Last updated on 2025/06/23

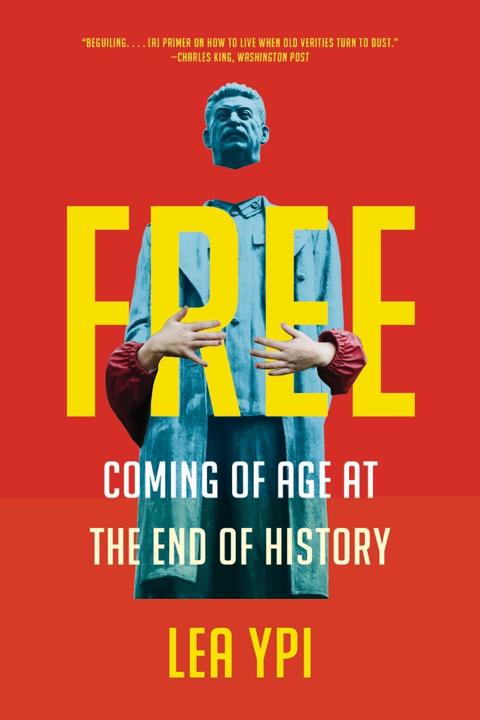

Free By Lea Ypi Summary

Lea Ypi

Exploring freedom and identity in a changing world.

Last updated on 2025/06/23

Free By Lea Ypi Summary

Lea Ypi

Exploring freedom and identity in a changing world.

Description

How many pages in Free By Lea Ypi?

100 pages

What is the release date for Free By Lea Ypi?

In "Free," Lea Ypi deftly intertwines her personal narrative with profound political inquiry, inviting readers to reconsider the very notion of freedom as she reflects on her upbringing in Albania during the tumultuous years of communism and its painful aftermath. Through a lens that combines memoir and philosophy, Ypi explores the complex relationship between individual liberty and collective identity, illuminating how our definitions of freedom are shaped not just by personal choice but also by the political landscapes we navigate. With striking honesty and intellectual rigor, she challenges us to think critically about what it means to be free in a world still grappling with the shadows of its past, making "Free" a compelling read for anyone seeking to understand the intricate dance between personal autonomy and societal expectation.

Author Lea Ypi

Lea Ypi is a prominent Albanian-Australian political philosopher and author, renowned for her incisive analyses of freedom, democracy, and political theory. Born and raised in communist Albania, Ypi's early experiences of political oppression and the subsequent transition to democracy profoundly shape her intellectual pursuits and writings. She is a professor at the London School of Economics, where she explores the intersections of liberalism, normative political theory, and the ethical dimensions of political life. Her groundbreaking work, 'Free,' reflects her commitment to examining the complexities of freedom in both personal and societal contexts, offering fresh insights into the nature of liberty, individual agency, and collective responsibility.

Free By Lea Ypi Summary |Free PDF Download

Free By Lea Ypi

Chapter 1 | 1. Stalin

In a poignant and nuanced reflection on the concept of freedom, Lea Ypi recounts a moment from her childhood that incites her inquiry into the nature of liberty amidst political turmoil. The narrative begins with Ypi's encounter with a statue of Stalin, a figure she was taught to revere in the context of Soviet ideology. Through her teacher Nora's lessons, she learns to focus on Stalin's greatness rather than his physical stature, often described as short. Instead, Ypi describes him as a giant, pointing out Stalin's friendly demeanor expressed through his eyes, which held more significance than his porcelain visage. As Ypi recalls her yearnings for assurance, her youthful innocence at the time is palpable; she grapples with the contrasting realities of her childhood adventures with friends and the turmoil marking her society. On an intriguing December day, she finds herself inadvertently engulfed in a protest while navigating her way home after cleaning duties with her friend Elona. While she has enjoyed a seemingly carefree existence, the protest symbolizes a sudden confrontation with the question of freedom—one she had not previously pondered deeply. Caught up in the protest throng, she feels a mix of excitement and dread, seeking refuge against the statue of Stalin, which becomes a representation of her conflicted understanding of freedom. This misunderstanding is illustrated by her earlier choices—whether to engage in trivial games with Elona or join the crowd anticipating biscuits from the local workshop—all of which reflect the weight of decisions and their consequences. Ypi contextualizes her encounters with her worldview shaped by socialist sentiments, familial directives, and the societal pressure to conform. 1. Ypi expresses a feeling of overwhelming freedom, explaining how her childhood choices felt burdensome, as they came loaded with implications. She juxtaposes the innocent joy of choosing games and snacks against the weightier political environment surrounding her. 2. The narrative shifts from personal experiences to a broader commentary on societal events, including references to embassy protests and political dissent in Albania during tumultuous times. Ypi reflects on her understanding of freedom in this political landscape, challenging the perception propagated by her educators—freedom as inherent within their socialist existence. 3. The climax rests in her encounter with the vandalized statue of Stalin, representing her shift from blind adoration to a deeper contemplation about symbols of power and authority. The beheaded statue evokes feelings of chaos and uncertainty, mirroring the inner conflict regarding the legitimacy of the protesters’ call for “freedom and democracy.” 4. In a compelling conclusion, Ypi seeks clarity and courage, ultimately choosing to run home. This act symbolizes a reclaiming of her agency amidst confusion and fear, signifying her journey towards understanding the complexities of freedom—both in her personal life and within the fractured realities of her society. Through Ypi's narrative, the intertwining of childhood innocence, societal expectations, and the struggle for ideological clarity emerges as a powerful discourse on the essence and implications of freedom, demonstrating how the personal voyages of youth brush against the larger currents of historical change. The contrasting themes of innocence and political awareness underscore the complexities faced by individuals navigating their identities within shifting sociopolitical landscapes.

