Last updated on 2025/04/30

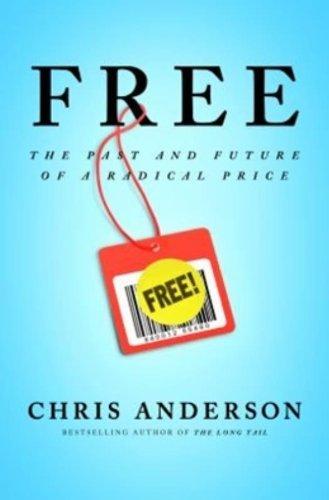

Free Summary

Chris Anderson

How Zero Cost is Revolutionizing Business and Society

Last updated on 2025/04/30

Free Summary

Chris Anderson

How Zero Cost is Revolutionizing Business and Society

Description

How many pages in Free?

288 pages

What is the release date for Free?

In "Free: The Future of a Radical Price", Chris Anderson boldly explores the transformative power of the concept of free in today’s digital economy, where traditional pricing models are challenged by the limitless possibilities of the Internet. With compelling insights and real-world examples, Anderson illuminates how businesses—from startup innovators to established giants—are leveraging the allure of no-cost offerings to capture attention, foster community, and ultimately drive profitability in unexpected ways. As he delves into the psychological and economic implications of making products and services free, readers are invited to reimagine their own business strategies and consumer behaviors in a world where the price tag is no longer a barrier but an opportunity. Join Anderson on this provocative journey that not only unveils the mechanics behind the free economy but also encourages us to rethink the value of what we offer and consume in an increasingly connected world.

Author Chris Anderson

Chris Anderson is a prominent author, entrepreneur, and former editor-in-chief of Wired magazine, widely recognized for his insights into the evolving landscape of technology and business. He gained acclaim for popularizing the concept of the "long tail" in his bestselling book of the same name, which explored how the internet empowers niche markets and changes consumer behavior. Anderson's work focuses on the impact of digital technology on economics and society, arguing that the new economy is increasingly defined by free goods and services. Through his writings, including "Free: The Future of a Radical Price," he challenges traditional business models and inspires readers to reconsider the value of their own offerings in a world where the cost of distribution has dramatically diminished. His thoughts resonate with entrepreneurs and tech enthusiasts alike, making him a significant voice in discussions about innovation and the future.

Free Summary |Free PDF Download

Free

Chapter 1 | THE BIRTH OF FREE

In the first chapter of "Free" by Chris Anderson, the author presents a compelling narrative about how the concept of "free" evolved into a powerful marketing and economic strategy. The chapter begins with the historical origins of Jell-O, highlighting Pearle Wait's initial struggles in marketing gelatin and his innovative idea of adding flavor and color to create appeal. Despite early failures in sales due to consumer unfamiliarity, the eventual purchase of the Jell-O brand by Orator Frank Woodward set the stage for a transformative marketing campaign. 1. Through strategic advertising in "Ladies’ Home Journal" and the distribution of free recipe pamphlets, Woodward effectively created demand, illustrating how "free" could serve as a powerful inducement to spark interest in unfamiliar products. This approach allowed him to circumvent the restrictions on door-to-door sales, gifting valuable content that encouraged consumers to embrace Jell-O—ultimately leading to its massive success. 2. The author draws parallels between Jell-O's marketing strategy and the innovative business model of King Gillette, who introduced disposable razors. Initially, he struggled with poor sales until he adapted a strategy of offering razors at a low cost to various partners, who would then give them away to foster a customer base reliant on purchasing replacement blades. This tactic created a symbiotic relationship between the product and its consumers, ensuring repetitive revenue from blade sales. 3. As the narrative unfolds, the text connects the early 20th-century marketing methods with the modern digital economy, emphasizing a shift from the traditional atoms economy to a bits economy, where the costs of goods and services are driven down to near zero. In this new era, once something becomes digital, it has the potential to be free, contrasting with the historical understanding of free in the physical economy, which often felt like a trade-off or bait-and-switch. 4. In the contemporary landscape, numerous industries have adopted this "freeconomics" framework. Instances abound where companies offer free services—music, games, online content—recognizing that this strategy can generate widespread user engagement while also paving the way for additional revenue through avenues like live events or premium content. The advent of digital tools further accelerates this trend of free offerings, as technological advancements continue to lower operational costs. 5. The chapter concludes by positing that in the current economy, understanding and employing the concept of "free" is not just necessary but vital for success. The text foreshadows the exploration of how to effectively leverage this model in business, indicating that future chapters will unpack the principles underpinning "free," elucidating its significance in the ever-evolving economic landscape. Overall, Anderson’s dissertation on the birth of free establishes a foundational understanding of how this concept has encapsulated consumer psychology, influenced purchasing behavior, and been redefined by the advent of digital economics, shaping everything from marketing strategies to business models for the twenty-first century.

Key Point: Embracing the Principle of 'Free'

Critical Interpretation: Imagine stepping into a world where the very act of giving something away could yield unimaginable returns; Chris Anderson’s exploration of the 'free' model compels you to rethink how you engage with your daily choices, work, and interactions. Just as Orator Frank Woodward revolutionized Jell-O by offering enticing free recipes, you too hold the power to ignite curiosity and connection by sharing your skills or knowledge without immediate expectation of return. This philosophy encourages you to foster relationships and communities, paving the way for collaborations that may seem risky at first but can lead to remarkable opportunities. The essence of 'free' lies not in absence of value, but in its ability to break barriers, inspire trust, and ultimately cultivate a wealth of possibilities you might have never anticipated—so go ahead, give something away today; you might just be surprised at what comes back to you.

Chapter 2 | WHAT IS FREE

The concept of "Free" is multifaceted and has evolved significantly over time, often stirring skepticism while simultaneously captivating our attention. Understanding the nuances of what "free" truly means is essential, particularly as we move toward an economy centered around it. In various cultures and languages, especially those rooted in Latin, the term is split into distinct parts: "liber," meaning freedom, and "gratis," referring to something given without compensation. This duality is less clear in English, where "free" encompasses both definitions, leading to ambiguity in its interpretation. 1. Understanding Free: The term "free" has its origins in the Old English words linked to notions of love and friendship, hinting at a broader social context connecting freedom with costlessness. Today, the discussion primarily revolves around "free" as zero cost or as a marketing tool. 2. Varieties of Free: In the commercial landscape, "free" adopts numerous meanings and business models. For example, promotions like "buy one, get one free" hinge upon psychological pricing strategies rather than actual cost savings. Likewise, "free shipping" typically includes hidden costs allocated into product pricing. While some concepts, such as "free samples" and "free trials," appear genuine, they often aim to stimulate future purchases or create a feeling of moral obligation. 3. Economic Models of Free: The dynamics of free are underpinned by cross-subsidies, where the costs associated with a free product are compensated through other expenditures or by third parties. This concept emphasizes that nothing is truly free; costs are shifted either to the consumer indirectly or across different segments of the market. 4. Cross-Subsidies Explained: Cross-subsidies manifest in various ways in the economy. Products like "loss leaders" encourage purchases of other items, while long-term payment strategies (like contracts for free cell phones) allow consumers to enjoy immediate benefits at the expense of future payments. Segmenting consumers into groups willing to pay versus those who are not also exemplifies this strategy, as seen in services that target select demographics. 5. Categories of Free: Within the broad sphere of cross-subsidies, we can delineate four main types: - Direct Cross-Subsidies: This includes products offered at reduced or no cost to entice consumers to purchase other higher-margin goods. Retail strategies often lean on this principle, manipulating perceptions of value. - Three-Party Markets: Here, core offerings are free for consumers while advertisers pay to access the audience. This symbiotic relationship breeds an ecosystem greatly evident in traditional media and is now expanding across multiple industries on the internet. - Freemium Models: The digital realm frequently employs this model, offering basic services for free while charging for premium features. This demonstrates the unique nature of digital goods, where serving additional users incurs negligible costs. - Non-Monetary Markets: Here, individuals voluntarily share or provide goods and services without expectation of payment. This includes the "gift economy," where contributions are made out of altruism or for non-cash rewards, highlighting a significant shift in understanding value. 6. Negative Pricing: An interesting paradigm emerges with "negative pricing," where consumers are incentivized with cash for using certain services, challenging conventional pricing structures. This phenomenon is reflected in various loyalty and cash-back programs, reshaping consumer expectations and behaviors around expenditure. 7. Real-world Applications: Exploring instances like FreeConferenceCall.com reveals innovative strategies that upend traditional revenue models – in this case, earning through affiliate payments rather than direct customer fees. The intricate web of economic relationships illustrates the complexity of "free" in practice. In conclusion, the concept of "Free" intersects with various economic models and social nuances, reminding us that what may appear as a simple transaction often entails a complex web of relationships and dependencies. Understanding this landscape is crucial as we navigate an increasingly interconnected and economically diverse world.

