. Lincoln emerged from relative political obscurity, bolstered by a newfound sense of purpose and the realization that he must actively engage in the escalating conflict over slavery. 3. Public Discourse: Lincoln carefully analyzed speeches and political positions as he developed his own arguments against the extension of slavery. Notably, his discussions with other prominent abolitionists and his observations of the emerging Republican Party highlighted his evolving stance. While he remained committed to the Whig Party at first, the political climate—exacerbated by growing nativism and radical abolitionists—compelled him to reassess his allegiance. 4. Moral Clarity: The chapter showcases Lincoln's moral reflections on slavery, revealing his deep conviction that the institution was contrary to the nation’s founding ideals. His writings during this time reflect a growing urgency for moral clarity and justice, which would become hallmarks of his later political speeches. 5. Developing Leadership: By the summer of 1854, Lincoln began to publicly articulate his opposition to slavery. His speeches at different gatherings, particularly to German immigrants who were straying from traditional party lines, underscored his principle of empathy toward all citizens, regardless of their stance on slavery. He positioned himself as a moderate voice amid rising tensions, advocating for unity and understanding. 6. The Birth of the Republican Party: The 1856 state convention in Bloomington marked a pivotal point in Lincoln's political journey. Rising to prominence, he expressed a vision that transcended partisanship, advocating for a collective anti-slavery approach. Here, his powerful rhetoric gained traction, positioning him as a leading figure in the burgeoning Republican Party. 7. Philosophical Realizations: Throughout this chapter, Lincoln's deeper understanding of human rights and liberty evolves. He contemplated the moral contradictions in society, highlighting the pervasive hypocrisy surrounding the nation’s self-image versus its realities. His reflections did more than demonstrate personal growth; they also laid out a national vision grounded in the foundational ideals of the Declaration of Independence. 8. Legacy in Reflection: By the end of the chapter, Lincoln’s retreat from a direct pursuit of political office reflects a broader strategic vision. His insights into the future of the nation indicated that he was ready to lead a movement rather than merely hold a position. Lincoln’s journey from political exile to a clarion voice for liberty illustrates the maturation of his character and thought processes, preparing him for the tumultuous years that would follow. In summary, Chapter 11 of "A. Lincoln" profoundly captures the momentous shifts occurring in both Lincoln's political ideology and the broader American socio-political landscape as the nation grappled with its moral crisis over slavery, all while setting the stage for Lincoln's future leadership during one of the most critical eras in American history.