Chapter 2 | 2. The Other Ypi

In Chapter 2 of "Free" by Lea Ypi, we encounter a vivid recollection of moments in the author's childhood that intricately intertwine personal dynamics and socio-political realities. The chapter begins with a dramatic scene where Nini, the author’s grandmother, is anxiously awaiting her arrival home from school, expressing concern over the author’s tardiness. Her anger, however, is not just a reflection of worry but a method of instilling a sense of responsibility by reminding Ypi of the broader implications her actions could have on others. 1. The interaction with family becomes crucial as the author navigates through feelings of confusion and frustration at home, primarily stemming from their politicized environment. The author’s father, who enters the scene after the grandmother, is characterized by his anxiety, indicative of a complex familial backdrop. His attempts to explain the situation surrounding a protest evoke a contrast between personal and political worlds, reflecting how different family members engage—or disengage—with politics. 2. The author’s mother, often indifferent towards political matters, channels her own frustrations into work around the house. Her sweeping actions reveal an underlying tension that mirrors the societal movements outside, illustrating how domestic life is enmeshed with larger political narratives. In her reaction to the idea of hooligans versus protesters, Ypi’s mother demonstrates a reluctance to engage with the contentious political atmosphere, distancing her family from the unfolding protests and framing family discussions within mundane, domestic contexts. 3. A pivotal moment occurs when Ypi grapples with a classroom assignment that alludes to a historical figure sharing her surname, Xhaferr Ypi, a national traitor associated with Albania’s fascist past. This connection ignites a profound identity crisis for the author, who feels the weight of historical narratives and familial legacies pressing upon her. Unlike her peers, who recount heroic family stories of resistance against fascism, Ypi's attempts to connect with her own familial past are thwarted by the shadow of the infamous figure, leading to feelings of alienation and insecurity. 4. The narrative explores themes of legacy, identity, and the impact of history on personal life, as Ypi confronts the duality of her existence—one life inside her family and another in the public domain. The frustrations spilling over contribute to her questioning the value of freedom and how it is represented in her household versus the outside world. 5. In a climactic moment of defiance against her familial norms, Ypi announces her intention to skip school, a declaration met with familiar resistance from her family. Yet, unlike previous exchanges, it becomes the catalyst which prompts an unexpected dialogue, revealing deeper political divides within the family. Ypi's mother breaks her usual silence on political matters to engage in a controversial defense of the compromised figure in their family history—pointed revelations that leave Ypi grappling with the implications of her mother’s statements, as well as the complexity surrounding collective memories and national history. 6. The latter part of the chapter paints a picture of societal unrest with burgeoning protests calling for democracy and political plurality, challenging the one-party system. This backdrop amplifies the author’s internal conflict as she perceives the lack of shared enthusiasm for these movements within her family. As her innocent worldview begins to fracture, Ypi embarks on a deeper exploration of identity, questioning the truths of her upbringing, her family's history, and the nature of freedom as she witnesses social change unfold. By the end of the chapter, Ypi realizes that her childhood innocence is slipping away. The barriers between her personal experiences and the external socio-political climate begin to dissolve, leaving her with an overwhelming sense of curiosity and a need to reevaluate her understanding of freedom, family, and self. This culminates in a recognition that her life narrative is not merely about recounting events but is a continuous search for the most pressing questions that challenge her understanding of her place in a dynamic, often contradictory world.

Key Point: Understanding the Complexity of Freedom

Critical Interpretation: As you reflect on your own life, consider the pivotal moments that shape your understanding of freedom and identity. Much like Ypi, you may find yourself caught between familial expectations and the notable events of the world around you. This chapter invites you to explore how the responsibilities you bear, influenced by both personal and political realities, shape your perception of freedom. Remember that freedom is not simply about absence from constraints; it involves a nuanced engagement with your surroundings, questioning the legacies you inherit and how they forge your own identity. As you navigate your relationships and societal pressures, embrace the complexities and contradictions inherent in your quest for autonomy, inspiring you to carve out a space where your voice can be heard amidst the cacophony of history.

Chapter 3 | 3. 471: A Brief Biography

Chapter 3 of "Free" by Lea Ypi provides an introspective glimpse into the author's family background, particularly focusing on the complex narratives of her parents’ lives and how these shaped her own identity. The chapter opens with a reflection on the concept of "intellectuals," as referenced by the author's teacher and redefined by her father, suggesting that everyone, regardless of their educational achievements, belongs to the working class. This theme of biography, which permeates the text, underlines how personal histories are intricately tied to one's social standing and societal expectations. 1. Lea Ypi recounts her father's experience, marked by academic prowess yet hampered by political constraints. Despite his exceptional talent in the sciences, prevailing societal norms and personal histories relegated him to forestry studies instead of his desired math pursuits. His struggles, including asthma and familial discord, encapsulate the broader narrative of individuals navigating their identities within a restrictive socio-political landscape. The significance of "biography" emerges as a dual-edged sword—both a source of identity and a constraint. 2. The author contrasts her father's educational limitations with her mother's literary inclinations and passion for music. Her mother’s academic journey reflects the compromises faced by many—studying mathematics when her passions lay elsewhere—driven by financial necessity. Yet, even amidst adversity, she thrived as the national chess champion, emphasizing personal agency through skill rather than solely relying on her background. Her mother’s childhood, fraught with hardships, is peppered with moments of love and creativity, particularly her bond with Hysen, which enriches Ypi's understanding of familial dynamics. 3. Ypi further explores her mother’s resilience through a poignant narrative about her own precarious birth under challenging circumstances. Born with a low chance of survival, she was initially identified by her hospital number, 471, embodying the hope and despair that colored her early existence. The chapter illustrates the depth of familial love and effort, as both her parents and grandmother dedicated themselves tirelessly to ensure her survival during the early months of her life. Ypi's premature arrival serves as a metaphor for the unpredictable nature of existence, intertwined with the familial "biography" that held immense weight in her upbringing. 4. The narrative shifts to Ypi's development and changing perceptions of health and survival. The rare illnesses she experienced later in life led her to romanticize disease, viewing sickness as a gateway to sympathy and attention. This nuanced understanding of her early struggles fosters introspection about her unique place in her family’s biography, distinct yet interconnected with others. 5. The chapter culminates in a philosophical reflection on the nature of choices and freedom. Drawing lessons from her grandmother’s teachings, Ypi expresses a belief in the ultimate responsibility one holds for their fate. While "biography" outlines the limitations imposed by context, understanding these boundaries allows for personal freedom and the ability to navigate one's choices. The interplay between success and failure, much like strategic moves in a chess game, illustrates that despite the constraints of biography, agency persists in crafting a personal narrative. Through vivid storytelling and intricate familial portraits, Chapter 3 of "Free" encapsulates themes of struggle, identity, and choice, inviting readers to reflect on their own biographies and the weight these narratives carry in shaping their destinies.