Key Point: The Duality of 'Free'

Critical Interpretation: As you navigate your life and decisions, consider the dual nature of 'free' defined in Chris Anderson's exploration of the term: 'liber', representing freedom, and 'gratis', representing costlessness. This invites you to reflect deeply on what true freedom means to you. When presented with something labeled as 'free', remember that it might not only be about the lack of monetary cost but also about the inherent value or obligation that may accompany it. By recognizing this duality, you can make wiser choices, understanding that what feels 'free' could also be entangled with hidden costs or expectations. This insight encourages you to seek true freedom in your life, prioritizing genuine connections and exchanges that enrich your journey, not just those that entice you with a zero price tag.

Chapter 3 | THE HISTORY OF FREE

The exploration of the history of Free, as articulated in Chris Anderson's "Free," begins with a philosophical inquiry into the essence of "nothing." This concept, while abstract, has profound implications across various domains including mathematics, economics, and societal interactions. The narrative kicks off with the Babylonians, who, facing the need to quantify voids within their numeral system around 3000 B.C., became the first civilization to conceptualize zero, thus paving the way for later mathematical advancements. 1. The Birth of Zero: The Babylonians devised a system using a pair of wedge symbols to represent different values, leading to the invention of zero as a placeholder. However, its acceptance and utilization were notably slow across cultures. The Greeks, primarily focused on geometry, eschewed it as a concept that contradicted physical reality. 2. Indian Contributions: The mathematical prowess of Indian scholars offered a different perspective; they considered numbers as abstract concepts devoid of physical manifestation. Their acceptance of zero by the 9th century, articulated through the term "sunya," marked a pivotal progression in mathematical thought. 3. Free in Everyday Transactions: By the turn of the first millennium, economic interactions were, in many cases, governed more by social bonds than monetary exchange. The essence of Free, embodied by trust and generosity within communities, called into question the need for price tags in intimate transactions. 4. The Evolution of Economic Systems: As economies matured from familial and tribal interactions into nation-states and market-driven systems, the concept of Free persisted, often illustrated through charity, government funding, and community initiatives, albeit in a transformed context that introduced structured taxation and institutionalized support. 5. Resistance to Interest: Historical resistance to interest rates—seen as exploitation—began with the Catholic Church and echoed throughout various religious doctrines. As societies evolved, the pragmatic need for interest on loans emerged, demonstrating that economic landscapes can shift with time. 6. Enlightenment and Capitalist Markets: With the rise of capitalism in the 17th century, money solidified its role as the primary medium of exchange. Pioneers like Adam Smith framed commerce as integral to human interactions, emphasizing that market transactions are effective due to pricing mechanisms that facilitate production. 7. Alternative Economic Models: However, counter-movements led by thinkers like Karl Marx and anarchist Peter Kropotkin critiqued capitalism, proposing systems where mutual aid, communal ownership, and spontaneous labor mitigated the need for monetary compensation. 8. The Concept of Free Lunch: In the 19th century, as consumer culture burgeoned, the phrase “there’s no such thing as a free lunch” emerged, illustrating the tension between suspicion towards Free offerings and their perceived value in marketing. 9. Re-emergence with Consumer Goods: The early 20th century revitalized the idea of Free through marketing strategies that included free samples, exemplified by Benjamin Babbitt’s soap promotions, signifying a shift in consumer engagement and competition. 10. The Disruption of Markets: The digital revolution set the stage for Free to subvert traditional market structures. Realizing that charging nothing for a product can attract customers en masse, businesses began leveraging Free as part of strategic market entry, as seen in music and telecommunications. 11. The Emergence of Abundance: The narrative transitions to a broader societal context, wherein abundance has defined recent generations, shifting focus from scarcity—a primary concern of the past—to abundance in resources like food, driven by technological advances in agriculture. 12. Corn Economy and Industrialization: The case of corn illustrates how agricultural advancements, particularly in fertilizer technology, significantly increased crop yields, thereby altering societal structures and economic dynamics. 13. Debates on Resource Scarcity: Historical tensions between scarcity and abundance came to a head during the late 20th century with the notable Ehrlich-Simon bet, which demonstrated that, contrary to scarcity predictions, the prices of many resources had fallen, proving the power of human innovation over time. 14. Cultural Perceptions of Abundance: Society's tendency to overlook abundance contrasts sharply with its fixation on scarcity. As resources become abundant, they often fall out of consideration, leading to cultural shifts toward disposability—as seen in fashion and consumer goods. 15. Future of Economic Value: The dynamics of value continue to evolve, with abundant resources often rendering previous economic models obsolete. Entrepreneurs and innovators must anticipate which sectors will create new scarcities and drive future economic growth, further solidifying the principle of abundance at the center of economic discourse. Through this narrative, Anderson elegantly highlights the philosophical and practical implications of Free, illustrating its historical trajectory, societal significance, and the ongoing struggle to balance concepts of scarcity and abundance in the ever-evolving economic landscape.