Chapter 12 | A House Divided 1856–58

In June 1856, Abraham Lincoln found himself unexpectedly in the spotlight as the Republican Party's influence began to grow. On the morning of June 20, the election results announced that Lincoln had garnered substantial support at the Republican National Convention, marking his rise as a national figure despite his initial reluctance to embrace the party. The delegates nominated military hero John C. Frémont as the first presidential candidate, with Lincoln receiving notable votes for vice president. 1. Lincoln's Early Political Engagement Lincoln, motivated by his newfound national standing, threw himself into campaigning for Frémont. He contrasted the Democratic candidate, James Buchanan, who was politically seasoned but viewed as tainted, with Frémont, whose celebrity status appealed to the electorate. Lincoln traveled extensively, speaking out against slavery and emphasizing that the 1856 campaign centered on the fundamental question of freedom versus slavery. 2. Concept of Sectionalism Amid his campaigning, Lincoln engaged in private contemplation about sectionalism, acknowledging fears surrounding the Republican Party's image as a sectional, anti-slavery entity. His reflections lead to a commitment to articulate the party's stance as one of national unity rather than division. 3. The 1856 Presidential Election Despite a vigorous campaign, Frémont lost to Buchanan, who did not achieve a popular vote majority. However, the election showcased the growing strength of the Republicans in the North and foreshadowed future political contests. Lincoln emerged as a leader within the party, recognized for helping secure victories at the state level despite Frémont’s defeat. 4. The Dred Scott Decision In December 1856, the Supreme Court's decision in the Dred Scott case ruled that African Americans could not be citizens and that Congress could not prohibit slavery in the territories. This decision sparked outrage among Republicans and intensified the national debate over slavery. While Lincoln refrained from immediate public commentary, he began preparing to contest the implications of the ruling. 5. Lincoln's Meticulous Preparation As he laid the groundwork for his campaign for a Senate seat in 1858, Lincoln dedicated himself to carefully crafting his speeches, including his famous "House Divided" address. This speech, delivered at the Republican convention in Springfield, conveyed his belief that the nation could not endure half slave and half free. He asserted the inevitability of a resolution to the issue of slavery, foreshadowing a national crisis. 6. The "House Divided" Speech On June 16, 1858, Lincoln delivered his "House Divided" speech, stating his conviction that the current division over slavery could not be sustained. He employed biblical metaphors and rhetorical strategies to argue that the nation must ultimately choose a path—either to restrict slavery's expansion or to accept its proliferation. The speech positioned him as a clear voice against the prevailing pro-slavery interests. 7. Emergence as a National Leader Lincoln's rhetoric and arguments not only solidified his candidacy for the Senate but also marked a pivotal moment in his political trajectory. He adeptly connected personal reflections with larger national concerns, illustrating his ability to articulate the moral imperative of ending slavery. Throughout this chapter, Lincoln's evolving public persona as a leader is highlighted alongside the turbulent political backdrop of the 1850s, underscoring his growing commitment to the anti-slavery cause and the preservation of the Union. As he recursively links personal anecdotes and broader political themes, the foundation for Lincoln's future presidency begins to take shape.

Key Point: The importance of standing firm for one's beliefs in the face of adversity.

Critical Interpretation: As you reflect on Lincoln's commitment to speak against slavery and advocate for national unity despite challenges, consider how this tenacity can inspire you in your own life. Just as Lincoln stepped into the political arena when it was fraught with challenges, you are encouraged to stand firm in your beliefs and values, even when confronted with opposition. This chapter’s lesson reveals that true leaders are forged not in times of ease, but in the crucible of adversity. By embodying Lincoln’s courage, you can recognize the power of your voice in shaping the world around you, advocating for justice and change, no matter the obstacles you may face.

Chapter 13 | The Eternal Struggle Between These Two Principles 1858

In 1858, Abraham Lincoln embarked on a significant campaign against Stephen A. Douglas for the U.S. Senate seat in Illinois. Their rivalry became the backdrop for a larger national debate over slavery and equality, heightened by Lincoln's bold "House Divided" speech, which resonated deeply within the social and political climate of the time. 1. Initial Reactions and Defensive Stance: Following Lincoln's renowned "House Divided" speech, both admirers and critics were taken aback; while it earned him praise for its eloquence, some perceived it as radical. Notably, John Locke Scripps, a Chicago editor, expressed concern that Lincoln's words could suggest an aggressive stance against slavery. In response, Lincoln clarified that he did not advocate for federal intervention in states where slavery already existed, but instead predicted its gradual decline. 2. Douglas’s Campaign and Lincoln’s Strategy: Stephen Douglas, recognizing Lincoln’s strengths as a formidable opponent, confidently described him as a “strong man” filled with wit and facts. Douglas's campaign launch was met with public enthusiasm, where he defended his political principles while subtly undermining Lincoln. As the campaign progressed, Lincoln adapted his strategy by challenging Douglas to a series of debates that would unfold across Illinois, believing this approach would provide him a platform to directly confront Douglas's positions. 3. Engagement Through Debates: The Lincoln-Douglas debates, stemming from Lincoln’s challenge to Douglas, became central to the campaign and showcased both men's ideological clashes. The first debate in Ottawa drew a massive crowd and spotlighted their contrasting views on slavery. Lincoln, while focusing on human equality as enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, sought to highlight the moral implications of slavery. In contrast, Douglas emphasized popular sovereignty, arguing for the right of states to decide on slavery without federal interference, often appealing to the prejudices of his audience. 4. Shift in Momentum: Over the course of the debates, Lincoln honed his public speaking skills and strategically seized the moral high ground. By engaging directly with Douglas’s arguments and employing humor to connect with the audience, he gained momentum. His performance in the later debates, particularly at Galesburg and Quincy, marked a notable shift where he articulated a more compelling moral critique of slavery that resonated with many voters. 5. Reactions and Outcomes: As the debates concluded, public opinion in Illinois reflected the fluctuating dynamics of the campaign. Despite a vigorous effort that drew thousands to each debate, the election culminated in a narrow defeat for Lincoln. However, the campaign established him as a national figure and laid the groundwork for future political endeavors. Lincoln's observations about the deeper moral question of slavery gained traction beyond Illinois and would come to characterize his legacy. 6. Reflection on Defeat and Future Aspirations: In the aftermath of the election, Lincoln exhibited remarkable resilience, viewing his participation as a means to advance national conversations around civil rights and liberty. His reflections underscored a recognition that the struggle for equality transcended individual political ambitions. Lincoln's ability to articulate a principled stance against slavery solidified his place in history, opening pathways for his subsequent rise to the presidency. Through these debates and campaign activities, Lincoln not only confronted Douglas's arguments but also grappled with the broader national challenges of slavery and equality, endearing himself to the public and fostering a deeper discourse on issues that would shape the nation’s future. The debates, marked by intense public interest and competing narratives, became more than just a contest for a Senate seat; they were pivotal moments in the struggle for civil rights and the redefinition of American identity in the face of moral and ethical dilemmas.