Chapter 4 | 4. Uncle Enver Has Left Us for Ever

On April 11, 1985, a deeply emotional event struck the nursery where young children were gathered under the guidance of their teacher, Flora. She solemnly announced the death of Uncle Enver, a significant figure in their lives, eliciting a mix of confusion and somber reverence among the children. Flora urged them to recognize that while Uncle Enver had passed away, his legacy and the values of the Party would endure. Through this announcement, the children were thrust into a complex conversation about death and what it means, as they grappled with the loss of a figure who represented hope and guidance in their community. 1. The children explored the nature of death through a series of discussions, sharing their beliefs and fears. Marsida, one of the children, introduced the idea that death might not be the absolute end, suggesting that some essence of a person continues on after they depart. This notion sparked debate, with some children arguing that when one dies, they cannot move or exist anywhere else, while others reminisced about their experiences with death, recalling coffins and graves. The conversation mixed naivety with revelations, as the children attempted to articulate their understanding within the parameters set by their upbringing. 2. Conversations about life, death, and religious beliefs intertwined as their education progressed. Teacher Nora later deepened their understanding by contrasting religious traditions and how society had evolved past them, asserting that belief in God had been a tool used by the rich to ensure control over the poor. She emphasized that the clarity brought by the Party's ideology liberates people from superstitions, reinforcing the idea that one life is all they have and that it is the work they do that will live on. This assertion that they should not hope for an afterlife resonated powerfully with them, shaping their perceptions of reality and mortality. 3. The internalization of Teacher Nora's teachings affected how the children viewed their culture and traditions. The children learned to associate the Party's ideology with liberation from religious confines, leaving little room for beliefs in a higher power or continuation after death. This transition from a belief-based worldview to one strictly grounded in observable reality and the legacy of work symbolized a broader societal development at that time. The Party became the new unwavering power, a guiding force as significant as previously held religious beliefs. 4. The impact of Uncle Enver's death became palpable during the televised funeral, where the national mourning was palpable. The solemnity of the funeral procession contrasted with mundane family interactions at home. While the commentator valorized Uncle Enver's contributions to Albania and the Party, the family's conversation veered into a lighthearted debate over the funeral music, illustrating how deeply ingrained political and cultural sentiments can evoke varied responses. 5. Through cumulative experiences, such as witnessing the funeral and grappling with personal grief, the narrator's attachment to Uncle Enver heightened. A desire for a photo to commemorate his existence highlighted how children both idolize and grapple with loss. It further underscored a sense of neglect felt when familial promises regarding the memorialization of Enver remained unfulfilled, evoking feelings of loneliness and disconnection from the collective grief surrounding them. A conversation with a beloved grandparent further complicated their understanding of love and loyalty to figures like Uncle Enver, juxtaposing personal connections with nationalistic devotion. As time progressed, these children, shaped by loss and the dominant ideology of their environment, navigated their formative years amidst an evolving landscape of beliefs, childhood innocence, and adult realities. Their reflections and experiences encapsulated the cultural and social intricacies of a nation in transition while revealing the delicate balance between personal and collective identity that defined their childhoods.

Key Point: Legacy of Values

Critical Interpretation: Reflecting on the discussions among the children about death and the legacy attached to Uncle Enver, take a moment to consider how your own values can live on long after you are gone. Just as the children were urged to understand that while Uncle Enver may have died, his influence and the ideals of the Party would continue to guide their futures, so too can you aspire to leave a meaningful mark on the world. Each choice you make today, every act of kindness, and every value you instill in those around you has the power to resonate beyond your lifetime. Imagine the inspiration you can ignite in others and how your legacy can become a force for good, shaping lives and communities in ways you might not even foresee.

Chapter 5 | 5. Coca Cola Cans

In the narrative of Chapter 5 from "Free" by Lea Ypi, the author reflects on the complexities of social norms and personal relationships shaped by material symbols in a community. At the heart of the narrative is the story of a Coca Cola can, which serves as a vessel for exploring themes of trust, social hierarchy, and the intricacies of growing up within a society bound by rules that often require navigating between adherence and rebellion. 1. Understanding Social Rules and Adaptations: The author illustrates that individuals, including her family, grapple with various societal expectations and rules, determining which are rigid and which can be bent or broken over time. This social education encompasses everyday activities, such as the communal experience of grocery shopping, where queuing conventions reflect deeper societal lessons on respect, patience, and community dynamics. The playful loopholes within the queuing system signify a nuanced understanding that emerges from growing up—where the mastery of knowing when to follow or defy rules becomes a vital social skill. 2. Community Relationships and Personal Connections: The narrative shifts focus to the author's relationship with her neighbors, the Papas, who play a significant role in her family's life. The bond formed between families is tested when a trivial possession—the Coca Cola can—leads to an escalating conflict. The can symbolizes status and envy within their small community, and its loss triggers a fight that disrupts the previously strong ties of friendship. The intensity of the conflict serves to illuminate how material possessions can fracture relationships, revealing the fragility of human connections amidst the backdrop of shared histories and communal life. 3. Navigating Conflict and Reconciliation: The escalating feud over the Coca Cola can embodies the deeper issues of respect and dignity in mental and material terms. The author observes that despite the absurdity of the conflict, the arguments reflect buried sentiments and a longing for acknowledgment and companionship. The resolve comes through innocent actions—a child’s deliberate ploy to foster reconciliation by invoking the community's sense of concern. This deft approach illustrates the innocence of youth, exemplified when the author climbs the Papas' fig tree, eventually prompting the families to re-evaluate their dispute. 4. Maturation and Social Integration: Ypi candidly explores her internal journey to grasp the delicate balance of societal expectations and familial ties. Her experiences provide a backdrop for the difficult lessons about loyalty, identity, and social allegiance as she must navigate between her familial loyalty and the expectations of her community regarding political adherence. The conversation between Mihal and the child underscores a pivotal moment of maturity, illustrating how societal values are internalized, often at the expense of critical thinking about authority and family. 5. Reemergence of Trust and Shared Values: As the narrative progresses, reconciliation becomes possible not just through acknowledgment of past grievances but through the re-establishment of mutual respect and shared memories. The families’ eventual return to harmonious interactions hints at a larger commentary on resilience and the innate human need for connectivity amidst societal pressures. The community's laughter and shared experiences indicate that while material possessions like the Coca Cola can can create divisions, ultimately, it is the bonds of mutual support and understanding that restore harmony—emphasizing the underlying message of social cohesion and collective identity. In conclusion, Chapter 5 poignantly encapsulates the intertwined threads of childhood innocence, social order, and the impact of seemingly trivial objects on relationships within a community. Through her recollections, Lea Ypi invites readers to reflect on the formative moments that shape our understanding of relationships, authority, and the complexities of growing up in a society marked by restrictions—both imposed and self-regulated.