Chapter 4 | THE PSYCHOLOGY OF FREE

In 1996, the Village Voice transitioned to a free distribution model after years of dwindling readership. This pivotal moment was seen by many as a decline in the paper's cultural relevance, contrasting sharply with the success of the satirical publication The Onion, which has thrived as a free paper since its inception. This juxtaposition raises the question of why "free" led to the demise of one publication while propelling another to success. The answer lies in the nuanced psychology surrounding free offerings. 1. Perception of Value: When a paid product becomes free, consumers often perceive a reduction in quality. However, items that have always been free don’t carry that same stigma. The Village Voice, for example, had already been experiencing a decline in its core metrics prior to going free. It was the cost model adjustment that saved it, not necessarily the shift to free distribution itself. Thus, the perception of quality varies depending on whether the product was formerly charged for. 2. The Pricing Psychology of Free: Analyzing magazine pricing illustrates this phenomenon. A free online magazine maximizes audience reach through ad revenue, while traditional print pricing creates a divide between what consumers are willing to pay and what publishers should charge to maintain profitability. A $10 annual subscription is low enough to attract a vast audience, yet high enough to maintain perceived value, attracting advertisers willing to pay more to reach engaged subscribers. 3. The Penny Barrier: Even a nominal fee, like one cent, creates a mental hurdle for consumers. This concept, termed "mental transaction costs," implies that any cost, no matter how small, compels consumers to evaluate their purchase decisions. As a result, free services tend to see a much higher engagement as consumers confront fewer barriers to entry. 4. Behavioral Economics and Free: Research in behavioral economics shows that the allure of free products stems from an emotional excitement associated with not incurring costs. As demonstrated in experiments with chocolate choices, consumers often favor free items regardless of their relative quality. 5. The Struggle for Value: Even when items are free, perceived social costs can factor into decision-making. Offers like free shipping can incentivize larger purchases, but small fees can disrupt this behavior, as seen in variations of policy in different countries. The distinction between free shipping and minimal charges illustrates the complexities of how we value products. 6. Impacts of Free on Consumption: While free products can maximize participation, they may also lead to irresponsible consumption, as individuals often feel less ownership over items that come at no cost. Conversely, low fees can encourage careful usage, as evidenced by a charity’s need to charge nominal fees to ensure accountability in the use of bus tickets. 7. Time vs. Money: The idea that consumers' priorities shift from valuing time over money to vice versa as they age is central to the freemium model’s effectiveness. Younger customers may prefer free, time-consuming alternatives, while older consumers gravitate toward paid services that save them time. 8. Open Source Dynamics: The principle of providing free information to foster community engagement enables businesses to monetize through premium products. An example is DIY Drones, demonstrating how free offerings can bolster confidence in products and encourage larger communities of users. 9. The Reality of Piracy: The phenomenon of piracy highlights consumer perceptions of value and accessibility. Often viewed as a victimless crime, piracy can also serve to enhance a product’s reach, where pirated goods don’t entirely replace originals but can provide opportunities for firms to adjust pricing and improve perceived value. In conclusion, the relationship between free offerings and consumer behavior is multifaceted. It is influenced by psychological factors while also demonstrating the importance of perceived value and commitment. The implications of adopting free strategies must be carefully navigated to align with objectives, whether to maximize exposure or maintain quality and consumption awareness. Ultimately, understanding the dynamics of free can empower companies to adapt in an increasingly digital marketplace where consumers expand their preferences based on perceived value rather than mere cost.

Key Point: Perception of Value

Critical Interpretation: When you consider the dynamics of 'free' within your own life, reflect on how the quality of experiences or products you encounter can shift based on cost. If you've ever hesitated to engage with something free, thinking it might come with inferior quality, you're not alone. Yet, what if you approached 'free' with an open mind? By embracing opportunities—whether they are workshops, online courses, or community events—that don’t demand a financial commitment, you could unlock a wealth of knowledge and connections. This shift in perception invites you to take risks and explore avenues you might otherwise overlook. Ultimately, understanding this psychology could inspire you to pursue passion projects, learn new skills, or foster relationships in environments where collaboration and creativity thrive, all without the fear of diminished value.

Chapter 5 | TOO CHEAP TO MATTER

In "Free," Chris Anderson explores the profound changes brought about by the decreasing costs of digital technologies, encapsulated in the overarching concept that certain forms of technology are becoming "too cheap to meter." At the heart of this discussion lies a reflection on how rapidly the costs of computing power, digital storage, and bandwidth are plummeting, fundamentally reshaping our economy and society. 1. Historical Context and Predictions The chapter opens with a historical nod to Lewis Strauss’ 1954 prediction that electrical energy would become "too cheap to meter." Strauss envisioned a future where technology would alleviate many of humanity's challenges. However, the expected transformation did not materialize; while nuclear power became feasible, it remained expensive. This serves as a springboard for contemplating a world where digital technology truly becomes free, altering the fabric of everyday life and economic structures. 2. The Three Pillars of Digital Abundance The current technological paradigm hinges on three main pillars: computer processing power, digital storage, and bandwidth. These technologies have consistently halved in price over the years while simultaneously doubling in capacity or performance. Moore’s Law captures this phenomenon in terms of processing power, yet storage and bandwidth have proven to be even more accelerated. Such exponential growth leads to remarkable cost efficiencies in virtually every domain of the digital economy. 3. Anticipating Cheaper Futures Anderson highlights the concept of "anticipating the cheap," as exemplified by Fairchild Semiconductor’s strategic decision to price transistors well below their manufacturing costs, knowing market trends would eventually support lower prices. By creating demand through immediate access to cheaper products, companies can stimulate growth even in the face of cost declines, enabling them to capture substantial market share. 4. The Expanding Definition of Economies The chapter also challenges conventional economics, suggesting that with digital technologies, the natural trend is toward perpetual decrease in prices as production scales. Moore's Law, now exceeding the bounds of traditional economics, illustrates a shift toward abundance rooted in ideas rather than materials, where the cost of creating value diminishes as efficiency increases. 5. Wasting Technology for Innovation Drawing insights from Caltech professor Carver Mead, Anderson argues that when technology becomes abundantly cheap, the focus should shift from conservation to innovation. Instead of rigorously metering resources, tech should be allowed to proliferate, harnessing its value in ways that nurture creativity and discovery. This principle laid the groundwork for developments like graphical user interfaces and has significantly influenced how conventional computing infrastructure has evolved. 6. Transformative Effects on Various Industries As storage and bandwidth evolved parallel to processing power, each segment experienced transformations that drove accelerated innovation across various sectors. Key advancements, particularly in media consumption with platforms like YouTube and services such as Gmail, have emerged primarily due to significant reductions in cost and increase in availability. 7. Cumulative Economic Impact Finally, Anderson underscores that the rapid decline in costs across these digital technologies has fundamentally altered supply and demand dynamics. While traditional economic theories apply within temporal snapshots, the dominant long-term trend toward zero pricing influences how products evolve and interact. This not only fuels a cycle of commodification but also creates new opportunities to innovate — underscoring a continuous revolution that is still in its infancy. Anderson's analysis elucidates how, as technology becomes increasingly prevalent and inexpensive, it facilitates an unprecedented expansion of creativity, accessibility, and innovation, refuting traditional economic constraints and transforming industries. The chapter encapsulates a crucial moment in the evolution of the economy—one where the logic of abundance reshapes our understanding of value, consumer behavior, and the very fabric of society.