Chapter 14 | The Taste Is in My Mouth, a Little 1858–60

In Chapter 14 of "A. Lincoln" by Ronald C. White Jr., the narrative unfolds against the backdrop of Abraham Lincoln’s evolving political trajectory leading up to his nomination for the presidency in 1860. The chapter encapsulates key events and sentiments that shaped public perception of Lincoln, highlighting his journey from a relatively obscure Illinois politician to a serious contender for the Republican nomination amid the tumult of the era. 1. Following Lincoln's Senate defeat in 1858, local newspapers began advocating for him to seek the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. Editors and citizens recognized his potential to unify the party and the nation through his integrity and political acumen. The calls for Lincoln’s candidacy grew from small, regional publishers to more prominent publications, indicating a shift in how he was viewed nationally. 2. Jesse Fell, a long-time acquaintance of Lincoln, played a crucial role in shaping his presidential aspirations. After advocating for Lincoln's broader recognition outside of Illinois, Fell urged him to publish an autobiographical statement. Although Lincoln initially dismissed the idea, he quietly worked on a scrapbook of his debates, indicating an underlying ambition that he was reluctant to articulate directly. 3. Lincoln’s career was challenged as he attempted to balance his law practice with political concerns, a struggle made harder by the financial toll of the Senate campaign. His interactions with clients demonstrated his disappointment and impatience with the political game while still seeking to stay politically active. 4. By the early months of 1859, Lincoln became a leading figure in Illinois politics amidst speculation about the Republican convention and potential candidates for the presidency. However, he remained cautious about his own prospects, often expressing doubt regarding his qualifications compared to established names like Seward and Chase. His reluctance showcased his modesty but also a keen awareness of the political landscape. 5. As he became involved in national discussions, Lincoln offered insights into maintaining Republican unity and managing divisive issues like the Fugitive Slave Act. He emphasized the importance of presenting a consistent and united front leading up to the crucial elections of 1860. 6. Lincoln's speaking engagements expanded significantly in 1859, marking a transition from a local to a national leader. His public speeches distinguished him from other candidates, revealing his growing oratorical skill and the ability to appeal to various audiences. His famous Cooper Union address in New York exemplified this transition, as he adeptly countered counterarguments while establishing himself as a leading candidate. 7. The pivotal moment in Lincoln's political ascent came with his Cooper Union speech, which served as a clarion call against the extension of slavery and showcased his historical knowledge and moral commitment. The overwhelmingly positive reception further ignited interest in his candidacy, prompting a swift rise in media endorsements. 8. The convention season approached, and as the prospect of a presidential nomination loomed, Lincoln's name began to attract serious consideration. Despite doubt and modesty, he gradually accepted his burgeoning influence and the potential for nominating him as the Republican standard-bearer. 9. By the time of the Republican convention in Chicago, Lincoln benefitted from a network of supporters and strategic campaigning. His advisors, particularly David Davis, played critical roles in coordinating efforts to gather support from various state delegations, emphasizing Lincoln's moderate stance as a counterpoint to other leading candidates. 10. The complexities of the convention dynamics are highlighted as Lincoln faced stiff competition from well-known figures like Seward and Bates. However, as voting progressed, a remarkable shift occurred with Lincoln gaining unexpected support from states that had initially favored other candidates, ultimately leading to his historic nomination as the Republican candidate for president. Through detailed narratives, Chapter 14 vividly illustrates Lincoln's political evolution, the challenges he faced, and the strategic responses that ultimately positioned him as a viable presidential candidate. His modesty, combined with a growing sense of purpose and ability to unite and catalyze support, set the stage for his pivotal role in American history leading into the tumultuous Civil War era.