Chapter 6 | 6. Comrade Mamuazel

In an evocative tale set in a seemingly ordinary yet deeply complex childhood, the narrator recounts a dramatic encounter with a local bully named Flamur, who embodies the more brutal aspects of the environment in which they grew up. The interaction begins with Flamur, wielding a cane and demanding a specific type of gum, leading to a wider commentary on the power dynamics of childhood interactions steeped in symbolic gestures of control and resistance. A hallmark of this narrative is the personal reference to children’s hierarchical relationships in their neighborhood, juxtaposed against a backdrop of political allegory. 1. Flamur stands as a pivotal figure representing the abusive power dynamics pervasive in the community. He routinely exerts his dominance over peers by enforcing arbitrary rules and bullying, particularly targeting those who appear different or vulnerable. The narrator’s hesitance to cry hints at the deep-seated fear of showing weakness, illustrating the harsh social landscape shaped by Flamur's unpredictable tyranny. His reign is marked by a savage mix of childish innocence and nascent brutality, reflecting larger themes of authority and submission that echo through the adult world. 2. A deeper narrative arises regarding familial relationships and the nuances of upbringing. The narrator's family outlets a contrasting disposition—the absence of physical punishment and the cultivation of a clearer understanding of authority. The narrative reveals a journey of self-discovery, where the narrator grapples with their identity in a potentially oppressive environment. The unique familial support structure, juxtaposed with Flamur's turbulent backdrop, paves the path for the exploration of emotional complexity and the internalized conflicts surrounding accepted behaviors. 3. The narrator's reflections extend into the broader sociopolitical context. Musing on their unique upbringing, particularly regarding language and identity, reveals a strain between cultural heritage and personal experience. The duality of speaking French versus Albanian becomes a symbol of separation, influencing interactions with peers, and magnifying feelings of otherness. The longing for shared culture and the associated frustrations shed light on the battle between an inherited legacy and the immediate need for acceptance among peers. 4. In moments that touch upon the significance of education, the decision for the narrator to begin school becomes a cornerstone of self-assertion against external pressures. A pivotal meeting with the Party officials encapsulates the systemic nature of education within the communist regime. The experience is portrayed with humor and tension alike, culminating in an understanding that transcends mere compliance with authority. The sense of pride in academic accomplishments intertwines with the weight of familial expectations, prompting a tumultuous embrace of burgeoning identity. 5. The development of personal agency culminates in the conscious decision of the narrator to reject the imposed language of French amidst the psychological grip of oppression. This act of defiance against the norms crafted by Flamur and learned from parental expectation points to a significant turning point in personal empowerment. The shift towards embracing a more culturally accepted narrative reflects the tension between self-identity and societal expectations, creating a rich tapestry of growth. Enveloped in these interactions are broader insights into sociopolitical dynamics, emotional struggles, childhood innocence, and the nuances of cultural identity, laid bare through the lens of a young girl navigating the implications of power, language, and belonging. Ultimately, this chapter serves as a vivid reflection on the complexities of childhood, drawing parallels between personal and political narratives that shape individual identity.

Chapter 7 | 7. They Smell of Sun Cream

Chapter 7 of Lea Ypi's "Free" delves into the complex interplay between environment, culture, and media as perceived through the lens of childhood. The narrative is set against the backdrop of Dajti, a mountain that symbolizes both physical and psychological distance. Dajti looms large in the protagonist's consciousness, representing a source of external information and a gateway to thoughts of freedom, lawlessness, and imagination. The family's attempts to connect with the world outside through the television signal illustrate a profound longing for knowledge and a connection to broader experiences. 1. The protagonist recounts the comedic struggles of his father in trying to secure a reliable television signal from Dajti and Direkti, the two competing sources of televised information. Each signal reflects a different aspect of their lives: Dajti, steadfast but limited, and Direkti, alluring yet unpredictable. The act of adjusting the antenna becomes a metaphor for their fleeting grasp on outside information and the emotional investment that comes with it. 2. The chapter describes their limited television programming, laden with competition between family preferences and national sports broadcasts, culminating in a depiction of how scarce media shaped their understanding of the world. The introduction of "Foreign Languages at Home" enriches their lives, allowing them imaginative glimpses into other cultures through educational television. This program not only teaches languages but also exposes the children to the very different lifestyles of people in the West, igniting curiosity and sometimes envy. 3. The children participate in thought-provoking discussions inspired by snippets from the language broadcasts, culminating in reflections on consumerism, social structures, and the perplexities of a Western lifestyle. Their questioning of things such as grocery labels and shopping trolleys illustrates a deep-seated curiosity about a world that is vastly different yet tantalizingly close. This also serves to contrast their own realities governed by limited choices and enforced regulations. 4. Interestingly, encounters with tourist children become critical moments of reflection for the protagonist. The distinctions between their lives are palpable: something as simple as the scent of sun cream becomes an emblem of an unreachable world, igniting feelings of curiosity, envy, and pitiful misunderstanding within the protagonist. As they watch tourists with their luxurious toys and carefree whims, the children grapple with questions about privilege, freedom, and happiness. 5. The story weaves through the internal conflicts stirred by comparisons to Western children, emphasizing the narrator's simultaneous longing for connection and a sense of superiority in their own system. Teacher Nora's lessons on capitalism expose the moral dilemmas and inequality that characterize life outside their own, further complicating their understanding of freedom and personal agency. 6. The protagonist's eventual encounter with a group of French tourists culminates in a moment of unexpected self-awareness, as they momentarily bask in the attention of the tourists and question their own identity against the backdrop of a foreign language and culture. The experience highlights the intricate dynamics of power, perception, and belonging in a world so close yet so unattainable. Ypi’s narrative confronts themes of freedom—both in its elusiveness and its interpretation—within a personal and sociopolitical context. The complexities and contradictions inherent in the protagonist’s upbringing are poignantly captured through the lens of childhood curiosity, illustrating a vivid tapestry of longing for freedom, connection, and the haunting specter of inequality.