Chapter 6 | “INFORMATION WANTS TO BE FREE”

In 1984, journalist Steven Levy made a significant contribution to the understanding of the computing revolution with his book "Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution," documenting the ethos of the burgeoning hacker community. Within this subculture, he identified seven key principles, among which one stood out: all information should be free. This idea can be traced back to a 1959 claim by Peter Samson of MIT, who emphasized the unrestricted access to information essential to learning and innovation. Levy’s work piqued the interest of influential figures like Kevin Kelly and Stewart Brand. Brand, this prominent voice from the counterculture movement, aimed to distill the essence of hacking ethics into discussions at the 1984 Hackers Conference. This gathering brought together notable figures such as Steve Wozniak and Richard Stallman to articulate and refine the idea of the hacker ethic. It was during this conference that Brand famously articulated a complex duality regarding information economics, stating, "Information wants to be expensive because it’s so valuable. On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of getting it out is getting lower and lower." This paradox encapsulated a significant tension within the emerging digital age, highlighting the coexistence of differing economic realities in the world of information. 1. Brand's insight captured the simultaneous conflict within the digital landscape: the desire for information to be available at little to no cost contrasts starkly with its high potential economic value. While the cost of distribution decreases, the demand for unique, high-quality information remains strong. This reflects the fundamental nature of economics; information becomes a commodity that can readily be reproduced or customized, thereby altering its market value. 2. The original phrase by Samson emphasized the importance of unrestricted access to information as a foundational principle of the hacker ethos, suggesting the right of all individuals to learn and innovate without barriers. Brand transformed this imperative from a moral dictate into a more fluid, descriptive metaphor, implying that information inherently strives for freedom in its distribution, akin to a natural law. This transition from "should" to "wants to" indicates a shift from a rigorous philosophy to a concept reflecting the inevitable progression and economic realities of information in society. 3. Within the dynamics of digital economics, Brand’s assertion reveals that abundant information tends to fall in value, leading to a natural inclination towards "free" as a conventional reality. On the contrary, valuable and scarce information retains a higher price in the marketplace. This distinction is illustrative of how the context in which information is offered can add to its perceived value. Customized or contextualized information, tailored to specific needs, commands a premium, whereas general, widely accessible information ebbs towards a zero-cost status. 4. To fully grasp the implications of Brand’s observations, one must also consider the evolution of language surrounding information itself. Traditionally defined and understood through the lens of news and facts, the term shifted due to advancements in technology, particularly highlighted by Claude Shannon’s groundbreaking information theory. His exploration of signal processing laid the foundation for distinguishing meaningful data from noise, thus establishing the modern understanding of information as a digital construct. 5. Brand's approach also questioned the undercurrents of how value is realized. He noted that the product is not the information per se; rather, businesses often monetize the channels through which this information flows—whether through advertisements, subscription models, or ancillary services. The essence of information and the consequent business models spring from the recognition that content and interaction can be commodified in creative ways, leading to diverse economic opportunities beyond the information itself. Ultimately, Brand’s phrase “information wants to be free” has often been misrepresented as a definitive statement advocating for unrestricted access, overshadowing its nuanced contemplation about the evolving value and distribution of information in the digital economy. This duality invites a more profound understanding of our engagement with information in a world where the laws of economics constantly push and pull on its value and accessibility.

Chapter 7 | COMPETING WITH FREE

In the competitive landscape of the software and internet industries, companies have learned to innovate and adapt to the challenges posed by the concept of "free." Microsoft, having established itself over decades, found itself continually confronted by piracy and new free offerings from competitors, while Yahoo faced a fierce new rival in Google. 1. The Rise of Microsoft and Piracy: In 1975, Bill Gates' open letter highlighted the dilemma software developers face when users treat software as shareable rather than a product deserving compensation. Initially, users copied Microsoft software for free, but as personal computers became mainstream, the idea of paid software solidified. Despite efforts to curb piracy through legal actions and security codes, the challenge persisted, especially in growing markets like China, where illegal copies thrived. Gates' pragmatic approach acknowledged the inevitability of piracy while seeing potential future market gains as these users became accustomed to Microsoft software. 2. Competing with Free Offerings: As competitors arose in the 1990s, like Netscape with its free web browser, Microsoft had to create its own free product to avoid losing market share. This response led to Microsoft bundling Internet Explorer with Windows, which, while effective in countering Netscape, attracted antitrust scrutiny against Microsoft for monopolistic practices. Microsoft's challenge lay not only in competing against free products but also balancing its large market position while maintaining compliance with regulations. 3. Understanding Open Source: The emergence of open source software created a significant threat to Microsoft. Initially, the company viewed Linux as a minor nuisance. However, by the early 2000s, Linux gained considerable ground in the web server market. Microsoft executives eventually recognized the need for a serious strategy against open source, transitioning through stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and finally acceptance of the new reality. This led to the establishment of an open source lab within Microsoft, signifying a shift toward interoperability between Microsoft products and open source, acknowledging a hybrid future in software. 4. Yahoo vs. Google: In early 2004, Google’s announcement of Gmail with an offering of one gigabyte of storage for free posed a direct challenge to Yahoo, the reigning email service provider. Faced with potentially devastating competition, Yahoo executives deliberated on strategies that involved significant investment in infrastructure to match Google’s offering. Following the launch of Gmail, Yahoo responded quickly, increasing its own free storage limits and later offering unlimited storage. Surprisingly, this strategy secured Yahoo's market share, preventing an exodus of users from its premium services. 5. Surviving in the Age of Free: Yahoo's ability to adapt to the competitive threat posed by Google showed that a strategic approach to “Free” could result in profitable outcomes. By preventing abuse through smart software solutions and maintaining user engagement, Yahoo managed to remain the top email service provider. The experience highlights that embracing free offerings can be a viable strategy for established players wanting to retain market relevance against new entrants. Overall, the shifting dynamics of competition illustrate that adaptability to the free model and understanding consumer behavior are crucial for longevity in rapidly changing tech markets. Engaging with rather than resisting free offerings can create opportunities for growth and sustainability despite initial resistance. Both established and new companies can coexist within the hybrid environment where free and paid services offer tailored solutions to diverse user needs.

Key Point: Embracing the Concept of Free as an Opportunity for Innovation

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing at the crossroads of your professional journey, where the landscape is dominated by competitors eager to provide value without a price tag. Chapter 7 of 'Free' by Chris Anderson teaches you that, rather than viewing the 'free' model as a threat, you can harness it as a powerful catalyst for your own innovation. Embrace the challenge: consider how offering a free version of your product could broaden your audience and build a community around your brand. By adapting your strategies to include free offerings, you not only gain invaluable insights into your user base but also position yourself strategically against competitors. Whether you’re launching a startup or revitalizing a legacy business, this mindset shift can ignite your creativity and lead you to untapped opportunities that drive growth and sustainability in an ever-evolving market.