Chapter 15 | Justice and Fairness to All May 1860–November 1860

In the chapter titled "Lincoln Bears His Honors Meekly," we delve into a pivotal moment in American history as Abraham Lincoln navigates his unexpected rise to the presidency during a tumultuous political climate. On May 18, 1860, Lincoln attended a celebratory rally in Springfield following his nomination as the Republican candidate, characterized by the symbolic presence of stacks of wooden rails representing his humble beginnings as a "Rail Splitter." With typical humility, Lincoln addressed the crowd, suggesting that the honor of the nomination belonged to the party rather than to him personally. Despite his inexperienced campaign strategy, which involved staying home more than expected, his political acumen and commitment to “justice and fairness to all” became central themes of his candidacy. In the days following his nomination, Lincoln faced the reality of a divided opposition. The Democrats split into factions, nominating Stephen Douglas and John C. Breckinridge, among others, reflecting deep-seated national tensions over slavery and governance. The emergence of the Constitutional Union Party highlighted the precariousness of the political landscape, as various groups sought to unify around the notion of preserving the Union. 1. Lincoln's approach was marked by a proactive effort to reach out to former rivals within the Republican Party. Negotiations with prominent figures like Thurlow Weed and Salmon P. Chase illustrated his determination to create a coalition that could ensure victory in the face of a fragmented opposition. His desire for inclusivity demonstrated his understanding of party dynamics and the need for unity among constituents. 2. Campaign biographical texts emerged as a key component of political strategy. Biographies were crafted to present Lincoln in a favorable light, reflecting his humble roots and legal prowess. Scripps’ pamphlet biography gained traction, establishing Lincoln’s image as a relatable candidate. 3. Mary Lincoln played a significant role in the campaign, going beyond the traditional, reserved role of a candidate's spouse. Her active engagement in political discourse and relationship management served not only to bolster her husband's image but also to illustrate a partnership that was politically savvy and deeply involved in the nuances of the campaign. As Lincoln prepared to contest the presidential election, the dynamics of political engagement shifted. The arrival of visitors and supporters at his Springfield home underscored his growing status as a national figure. Despite the parades and crowds, Lincoln maintained a humble stance, often reflecting on the weight of his new responsibilities. 4. Through a strategic blend of silence on key contentious issues and a focus on party unity, Lincoln navigated the treacherous political waters leading up to the election. He was acutely aware of the importance of early electoral victories and monitored results closely from key states, such as Pennsylvania and Ohio. 5. On election day, as Lincoln cast his vote, he was met with public enthusiasm. The subsequent reports of victories solidified his position, culminating in his election as the sixteenth president of the United States. The culmination of these events of November 6, 1860, was marked by a mix of personal joy and the understanding of the challenges that lay ahead. Ultimately, Lincoln's journey from Springfield to the presidency reflected a complex interplay of personal humility, political strategy, and the ability to unite a fractured party amidst an era of division. As he embraced the title of president-elect, his response to the outcome revealed a mix of elation and the recognition of the grave responsibilities he would soon undertake in the service of a nation at a crossroads.