Chapter 8 | 8. Brigatista

Upon returning home from a trip to the island of Lezhë, Lea reflects on a shift in her feelings, having been both annoyed and amused by the tourists' ignorance of her culture. This amusing realization carries a sense of confidence, as if she had passed an unspoken test of knowledge. During dinner, as she shares her experience, her grandmother unexpectedly retrieves a vintage postcard from the past — a token of a time when her grandfather was celebrated for studying in France. The card, bearing the iconic image of the Eiffel Tower, sparks a conversation about the intriguing link between her grandfather's education and a broader historical context involving anti-fascism and international resistance movements. 1. Lea learns that her grandfather, connected to her family history, had aspirations of fighting fascism, a fact that ignites her curiosity and excitement. She finds herself eager to share this newfound heritage with her schoolmates. However, the narrative leads to revelations about her grandfather's return to Albania due to familial pressure, which perplexes her. The conversation reveals a generational gap in understanding political ideologies, with Lea grappling to comprehend her family's past and differing opinions on activism. 2. As Lea's grandmother recounts her grandfather's endeavors, the discussion transitions to the French Revolution. Her grandmother's unwavering belief that it represents freedom and enlightenment stirs both admiration and skepticism in Lea’s father. While his respect for revolutionary ideals is evident, he criticizes the ultimate failure of these revolutions to achieve true equality, particularly in light of capitalism's persistent inequalities. This divergence highlights the family's complex relationship with history and its significance in shaping their views on freedom. 3. The conversations describe familial dynamics shaped by contrasting attitudes toward money and social responsibility. Lea’s mother epitomizes frugality and a capitalist mindset, while her father embodies a disdain for material wealth, suggesting that wealth generates power inequalities. His philosophy celebrates sharing and generosity, as seen through their interactions with a beggar named Ziku, whom he openly supports despite his wife’s more pragmatic approach. The tension between economic values creates an engaging exploration of how personal philosophies intersect with broader social principles. 4. Lea’s father’s radical inclinations inspire further scrutiny into revolutionary movements and the moral dilemmas surrounding them. He romanticizes revolutionary figures and their struggles against oppressive regimes while simultaneously condemning violence. This generates a complexity in his views, mixing admiration with a profound recognition of his limitations within a rigid political structure. His struggles to articulate a coherent vision of freedom reveal a broader commentary on the inherent challenges of advocating for transformative societal change. Ultimately, the narrative weaves together personal history, political inquiry, familial tensions, and reflections on freedom, creating a rich tapestry of ideas that resonate within the framework of Lea's upbringing and her evolving understanding of the world around her. Through conversations with family members, she navigates the legacies of past revolutions, the interplay of personal and collective identities, and the continuous challenge of defining what freedom truly means in the context of her heritage and society.

Chapter 9 | 9. Ahmet Got His Degree

In late September 1989, a new boy named Erion entered the narrator's class, carrying the heavy weight of family ties and messages from the past. Upon introducing himself, Erion revealed that he was the narrator's cousin and shared news about his grandfather, Ahmet, who had recently graduated. Ahmet’s return sparked a family discussion filled with conflicting emotions; the narrator’s mother expressed caution, while the grandmother contemplated a visit. Despite initial hesitation, the family decided to celebrate this reunion, purchasing a box of Turkish delight to offer to Ahmet. Ahmet began regularly visiting their home, bringing gifts and sharing stories. His slow demeanor and the remnants of a challenging past—expressed in the trembling of his hands and the missing thumb on his right hand—served as reminders of experiences that shaped him. However, these visits, initially received with joy, soon became a source of concern as they coincided with changes in the narrator’s father’s work situation, leading to a cautious withdrawal from connecting with Ahmet. As the family grappled with their shifting fortunes, higher education appeared as a singular topic of fascination in their conversations. The significance of graduating from university became intertwined with their identities and aspirations, often serving as a focal point of pride during social gatherings. Relatives exchanged stories of academic achievements, drawing comparisons between the perceived merits of different degrees and institutions. Within this context, the narrator began piecing together a complex mosaic of knowledge and family lore, marked by the mysteries surrounding her grandfather's own educational journey and the notorious teacher, Haki, who embodied both the challenges and the complexities of academia. The narrative delves into the struggles and triumphs of individuals defined by their educational experiences. The story of Ahmet's struggles with reintegration into a world that had changed dramatically during his absence, as well as their family's collective obsession with academic success, reveals the complicated relationship between personal achievement and social expectation. The narrator's own burgeoning understanding of these dynamics suggests that her family's stories held truths waiting to be uncovered, yet those truths often remained shrouded in the nuances of familial loyalty and societal pressures. Throughout this journey, the narrator reflects upon her earlier naive acceptance of her family's narrative, realizing that understanding the complexities of education, societal roles, and family connections requires more than passive listening; it demands inquisitiveness and courage to seek the truth. Ultimately, the chapter lays bare a deeper insight into how education, familial bonds, and the passage of time interweave to form the tapestry of identity, anchoring the protagonist within a web of history that she is just beginning to comprehend.