Chapter 8 | DE-MONETIZATION

In Chapter 8 of "Free" by Chris Anderson, the narrative highlights how Google's business model epitomizes the principle of "Free," reshaping the economic landscape. The Googleplex, located in Mountain View, California, stands as a symbol of a company built on giving away products to gain market dominance. Google offers nearly a hundred services free of charge, including word processors and photo editing tools. This remarkable approach contrasts with traditional business practices, as Google prioritizes audience engagement over immediate profit during its product development process. The journey of Google is summarized in three pivotal phases. From 1999 to 2001, Google innovated search algorithms to enhance user experience as the web expanded. Between 2001 and 2003, it embraced a self-service model for advertisers, enabling small businesses to engage with their ads alongside larger corporations. Since 2003, the company has diversified its offerings to deepen customer loyalty and expand the services that can be monetized through advertising, all the while ensuring user experience remains a priority. 1. The foundation of Google's profitability lies in its advertising revenue. The company earns substantial income from ads on core products while freely providing a myriad of other services. This paradigm shift results in minimal costs of entry for new technological ventures, empowering startups to develop without massive investments. As discussed by Paul Graham of Y Combinator, the focus is on creating appealing products rather than on immediate profitability, which allows for business growth without significant risk. 2. Google's infrastructure, comprised of vast data centers, symbolizes its competitive edge. These facilities enable Google to provide services at an exponentially lower cost while continuously improving capabilities with each new data center built. This dynamic drives down the marginal costs associated with offering services online, making it feasible to provide free products without undermining profitability. 3. Through its “max strategy,” Google aims for maximum distribution of its products to engage as broad an audience as possible. Eric Schmidt articulates this philosophy as taking advantage of zero marginal costs to expand presence extensively. While smaller companies may not have an established revenue-generating model like Google's advertising, they can still attract significant attention through free services which, although challenging to monetize, can create substantial opportunities for market engagement. The chapter also delves into the concept of de-monetization, exploring how offering products for free disrupts traditional industries. For instance, Craigslist's free classified ads have significantly eroded the value of print newspapers, illustrating how Free redistributes economic value lowly while simultaneously increasing market efficiency. While the shift can lead to loss for traditional companies, it opens up opportunities for wider accessibility and greater consumer engagement. 4. However, the narrative articulates concerns about the consequences of widespread de-monetization. Critics highlight that while technology leads to lower prices and an abundance of information, it could threaten traditional industries and their employees by compressing economic value into fewer hands. Eric Schmidt warns that this concentration may disadvantage smaller competitors and potentially limit diversity in the marketplace. Furthermore, while Free democratizes access to information, it risks leaving legacy businesses in disarray, as evidenced by the decline of newspapers. 5. Ultimately, the success of the Free model merits continued scrutiny, especially concerning its long-term effects on wealth distribution across economies. Although it appears that a few companies, primarily Google, dominate the Free landscape, there are indications that evolving business models may allow for broader wealth generation opportunities through innovative uses of Free in media and beyond. Thus, the chapter presents a nuanced exploration of Google’s disruptive approach and the broader implications of Free in contemporary economics. It suggests that while Free can lead to more efficient markets, the current landscape carries complexities that warrant careful examination as technology continually evolves.

Chapter 9 | THE NEW MEDIA MODELS

Chris Anderson's Chapter 9 from "Free" delves into the evolution of media models, specifically focusing on the expansion of ad-supported free content in the digital age. The chapter begins with a historical perspective, tracing the origins of broadcast media to the early 20th century when radio became a mass entertainment platform. Despite its popularity, the significant challenge was determining a sustainable funding model for content. Various proposals emerged, including taxes and listener contributions, yet advertising ultimately changed the landscape, becoming a primary funding source. 1. The emergence of advertising allowed radio to flourish, giving rise to the three-party model that still dominates the media landscape today: content creators produce material for audiences funded by advertisers. This model proved effective as it ensured that vast audiences could access content for free, establishing the foundation for today's $300 billion advertising industry. 2. The chapter emphasizes how this ad-based model is transcending traditional media, extending into software and user-generated content online. Notably, online advertising transforms conventional practices by matching ads with relevant content, which alters traditional notions of trust and audience engagement. This strategic alignment results in ads being perceived as less intrusive, ultimately cultivating a more receptive audience. 3. Meanwhile, traditional media has faced challenges as content consumption shifts from paid to free. The rise of the internet has amplified the expectation for free content across all formats, undermining the previous reliance on subscriptions and physical media sales. The generational shift towards free content models is further attributed to various factors such as increased supply, lower perceived value of digital content, heightened access to free media, and the influence of tech companies advocating for free services. 4. Despite concerns regarding the saturation of advertising dollars, the chapter promotes the idea that advertising will be an enduring support model for both traditional and emerging media companies. It elaborates on how traditional advertising, marked by scarcity, contrasts with the boundless opportunities available online, where fulfilling the needs of targeted users has become a new paradigm. 5. Anderson also explores the dynamic nature of online advertising, distinguishing between traditional display ads and performance-based models exemplified by Google’s cost-per-click approach. This illustrates the shift toward more effective and measurable advertising strategies that leverage user intent and behavior, driving immense value for advertisers. 6. As media converges with the gaming industry, the chapter highlights the rapid transformation occurring within video gaming. This industry is experimenting with innovative free-to-play and freemium models that reflect broader economic shifts toward free access. Successful strategies, such as selling virtual goods, subscriptions, and integrating ads, illustrate the ongoing evolution of traditional media models. 7. Additionally, free models are not only reshaping the gaming industry but also contributing to the evolution of music and literature. The success of artists like Radiohead, who released their albums through name-your-price schemes, underscores how embracing free content can build audience engagement and drive ticket sales for live performances. 8. The chapter concludes by affirming that free content strategies – whether in music, gaming, or literature – proliferate as they enhance market reach and engagement potential. Redefining the value proposition for content in the age of digital abundance emphasizes the ongoing need for creators and industries to adapt and innovate to thrive in this new ecosystem. In essence, Anderson's analysis of the new media models elucidates how the principles of free content intersect with traditional media strategies, reshaping the landscape of creative industries in our increasingly digital world. The chapter serves as both a historical overview and a forward-looking exploration of how various sectors can thrive by embracing the evolving nature of free media.

Key Point: Embrace the Free Model to Enhance Engagement and Innovation

Critical Interpretation: Imagine how your life could transform if you adopted the principle of free content in your own endeavors—whether in your career or personal projects. Just like artists who release music without charges to cultivate a larger audience, you too can create offerings that invite engagement rather than impose costs. By sharing your ideas freely and inviting feedback, you open doors to collaboration and innovation, fostering a community that connects over your shared interests. This shift towards a 'freemium' approach encourages your audience to become active participants in your journey, ultimately enhancing your influence and building deeper relationships. Embracing free as a core principle empowers you to redefine value, making room for unexpected opportunities that arise from connections and experiences rather than transactions.

Chapter 10 | HOW BIG IS THE FREE ECONOMY

In assessing the scale of the Free economy, the enigmatic nature of "free" itself complicates matters, rendering a straightforward answer elusive. The inquiry often surfaces as, "How big is the Free economy?" but this requires a discerning approach due to its varied dimensions, encompassing everything from the conventional business economy to informal volunteerism. Notably, the essence of "free" often escapes monetary measurement; countless acts of unpaid kindness go unrecorded, while marketing ploys like "buy one, get one free" fail to signify a legitimate economic paradigm. First, while free as a marketing strategy is pervasive across industries—from trial offers to promotional giveaways—it's primarily a mechanism of cross-subsidy rather than a standalone market. This notion leads to the exploration of nonmonetary economies based on reputation and attention, which, while impactful, defy straightforward valuation in traditional financial terms. These include creative advertising campaigns like Burger King's "Whopper Sacrifice," which encouraged users to "unfriend" people on Facebook in exchange for burgers, thereby showcasing the intricate relationship between social engagement and reputational capital. Second, tools of measurement have been employed to estimate the value of these quasi-currencies. For instance, the discussion around Facebook's valuation can be illuminated by attempts to quantify the worth of a social connection or "friendship." Rough estimations of a friendship's value through various metrics have produced figures suggesting Facebook's worth could fluctuate significantly based on user engagement. Third, the quantification of attention spans and reputational capacities invites probing inquiries, particularly in an era where digital platforms allow individuals to maintain extensive social networks far beyond anthropological norms, such as the "Dunbar number," which suggests a cognitive limit on meaningful relationships. Fourth, when calculating the Free economy in concrete terms, advertising-supported media emerges as a pivotal sector. The advertising revenue from traditional media like radio and television expired at approximately $45 billion, to which online advertising adds another potential $21 to $25 billion. Inclusive of print publications, the rough total for these ad-driven segments ranges from $80 to $100 billion in the U.S. alone. Fifth, the freemium model, where a small percentage of customers support a larger base of free users, is another growing segment. The corporate side of this ecosystem is estimated to draw $800 million, while consumer engagement may contribute at least equally. Additional sectors such as open-source software could add around $30 billion, creating a near-comprehensive illustration of a freemium market estimated at approximately $36 billion. Lastly, the intricate threads of the gift economy remain difficult to quantify but are vital in appreciating the broader value accrued through free offerings. For example, the music shared on platforms like MySpace or the music libraries stored on devices like iPods demand an acknowledgment of the sprawling economic impact of free access. In sum, preliminary estimates posit the Free economy in the United States alone could stand around $300 billion when considering both advertising and freemium models. This valuation, however, is likely conservative as it does not account for the far-reaching consequences and creations spun from non-monetary contributions. Even the labor put into web development and creative expression, if converted into standard monetary terms, could easily eclipse $260 billion annually, demonstrating that the Free economy operates on a scale comparable to that of entire nations. Ultimately, this reveals not only a substantial underlying market but also a cultural phenomenon that transcends traditional economic boundaries.