Key Point: Embrace humility in the face of success.

Critical Interpretation: Imagine experiencing a moment of triumph—maybe landing your dream job or accomplishing a personal goal. Like Lincoln, you might be tempted to bask in the glory, to revel in the accolades and honors bestowed upon you. Yet, the true essence of lasting leadership lies in humility; it’s the acknowledgment that these achievements are not solely a testament to your greatness but a reflection of the efforts of many, including colleagues, mentors, and community support. When you embrace this humility, you foster collaboration and unity, much like Lincoln did in a divided political landscape, reminding yourself and those around you that success is a shared journey, paving the way for even greater collective accomplishments. By doing so, you not only elevate your character but also inspire others to engage and contribute, cultivating an environment of support where everyone can thrive.

Chapter 16 | An Humble Instrument in the Hands of the Almighty November 1860–February 1861

In this chapter of "A. Lincoln," Ronald C. White Jr. details the crucial transitional period in Abraham Lincoln's life as he prepares to assume the presidency during a time of national crisis and potential secession. The narrative unfolds the complexities of Lincoln's situation and the unprecedented challenges he faced upon his election. 1. Immediately following his election, Lincoln undertook the monumental task of forming his administration and devising policies to preserve the nation. Understanding the weight of expectation, he acknowledged that his responsibility was greater than that faced by his predecessor, George Washington. While he maintained optimism about averting conflict, his isolation in Springfield clouded his perception of the dangers of secession and war. 2. Lincoln's cabinet selection became a strategic concern, and he sought leadership figures with prior experience, including former rivals. This selection process demonstrated his intention to achieve geographic and ideological balance in his administration. Despite his minority electoral victory and a lack of Southern support, Lincoln remained committed to a firm stance against the extension of slavery. 3. As political tensions rose, Lincoln initially misjudged the South's agitation for secession, which was fueled by his election. Despite warnings from allies regarding the secessionist movement, Lincoln opted for a policy of silence, which muted his usual persuasive abilities. 4. Meanwhile, Lincoln's preparations for a long transition included maintaining a busy schedule in Springfield. He engaged with political leaders and the public, all while starting to craft his inaugural address amidst the growing unrest. Through networking and discussions, Lincoln began to outline a government reflective of the Republican values he championed during his campaign. 5. As secessionist sentiments intensified, Lincoln remained focused on forming a cabinet and reaching out to potential allies in the North and border states. His reluctance to compromise on slavery issues emerged as a defining characteristic, despite pressures from various factions within his party advocating for different approaches. 6. Faced with a divided Republican party, Lincoln continued to emphasize a strong stance against the expansion of slavery while also seeking to reassure the South that their rights would be respected. The Crittenden Compromise, aimed at easing tensions, was ultimately rejected by Lincoln, who feared it could lead to the proliferation of slavery. 7. Lincoln's farewell address in Springfield foreshadowed his impending challenges with eloquence and emotion. As he departed for Washington, he addressed his supporters, expressing the weight of the task ahead and invoking a sense of divine providence to guide him through the trials he anticipated. 8. The journey from Springfield to Washington marked a pivotal moment where Lincoln articulated his vision for leadership, though overshadowed by dark whispers of potential assassination plots. His speeches along the route, stressing unity and the principles of democracy, revealed his clear recognition of the tumultuous atmosphere that engulfed the nation. 9. The contrasting narratives of Lincoln and Jefferson Davis highlighted the rapidly escalating divide within the country. While Lincoln pushed for reform and preservation of the Union, Davis, as the leader of the Confederacy, articulated a vision for an independent Southern nation based on principles of slavery. Through this multifaceted exploration of Lincoln’s political ascent and his emotional farewell, White paints a vivid portrait of the man grappling with the magnitude of leadership in an unprecedented era. With a tapestry of political maneuvering, personal conviction, and emotional depth, the chapter illuminates the complexities of Lincoln's early presidency and the impending Civil War.