Chapter 10 | 10. The End of History

In the reflections of Lea Ypi in the chapter titled "The End of History," we revisit the complexities and contradictions of identity and ideological evolution amid a changing political landscape. The narrative unfolds through a personal lens, juxtaposing moments of innocence from childhood with harsh realities of a society transitioning from socialism to pluricultural political engagement. 1. The Last May Day Parade: Ypi recalls the vibrant May Day celebrations in 1990, a day steeped in nostalgia, marked by joy, family interactions, and social unity, despite the looming economic distress and empty store shelves. This dichotomy highlights an instinctual yearning for a past perceived as simpler and happier, even as the foundation of that happiness was crumbling. 2. The Culture of Competition: Ypi’s experiences at a Pioneers' camp during the summer reveal the ingrained culture of competition as a substitute for the values of solidarity intended by socialism. As children competed for medals and recognition, the very ideals the camp was meant to instill began to dissolve, illustrating the tension between collective progress and individual ambition. 3. Awakening to Historical Realities: A pivotal shift occurs when the veil of optimism surrounding the Party's ideals is lifted, exposing Ypi to the darker truths of her family's history and the societal structures around her. Conversations with her parents disclose the harsh familial legacy of oppression and betrayal under socialism, revealing a shared history of imprisonment disguised as education. 4. The Disillusionment of Ideals: The transition to a multi-party state heralds a time of introspection and confusion for Ypi. The collective demand for change flips the narrative she had been taught—transforming the Party from a symbol of hope into one of tyranny. This sudden ideological reversal leaves her grappling with questions of identity, belonging, and the integrity of her upbringing. 5. The Weight of Heritage: The exploration of her family's past uncovers a complex tapestry of pain, struggle, and resilience. It is a history layered with the sacrifices and compromises made in the name of survival, prompting Ypi to confront the ethical implications of her lineage and the expectations tied to her identity as a descendant of political figures. 6. The Illusion of Freedom: As the political landscape shifts, Ypi notes how the language of freedom permeates the conversation yet becomes devoid of substance. She describes this newfound freedom as a cold dish served without warmth—hungry citizens grasping for meaning within a narrative that drastically reshaped their reality. 7. The Ambiguity of the Transition: Ypi reflects on the ambiguous emotions surrounding the collapse of socialism and the rise of new democratic ideals. The past and future seem irreconcilable, where shared histories blur lines between oppressor and oppressed, casting doubt on personal narratives and social roles amidst drastic change. Through Ypi's poignant accounts, readers are invited to witness a young girl’s transformation against the backdrop of historical upheaval, illustrating the perpetual tension between hope and despair, freedom and oppression, identity and ideology. It encapsulates the struggle to understand how personal experiences are interwoven with the broader currents of societal change, resulting in a profound reevaluation of one’s beliefs and heritage in the face of history's relentless march.

Key Point: The Illusion of Freedom

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing at a crossroads where the very notion of freedom is presented to you, yet the warmth and substance you crave are absent. This chapter invites you to consider how often we chase after the term 'freedom', only to find it a hollow promise, much like a cold dish served without flavor. Let this realization inspire you to seek a deeper, more meaningful understanding of freedom in your own life. Are you simply accepting what society defines as freedom, or are you daring to explore what true freedom means to you? As you navigate through life, remember that freedom is more than just the absence of constraints; it is the vibrant pursuit of purpose, identity, and belonging. Embrace the complexities of your own journey towards freedom—understanding that it is nuanced, and requires introspection and authenticity.

Chapter 11 | 11. Grey Socks

In the days leading up to the much-anticipated free elections, a young girl named Elona initiates a conversation about family beliefs and political opinions at school. During this exchange, she expresses that her father believes the ruling Party was wrong about many things, a sentiment echoed by Ypi, who grapples with faith and the newly emerging concept of pluralism. As the children discuss beliefs, the uncertainty of religious existence and the impact of their families' past on their current views on socialism and democracy becomes apparent. Amidst conversations of faith and politics, the narrative reflects on the emotional and psychological toll uncertainty brings to their families. Elona's father, once a committed worker and believer in socialism, now exhibits signs of despair and frustration. The changing social landscape challenges their previously held beliefs as they analyze the ramifications of their new political environment. They realize that past promises of progress and freedom remain unfulfilled, and the idealistic pursuits of their parents have disintegrated into bitterness over lost hope. Ypi recalls the eerie calm of a voting morning that diverges starkly from his previous experiences. This time, the family lingers in bed, hesitant and uncertain, seemingly reluctant to engage with the very freedom they once craved. This moment contrasts sharply with their regimented, early-morning routines of the past, which were characterized by an enforced obedience to a flawed electoral process. As they finally muster the courage to venture out, they encounter remnants of the past: lingering loyalty to the Party and nostalgia for a system that had both oppressed and defined them. Yet, the atmosphere is infused with hope as new symbols of democracy begin to emerge. Young Ypi observes the symbolism of a new "V" gesture and begins to feel its power. However, this liberating atmosphere soon gives way to a painful reality when the results of the election reveal the enduring influence of the Party. The electoral outcome sparks a wave of protests, highlighting the stark divide between those seeking change and those clinging to a bygone era. As chaos unfolds across the streets, young Ypi contemplates the unpredictable nature of their newfound freedoms and the price that democracy often demands. In the aftermath, a transition to liberalism leads to rising unrest, rooted in economic struggles and a growing sense of betrayal among the populace. The introduction of severe economic reforms dubbed "shock therapy" symbolizes both a desperate remedy for a fractured economy and the harsh realities of immediate change. Numerous protests erupt, revealing bloodshed that stains the quest for democracy, and Ypi's family witnesses the intersection of idealism and the far-reaching implications of their choices. Amidst this confusion, the arrival of an old acquaintance, Bashkim Spahia, offers comic relief through his theatrical need for grey socks, a catalyst for his political aspirations. His desperation highlights the absurdity that sometimes accompanies the political landscape. As Bashkim eventually dons the woolen socks that became a symbol of Ypi's family’s support, he evolves from a local doctor to a charismatic politician entrenched in a world rife with contradiction. Through Ypi's eyes, the complex fabric of change is woven; the loss of family ideals in the face of political upheaval juxtaposes the hope for a new beginning and the sobering reality of democratic participation. As Ypi observes Bashkim's transformation into a successful figure within the new order, the narrative closes by acknowledging the unforgiving nature of change, marked by both humor and poignancy, leaving lingering questions about the true cost of freedom and the integrity of the individuals who pursue it.