Chapter 11 | ECON 000

In the realm of digital economics, the principles developed by early economists like Antoine Cournot and Joseph Bertrand have undergone significant reinterpretation, particularly as we navigate the complexities of modern markets. Cournot initially focused on production volume as central to competition, suggesting that firms would limit output to maintain high prices. However, after his theories were largely ignored, Bertrand revolutionized the conversation by introducing the concept of pricing as the key to competition, positing that companies would undercut each other until prices reached marginal costs. This led to a foundational principle of economics: in competitive markets, prices tend to fall to the marginal cost of production. 1. The Emergence of Bertrand Competition in Digital Markets: Today’s digital economy epitomizes Bertrand Competition, where marginal costs are approaching zero—particularly for information-based goods. This shift means that "free" is becoming not just a common pricing strategy, but the eventual result of competitive dynamics. As digital replication becomes virtually effortless, businesses that traditionally charged premium prices face immense pressure to either reduce their prices or risk obsolescence. 2. The Role of Market Structure: Despite the near-zero marginal costs in many digital services, notable exceptions like Microsoft challenge the conventional wisdom. Microsoft's success hinged on network effects, where the popularity of Windows and Office allowed it to establish a monopoly and charge higher prices despite low production costs. In essence, monopolies can sustain pricing power as long as they can harness network effects that bind users to their platforms. 3. Shifts in Monopoly and Pricing Power: The dominance of digital platforms such as Google and Facebook suggests that even though they operate in quasi-monopoly situations, the pricing power is limited. These platforms often provide services at little to no cost, generating revenue through scale rather than direct sales. This transformation emphasizes a model where vast user bases allow for lower marginal pricing across the board, benefiting consumers significantly. 4. The Advantages of Increasing Returns: Industries driven by intellectual property often experience increasing returns—where costs decrease while the amount produced increases. This dynamic is apparent in digital markets, where both production and consumption can lead to market dominance. The ability to spread fixed costs over a larger output effectively increases profit margins, defining how businesses operate in this new era. 5. The Concept of Versioning and Free: Economic theories like versioning highlight various price points aimed at different customer bases, allowing for a "free" version in freemium models. Companies can maximize profits by offering basic services for free while charging for premium features. This approach reflects a nuanced understanding of consumer psychology, where pricing strategies are tailored to encourage participation without initial cost barriers. 6. Redefining the Free-Rider Problem: The digital age offers a counter-narrative to the traditional free-rider problem, wherein a small cohort takes on the majority of the workload while others benefit without contributing. Modern platforms thrive with a passive audience, where the vast majority may consume without contributing. This participation fosters a healthier ecosystem, highlighting the incentives that motivate individuals to contribute to communal resources like Wikipedia. In conclusion, the transformation of economic models in the digital age illustrates that traditional theories must adapt to the realities of contemporary markets. The shift towards near-zero marginal costs, the redefining of competition via network effects, and the novel dynamics of free pricing emphasize the need for innovative commercial strategies. Companies are now tasked with navigating these complexities, ensuring they remain competitive and sustainable without defying the gravitational pull of "free." As new markets emerge and existing frameworks evolve, continuous experimentation and creativity will be paramount for success.

Chapter 12 | NONMONETARY ECONOMIES

In the exploration of nonmonetary economies, Chris Anderson delves into the intricate dynamics that arise in a world where traditional currency does not dictate values and exchanges. He references Herbert Simon's assertion from 1971, highlighting a critical truth: in an information-saturated environment, the finite resource becomes human attention. Simon's insights correlate with a foundational economic principle; abundance creates new scarcities, prompting consumers to seek out premium goods in lieu of commodities. For instance, a workplace abundance of free coffee fosters a desire for higher-quality options. Abraham Maslow's famed hierarchy of needs serves as a framework for understanding the evolution of human desires in contexts of abundance. As our basic physical needs are met, individuals ascend to seek higher-order motivations that revolve around social connection, esteem, and ultimately self-actualization, where pursuits such as creativity take center stage. This evolution extends beyond traditional consumer behavior; in the online landscape, the availability of free goods shifts the dynamics, thereby prioritizing attention and reputation over monetary exchange. The emergence of the "attention economy" and "reputation economy" reflects this shift. While attention is coveted in various settings, from television to social media, its quantification online provides a new set of metrics for engagement. Anderson underscores the transition from a monetary economy to one where attention and reputation become the currencies of value. This digital economy is best exemplified by Google’s PageRank algorithm, which evaluates the relevance and influence of websites based on incoming links, effectively turning attention into a measurable asset. As consumers navigate this digital ecosystem, they engage in a marketplace governed by attention and reputation, with various platforms like Facebook and Twitter indicating the richness of these new currencies. Each platform hosts its own form of capital, whether measured in "friends," "followers," or user ratings. The ability to convert this reputation capital into attention—and eventually money—becomes a skill for many, and while the motivations for participation vary, they often include a desire for community involvement, personal growth, and the intrinsic rewards that come from engagement in creative endeavors. Further examination of online gaming reveals specialized economies that reinforce this discussion. Games like Warhammer and Lineage operate under dual currency systems where players can earn virtual currency through gameplay or opt to purchase it, emphasizing the value of time as a crucial factor in the exchange. Game designers must balance these currencies to maintain an engaging experience, as the interplay of time and money drives player interaction. Finally, Anderson turns to the concept of the gift economy, articulated through the pioneering work of sociologist Lewis Hyde. In societies that historically operated outside of formal monetary systems, the establishment of social status emerged from gift-giving practices. In these contexts, reciprocity fosters a mutual obligation and kinship, maintaining a cycle of generosity that diverges from conventional economic transactions. In today’s world, this gift economy is increasingly visible online, manifested in user-generated content and community-driven projects. However, the motivations behind this contribution are multifaceted, often rooted in personal interests and community ties rather than pure altruism. In a landscape characterized by cognitive surplus and unfulfilled emotional needs, individuals find fulfillment through creative expression, reinforcing Maslow's insights that self-actualization plays a crucial role in happiness. Through this expansive examination, Anderson illustrates that in economies where money does not reign supreme, alternative currencies like attention and reputation take the lead, reshaping human interactions and societal value systems in profound ways. The dynamics of the web highlight a vast, interconnected landscape where nonmonetary exchanges flourish, ultimately reshaping the very fabric of our social and economic structures.