Chapter 17 | We Must Not Be Enemies February 1861–April 1861

In February 1861, Abraham Lincoln's incognito arrival in Washington, D.C. set the stage for his presidency amidst turmoil. His journey, akin to that of a fugitive seeking safety, was emblematic of the tensions gripping the nation. Lincoln’s initial interactions, notably with President Buchanan and Governor Seward, highlighted both his diplomatic approach and the precarious political landscape. Lincoln's first morning in the capital was marked by a blend of new friendships and political maneuvering as he sought to solidify his cabinet and delicately navigate party allegiances. 1. First Impressions and Relationships: Upon meeting key political figures, Lincoln's rapport with rivals like Stephen Douglas demonstrated a willingness to build unity across party lines during a time of division. Their personal meeting signified a mutual respect that transcended previous political animosities. 2. Preparations for the Inauguration: The days leading up to Lincoln's inauguration were hectic and filled with social obligations, underscored by concerns over the looming secession crisis. Amidst celebratory gatherings, criticisms arose regarding Lincoln's focus on cabinet appointments over urgent national issues, reflecting public skepticism of his executive capabilities. 3. Inaugural Address: On March 4, 1861, Lincoln delivered an inaugural address that was carefully crafted to project unity and reconciliation, seeking to quell Southern fears of a Republican administration. He emphasized the inviolability of the Union and the need to uphold the Constitution, suggesting that any act of aggression would originate from the secessionists, thus framing the narrative of the conflict. 4. Public and Political Reactions: Following the speech, reactions were sharply divided. While some publications praised Lincoln's conciliatory tone, others deemed it cowardly or ineffective. Prominent figures like Frederick Douglass expressed disappointment in Lincoln's commitment to the fugitive slave law, questioning the seriousness of his intentions toward emancipation. 5. Crisis at Fort Sumter: Almost immediately, Lincoln confronted a critical challenge: the situation at Fort Sumter. Under pressure to act decisively, he grappled with whether to resupply or surrender the fort, weighing the potential consequences of either decision. Advisers were divided, with some urging caution to avoid provoking war, while others believed maintaining authority was essential. 6. Decision to Resupply Fort Sumter: Ultimately, after extensive consultations and experiencing mounting impatience from various political factions, Lincoln resolved to send supplies to Fort Sumter, viewing it as both a necessary action and a statement of resolve. This crucial decision set in motion events that would lead to the outbreak of the Civil War. 7. Influence of Cabinet Dynamics: Throughout this period, the dynamics within Lincoln’s cabinet played a significant role in his decision-making process. He navigated differing opinions while reinforcing his own authority, signaling a growing confidence in his leadership abilities. 8. The Outbreak of War: The situation escalated swiftly, ending in the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, which galvanized Northern sentiment and unified previously fragmented opinions around the necessity of defending the Union. This marked the beginning of open hostilities and solidified Lincoln’s role as a wartime leader. Through his first weeks in office, Lincoln’s journey involved cultivating relationships, handling political pressures, and making pivotal decisions that would define his presidency. His careful balance of reconciliation and firm leadership in the face of crisis laid the groundwork for his enduring legacy.

Key Point: Building Unity Across Divisions

Critical Interpretation: As you navigate your own life, consider how Lincoln's approach to building unity among rivals can inspire you to seek common ground in your relationships. In a world often marked by division and conflict, embracing the willingness to engage with those who hold differing views can be transformative. Just as Lincoln fostered mutual respect and understanding amidst the heated political climate of his time, you too can strive to create connections that transcend differences, fostering peace and collaboration in both your personal and professional interactions.

Chapter 18 | A People’s Contest April 1861–July 1861