Chapter 12 | 12. A Letter from Athens

In January 1991, a letter from Athens arrived at my grandmother’s home, signed by Katerina Stamatis, a name unfamiliar to us. Intrigued, we gathered in our neighbor Donika's living room to inspect the letter, despite the fact that Donika could not read Greek. Tension filled the air as Donika discovered that the letter had been opened multiple times, prompting discussions about the importance of privacy and the future of the postal service in Albania. My mother asserted that privacy was a right, which ignited a debate about the need for the post office to be privatized. As my grandmother read the letter aloud, Katerina introduced herself as the daughter of a past business associate of my great-grandfather. She sought to help my grandmother reclaim properties lost after World War II due to political upheaval. This revelation reignited memories for my grandmother, who had last seen her father in 1941, and had been unaware of his death until years later. Katerina’s letter was more than an outreach; it was a potential ticket to the past that offered hope in the context of financial troubles my family was experiencing. My parents and grandmother examined whether she could obtain a visa to travel to Athens, yet the barriers were substantial, from the costs of travel to obtaining the necessary documentation. The arrival of Katerina’s letter brought forth not just optimism but also sparked reflections on our financial constraints and life under the Communist regime, which had limited travel options. A breakthrough came when my other grandmother, Nona Fozi, discovered the letter and offered her hidden gold coins to help fund the trip. With this unexpected support, plans for the journey intensified, reflecting the communal spirit of our neighbors who contributed food and other essentials for the trip. The day of our departure was a celebration, full of well-wishes and apprehension for my grandmother, who was cautious not to expose the hidden cash sewn into her skirt. When we reached the airport, mixed feelings arose as my grandmother reminisced about lost privacy and past experiences. The flight to Athens presented new experiences for me: foreign food, the air hostesses's behaviors, and comforts I had never known. In my young fascination, I documented every new sensation and experience, while my grandmother navigated the complexities of reconnecting with her past in this foreign city. Our hosts, Katerina and her husband Yiorgos, welcomed us into their affluent life in Athens, filled with opportunities that contrasted sharply with our experiences back home in Albania. My grandmother's memories flooded back as we visited her old school, her father’s grave, and her childhood home, where the passage of time revealed layers of loss intertwined with fleeting moments of joy. Despite the warmth of the reunion, there was a palpable sense of detachment on my part. I felt the weight of my grandmother’s history and the silence surrounding the unanswered questions of her choices and sacrifices. The nostalgia was tinged with sorrow as I realized that her past, including connections with family and heritage, created a chasm between us. Her struggle to reclaim a lost identity threaded through her reluctance to embrace the new while still holding on tightly to the ache of what was lost. In the end, while my grandmother sought closure on the past, I felt an urge to return to the familiar, to the safety of home—away from the weight of history and the complexities of freedom versus the necessity of her decisions. Our trip highlighted not only my grandmother's journey through grief and resilience but also foreshadowed the lingering disconnection between her older world and my emerging identity amidst a shifting landscape.

Chapter 13 | 13. Everyone Wants to Leave

On my last evening in Athens, I carefully packed a small gift for Elona—half a Milka chocolate, chewing gum shaped like a cigarette, and a loofah sponge in the shape of a strawberry. I was eager to keep my promise to bring her a present from my trip. However, upon returning to class, I learned she was ill and subsequently did not return to school for weeks. As time passed and her absence stretched into a month, I grew increasingly concerned. Eventually, I decided to visit her home. When I knocked, her father answered and dismissively referred to her as a "bad girl," slamming the door on me after I attempted to inquire about her. My heart sank when he discarded my gift into the road, emphasizing her absence. Shortly after, Elona’s name was removed from the school register. Rumors among classmates swirled regarding her fate; some speculated she had gone to live with grandparents, while others suggested she had been placed in an orphanage or even left the country entirely. Months later, I encountered Elona’s grandfather and learned the startling truth. On 6 March 1991, as Elona was on her way to school, she met with an eighteen-year-old boy named Arian. The country was in chaos, with crowds flocking to the port, hoping to flee as soldiers abandoned their posts. Arian convinced her to join him in leaving for Italy, citing that they could always return if they wanted. In a moment of impulsive courage, Elona followed Arian to a cargo ship, embarking on a perilous journey that altered the trajectory of her life. Their struggle to reach safety was harrowing, spending days as refugees under dire conditions in a makeshift camp. Eventually, they found a tiny flat in northern Italy, where they struggled to survive. Arian secured a precarious job while Elona, pretending to be his sister to navigate bureaucratic challenges, clung to the remnants of her previous life. It was unfathomable to me that someone so familiar, with whom I had shared joyful moments, could summon the bravery to abandon everything for an uncertain dream. Elona's grandfather had also attempted to leave, motivated by desperation to find her. He recounted the harrowing experience aboard the Vlora, a ship commandeered by thousands of people determined to escape Albanian turmoil. The conditions aboard were dire, with accounts of dehydration and chaos as people clamored for survival. Those sailing on the Vlora were treated as pariahs upon reaching Italy, facing rejection and confinement in a stadium where they battled for resources amidst police hostility. During discussions with Elona’s grandfather, the harsh reality of the shifting political landscape emerged. Despite having more freedom to leave the country, refugees were met with hostility abroad, treated as threats rather than victims. The once-lauded freedom of movement now seemed hollow, as barriers were erected against those striving for a better life. Emigration, which provided a temporary escape for some, paradoxically weakened the country left behind, extracting its youth and potential. As I reflected on the stark contrast between my own family’s stability and the chaos that consumed others, it became evident that the longing to leave was a driving force for many; an overwhelming desire for hope and opportunity sparked by an increasingly desperate reality. Questions about the values of freedom and belonging loomed large as the world around us transformed. The narrative of those who left mirrored the struggles of countless others, serving as a haunting reminder of the complexities of migration and the inherent contradictions in our definitions of freedom and safety. In the end, everyone seemed desperate to leave—yet the ramifications of those departures echoed long after their families were splintered, engulfing many in an uncertain future.

Chapter 14 | 14. Competitive Games

In the narrative of Chapter 14 from "Free" by Lea Ypi, the themes of redundancy, social change, and familial dynamics intertwine to reflect the upheaval of a society transitioning towards capitalism after a period of communism. The protagonist’s father, a forest engineer, faces unemployment following the closure of his office after the introduction of multi-party elections, a sign of the shifting economic landscape. This loss of job signifies more than just personal tragedy; it symbolizes the broader destruction of the natural environment as previously protected resources are now exploited for private ends. 1. The father's experience illustrates the confusion faced by individuals as they navigate this uncertain terrain of newfound ‘freedom’ and competition. While there’s an initial confidence marked by his proclamation of “I am free,” the reality soon sets in, leading to feelings of depression and disillusionment. 2. The emotional tumult within the family deepens as the mother, in a counterpoint to her husband’s descent into despair, embraces the new political landscape by joining the opposition party. Her decision triggers a conflict between her desire for agency and her husband’s need for traditional decision-making dynamics in their marriage, unsettling the established order of their relationship. 3. This tension between individualism and collectivism arises through several anecdotes, each depicting the mother’s assertiveness juxtaposed against the father’s feelings of impotence amidst their shifting roles. Her initiation of personal and political ventures fuels heated exchanges, exposing fundamental differences in their worldviews: she believes in the necessity of competition and individual accountability, while he longs for the simpler, more secure past. 4. The mother’s determination to reclaim her family’s previously confiscated properties serves as a broader metaphor for the struggle to restore historical justice in a society adapting to new economic rules. Her relentless pursuit of these assets reflects her philosophy that individual initiative can lead to prosperity, illustrating her belief in the inherent self-interest of human nature. 5. The contrast between her political activism and her husband’s increasingly fragile state underscores the generational rift, where their differing perspectives on property, responsibility, and community echo the tensions within the transitional period of their society. 6. The narrative culminates in the mother’s eloquent speeches which emphasize ideas of freedom and individual rights, resonating with a new nationalistic fervor, while the father's silence symbolizes a poignant loss not only of his job but of his identity in a rapidly changing world. In conclusion, Chapter 14 encapsulates the personal and societal discord experienced during a transformative time. Through a family's struggle with economic and political shifts, it reveals deeper questions of autonomy, responsibility, and the nature of competition within a new socio-economic framework. Ultimately, it probes the intrinsic conflict between individual desires and societal roles, reflecting the multifaceted challenges that arise in the face of historical change.