Key Point: The Importance of Attention in a Non-Monetary Economy

Critical Interpretation: Imagine waking up each day with the knowledge that your attention, that precious commodity everyone else is vying for, holds tremendous power in a world overflowing with information. As you navigate through your daily life, you begin to prioritize how and where you invest your attention—be it focusing on nurturing relationships, engaging in meaningful conversations, or dedicating time to creative pursuits that ignite your passion. With this understanding, you might find yourself seeking out quality experiences, not just for their material value but for the connections and self-growth they offer. This yearning to devote your attention wisely fosters a deeper sense of fulfillment and a community that thrives on shared interests, reminding you that, in the end, the greatest rewards come not from mere transactions, but from the rich tapestry of human interaction.

Chapter 13 | WASTE IS (SOMETIMES) GOOD

In the modern landscape, the notion of abundance—especially in technology—has transformed how we view and utilize resources. The author presents a compelling case that waste, when seen through the lens of abundance, is not only acceptable but can be beneficial. This perspective shift is crucial for harnessing the full potential of technological advancements. Here’s a structured summary of the key concepts discussed. 1. Redefining Scarcity and Abundance: The author reflects on the outdated mindset around data storage, exemplifying how once perceived scarcity has evolved into an abundance. For instance, while a workplace may restrict storage due to old beliefs in its expense, individuals can easily obtain greater capacity at home. This mismanagement of views on abundance leads to inefficiencies, where time and efforts are wasted on unnecessary constraints rather than exploring available resources. 2. The Cost of Artificial Scarcity: The discussion extends to telecommunications, where companies impose limitations on voicemail storage to save on minimal costs, inadvertently creating a poor customer experience. Such practices illustrate a failure to understand consumer goodwill, which can be more valuable than the operational savings gained through limiting service. 3. Embracing Waste for Innovation: The author draws parallels from nature, pointing out that waste is an inherent part of evolution. Nature deploys strategies that appear wasteful, such as plants scattering seeds with minimal regard for survival, in pursuit of discovering new opportunities. This scattershot approach can be likened to innovative practices in technology and business, where willingness to experiment and accept failures can lead to significant breakthroughs. 4. Cultural Shifts in Consumption: The author reflects on generational changes in media consumption, specifically through platforms like YouTube. Here, content regarded as low-quality or “crap” may actually fulfill particular needs for different audiences. The embrace of diverse, user-generated content allows for niche markets to flourish that traditional media might overlook. The waste of lower-quality videos is justified by their relevance to specific viewers. 5. Abundant Resources and Distribution Models: The author contrasts YouTube with traditional television and Hulu, illustrating how their differing business models reflect scarcity versus abundance approaches. While Hulu capitalizes on known quantities, advertising within established frameworks, YouTube thrives on the unpredictable nature of user-generated content, promoting an environment where all manner of creativity can compete without preconceived constraints of quality. 6. Adapting Management Practices: The author shares their experiences as a magazine editor, navigating the traditional roles of scarcity in print media against the more fluid, abundant online environment. In print, resources are limited, requiring a strict approval hierarchy that stifles creativity and flexibility. Conversely, online publishing welcomes an abundance of voices and ideas, allowing failures to surface while successes inevitably rise to the top based purely on merit. 7. The Imperative of Hybrid Thinking: As organizations grapple with the coexistence of scarcity and abundance, the call to adopt "abundance thinking" becomes pressing. This dual mindset encourages companies to innovate and exploit available resources creatively rather than retreating into outdated frameworks, ultimately fostering a culture where experimentation and flexibility drive progress. In conclusion, understanding and harnessing the concept of abundance—in technology, business, and culture—can lead to greater innovation and satisfaction. As we adapt to this paradigm shift, our ability to embrace waste and think creatively about resources will define the next era of growth and exploration.

Chapter 14 | FREE WORLD

In the realm of cultural transformations propelled by the principles of “free,” China and Brazil emerge as fascinating case studies. During a grand performance in Guangzhou, Taiwan's pop sensation Jolin Tsai took center stage, entertaining a crowd gathered not for a typical concert, but for a corporate sales meeting organized by China Mobile. This spectacle highlights how pop culture in China is molded by the pervasive influence of music piracy, which has led local artists to embrace illegal downloads as a means of expanding their audiences. 1. The Dominance of Piracy in China: In China, piracy has thrived, significantly impacting the music industry. It is estimated that 95% of music consumption occurs through pirated channels. Artists like Xiang Xiang have turned this challenge into an opportunity, utilizing their pirate-generated fame to draw large crowds for live performances and endorsements. This new model sees record companies adapting their strategies; they focus less on traditional album sales and more on concert income and promotional opportunities, thereby redefining their role in the industry. 2. Alternative Business Models: Innovative avenues for monetization, such as sponsorships for events and live performances, are emerging. Companies like MicroMu exemplify this shift by fostering indie artists through brand sponsorships rather than selling music outright. The free access to music not only builds an artist’s fanbase but also allows brands to engage with young consumers, thereby reshaping how music and marketing intersect in this free-for-all landscape. 3. The Paradox of Piracy: The role of piracy extends beyond music; it penetrates various markets, including luxury goods in China. Consumers often prefer original products but also engage with knock-offs due to price restrictions. As a dynamic interplay between original and counterfeit products, piracy can paradoxically enhance brand awareness and demand for authentic goods, illustrating a complex relationship between imitation and original brand equity. 4. The Brazilian Example: In Brazil, the street vendor culture showcases a similar ethos. For instance, the band Banda Calypso, thriving in the "tecnobrega" genre, capitalizes on grassroots marketing facilitated by local vendors selling their music cheaply. This model allows bands to prioritize live performances over album sales, reflecting a shift towards experiential rather than transactional business. 5. Innovative Public Health Policy: The Brazilian government has also applied the principle of free in the public health sector. By leveraging its legal framework to produce generic versions of patented AIDS medications, Brazil successfully reduced costs significantly, fostering a robust local drug industry. This willingness to challenge conventional patent laws demonstrates a commitment to public welfare and adaptation to local needs. 6. Open Source Movement: Brazil's leadership in promoting open-source software complements its push towards free public resources. The government endeavors to replace proprietary software with free alternatives, aiming to democratize access to technology among its populace, exemplifying how open access can benefit an entire nation. These narratives from China and Brazil illuminate that in a world increasingly resistant to traditional business models, the path toward "free" serves not merely as a strategic response to piracy but as a gateway to new opportunities for artists, businesses, and governments alike. The emergence of a free economy reflects a cultural evolution that might redefine industries globally, urging us to reconsider established norms surrounding creativity, ownership, and commerce.

Chapter 15 | IMAGINING ABUNDANCE

In this thought-provoking chapter from Chris Anderson's "Free," the exploration of post-scarcity societies unfolds through the lens of science fiction and philosophical discourse. Anderson emphasizes the unique ability of sci-fi to serve as a rich tapestry for examining the complexities of human existence in an increasingly abundant world. 1. The Creativity of Scarcity: Science fiction operates under specific constraints: while it can stretch the laws of physics, it ultimately reflects human experience. This genre offers a canvas for imagining how humanity might evolve when faced with drastic changes—like an abundance of resources. The dialogue around love and existence in altered circumstances ignites curiosity about human nature. 2. Machines and Abundance: Many narratives engage with the idea of machines producing abundance—think of Star Trek's replicators or WALL-E's robot-run world where laziness reigns. These tales reflect a phenomenon termed "post-scarcity economics," prompting readers to consider the societal shifts that accompany the availability of previously scarce resources. 3. The Downfall of Automation: E.M. Forster’s "The Machine Stops" presents a dystopian vision where humanity becomes overly reliant on a vast Machine providing for all needs. As personal contact declines, creativity stagnates, leading to a collapse when the Machine inevitably fails. This mirrors fears of a future where technology, rather than liberating, could imprison and stifle humanity’s spirit. 4. Dystopia Amid Abundance: Similarly, vintage science fiction reflects concerns regarding the Industrial Revolution's social upheavals, highlighting how technological advancements can lead to structural inequality. In Fritz Lang’s "Metropolis," a stark divide between elite and worker classes illustrates how abundance can co-exist with severe scarcity for many. 5. Fluctuating Utopias: Writers like Arthur C. Clarke envision futures where technology delivers contentment and freedom from death, yet they question the essence of fulfillment beyond material abundance. Clarke’s protagonist sees a contrasting world, suggesting that true meaning often lies outside mechanized comfort and the eternal cycle of existence. 6. Digital Perspectives on Abundance: The arrival of the Internet revolutionizes the concept of abundance, presenting information as virtually limitless. In Cory Doctorow’s narratives, the obsolescence of physical needs ushers in challenges as social capital becomes the new currency, raising questions about purpose and contribution in a world where everything is accessible. 7. Scarcity in Reputation: Doctorow poignantly illustrates that in an abundance-filled society, reputation (or "whuffie") grows in importance, suggesting that human connections and social standing become the new battlegrounds. Neal Stephenson's "The Diamond Age" echoes similar themes of computerized abundance liberating the mind while also questioning the impact on societal motivation. 8. Religious Exaggerations of Abundance: The chapter extends to religious constructs of abundance—depicting paradisiacal afterlives filled with luxury—which serve as a critique of earthly existence. The authors express skepticism about perpetual abundance leading to ennui, reflecting on whether true fulfillment exists outside the struggle for scarcity. 9. Lessons from History: Anderson entrusts readers with the lesson that abundance can profoundly shift societal values, drawing parallels to historical civilizations like Athens and Sparta. These societies, reliant on slave labor, pursued purpose in the arts and military might without losing drive to seek meaning. 10. The Challenge of Imagining Abundance: Ultimately, Anderson concludes that human cognition is often fixated on scarcity, which drives motivation and innovation. The example of the pioneering Iron Bridge reveals a failure to fully grasp the potential of resources in abundance, highlighting the struggle to envision true opportunity in an era of plenty. Anderson's exploration intertwines philosophical inquiry with the narrative power of fiction, creating a compelling discourse that challenges our perceptions of abundance, scarcity, and the human condition. Through imaginative thought experiments, readers are left pondering not just the future but the very essence of what it means to be human in an evolving world.

Key Point: Imagination in the Face of Abundance

Critical Interpretation: As you reflect on the possibilities presented in Chris Anderson's chapter, consider how the creativity of science fiction can inspire you to envision your life in a world overflowing with resources. Rather than succumbing to complacency, let the narratives of post-scarcity societies ignite your imagination. Imagine what you could cultivate—your passions, your relationships, your contributions to society—when the traditional constraints of scarcity are lifted. Embrace the idea that abundance isn't just about having more; it's about fostering a deeper connection to your purpose and exploring new frontiers of creativity and innovation that could emerge from a world where limitations are redefined.

Chapter 16 | “YOU GET WHAT YOU PAY FOR”

In late 2007, Andrew Rosenthal, the editorial page editor of The New York Times, expressed regret over the paper's decision to eliminate the Times Select paywall, arguing that by making their content free online, they devalued journalism. His comments highlight several prevalent beliefs about the concept of "Free," including the perception that no price implies no value and that online information is the only free commodity in a landscape where everything else carries a cost. While there is a kernel of truth in Rosenthal's assertions, they overlook a more nuanced understanding of the economy, particularly in the digital realm. The discourse around "Free" inspires a range of common objections, reflecting deep-seated fears and misconceptions. Here are some of the key objections and their counterarguments: 1. There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch: While it is economically true that nothing is truly free, the cost may be distributed, often in ways that are imperceptible. The marginal costs of digital content are approaching zero, which can justify offering free access while still maintaining underlying economic viability. 2. Free always has hidden costs/Free is a trick: Although there can be strings attached to free offers—such as advertising—these are not inevitable in the digital age. Many contemporary free services can genuinely provide value without hidden costs. 3. The Internet isn’t really free because you’re paying for access: Subscription or service fees are related to internet access rather than the content delivered. Users pay for the carriage, not the content itself, which operates under a separate business model. 4. Free is just about advertising: While advertising-based models have been prevalent, emerging models like freemium—where core services are free and premium features are paid—are demonstrating the viability of diverse revenue streams beyond mere advertising. 5. Free means more ads, and that means less privacy: This concern is often overstated. Many ad-supported platforms have strong privacy measures, and advertising doesn’t inherently equate to a loss of consumer privacy. 6. No cost = no value: The perception that free items lack worth ignores alternative forms of value, such as reputation and attention. Free content can build significant reputational capital, which can be monetized later. 7. Free undermines innovation: Concerns around intellectual property and the remuneration of creators misinterpret the collaborative and open nature of many modern innovations. Sharing and remixing can enhance, rather than stifle, creativity. 8. Depleted resources are the real cost of Free: While free resources can lead to overconsumption and negative externalities, the broader context of digital versus physical goods reveals that digital scarcity operates differently, often without the same detrimental environmental impacts. 9. Free encourages piracy: Piracy occurs when actual costs do not align with the market price. It is not the concept of Free that fosters piracy, but rather the significant disparity between production costs and retail pricing when intellectual property laws are violated. 10. Free breeds a generation that doesn’t value anything: Each generation evolves in response to their economic realities. Young people who are accustomed to free digital goods will not universally expect physical goods to be free; rather, they recognize the different natures and values of digital and physical items. 11. You can’t compete with free: Competing with Free isn’t about matching it dollar for dollar; it involves offering something better or different that provides additional value that consumers are willing to pay for. 12. I gave away my stuff and didn’t make much money: Experiences like those of Steven Poole highlight the necessity of smart business strategies and models rather than merely giving away products in hopes of spontaneous revenue generation. 13. Free is only good if someone else is paying for it: While consumer perceptions can be affected by the absence of a direct price, there are many markets where free offerings maintain a positive reputation without confirming to market expectations. 14. Free drives out professionals in favor of amateurs: The rise of amateur content does not signify the death of professionals. Instead, it necessitates a reinvention of roles, leading to new opportunities for professionals in ways that leverage their unique talents. Looking to the future, the principles of abundance thinking suggest that as digital content becomes increasingly free, businesses must innovate and redefine their models to extract value rather than attempt to compete with zero-cost alternatives. The evolution of the internet and its economic implications signals that while Free may represent a compelling model, it necessitates a balance with monetization strategies suited for a rapidly changing landscape.