Chapter 15 | 15. I Always Carried a Knife

In late summer 1992, the anticipation of a visit from a group of Frenchwomen transformed the household into a whirlwind of preparation, reminiscent of New Year’s Eve celebrations. The family, led by my mother, undertook an exhaustive cleaning regime, reminiscent of military precision, as they prepared their home to impress the visitors. My mother, embodying the role of a commanding officer, orchestrated the cleaning efforts, ensuring every corner was spotless, while also attending to the appearance of her children. Upon the arrival of the French delegation, dressed in professional dark suits—a stark contrast to my mother’s colorful, albeit mismatched, dress—the atmosphere was charged with cultural nuances. My mother’s attire, a second-hand silk nightdress, was likely perceived by the visitors as an emblem of local custom or newfound freedom. The conversation commenced with praise for a speech my mother had given on women’s issues, but in an unexpected turn, she confessed her lack of preparation for such a topic, claiming, “I think everyone should be free, not only women.” The dialogue soon became tense when the topic of women’s harassment emerged. My mother sheepishly revealed a part of her past, admitting, “I always carried a knife,” which startled the Frenchwomen. She quickly clarified that it was just a kitchen knife, used for self-defense during her journeys to remote schools, particularly from unwanted advances while hitchhiking. Her revelation, infused with humor about a “tickle” she administered to a hand resting on her thigh, failed to dissipate the discomfort in the room. As the conversation moved forward, my mother’s frank discussion of the differences in personal defense options between Albania and the United States revealed her frustration and the limitations imposed on women’s autonomy. Although she expressed a desire for empowerment among women, her approach leaned towards individual survival rather than collective action or solidarity. The delegation's original purpose—to discuss feminist campaigns and women’s rights—found little traction as my mother redirected focus to practical realities. She adeptly navigated visa interviews, masking the true intentions of her organization’s trips abroad, which predominantly consisted of helping mothers reconnect with their emigrant children. My mother’s disdain for affirmative action was palpable as she recounted anecdotal experiences during her dealings with bureaucratic institutions. She articulated a belief that such policies were mere distractions, diverting attention from genuine issues that women faced—primarily the need for familial support. As she expressed her discontent regarding the superficiality of feminist rhetoric in the West, she underscored the realities of Albanian women's struggles that usually went unacknowledged. The narrative further delves into the contrasting dynamics of gender roles within her family and society. While my mother actively dispensed wisdom and strength, the men in her life did not share in the burdens of domesticity equally. Her expectations of women’s resilience stood in stark contrast to a societal norm where men took a backseat, perpetuating cycles of dependence and control sharpened by historical legacies. My father’s attempts at a different style of manhood, one influenced by his own family history, often fell short in practice, leaving my mother to shoulder the labor of home and family. With her fierce independence and reluctance to show vulnerability, she resisted forming alliances with other women, preferring to empower them through personal fortitude rather than collective solidarity. Her distrust of the state and reluctance to engage in institutional discussions about equality further underscored her solitary fight against societal oppression. As I reflected on my mother’s life, the implications of her resilience, combined with her evident isolation, became clear. The absence of collective action left her in a lonely battle, emblematic of countless other women whose struggles remained invisible. While she inadvertently instilled in me a sense of independence and strength, it also became apparent that her vision of empowerment was limited by her unwillingness to connect with others in solidarity, illustrating the often stark realities faced by women in a transitioning post-socialist society.

Chapter 16 | 16. It’s All Part of Civil Society

In October 1993, a seemingly ordinary afternoon took an unexpected turn for Lea Ypi when she returned home to find her grandmother waiting with a troubled expression. The conversation quickly shifted to a sensitive topic: the concept of condoms and sexual education, which sparked a series of revelations about awareness initiatives in their post-communist society. It began when Ypi was accused of discussing condoms—an incident highlighted by her grandmother’s incredulity upon learning that Ypi was merely translating a scene from a French film about AIDS for a school event organized by a new NGO called Action Plus. The NGO's mission was to educate youth about the risks of AIDS and safe practices, which was a foreign concept to her grandmother. Ypi’s grandmother, embodying the cautious wisdom of previous generations, took this opportunity to provide a crash course in sex education, emphasizing the importance of such information in preventing diseases that were not yet present in their region. She recognized that as the world transitioned and freedoms expanded, new risks—like AIDS—could follow. The realization that their society needed organizations like Action Plus led her to advocate for the necessity of civil society, a term that had recently entered their political vocabulary, symbolizing the new landscape of individual freedoms and responsibilities away from state control. This chapter reflects the heady years of post-communist activism that characterized Ypi’s teenage years, where the notion of civil society became a pivotal theme. Civic groups proliferated, allowing individuals to engage in discussions about significant issues ranging from human rights to public health, marking a shift from collective ideologies rooted in socialism to a focus on individual freedoms. One such instance was Ypi’s involvement with the Open Society Institute’s debating teams, where she engaged in discussions ranging from capital punishment to international trade organizations, highlighting the blend of social engagement with educational opportunities. As youth, they reveled not only in the discussions but also in the social benefits that came with civic involvement, such as enjoying free snacks at awareness campaigns or hanging out with peers during volunteer work with the Red Cross. While Ypi blossomed in this environment, her family navigated the complexities of a post-communist economy. Her father sought a stable professional life, facing the pressures of newfound employment and the looming challenge of learning English—a language he feared would be vital for his success in the transforming landscape. This fear highlighted the generational divide in how language skills were perceived and cultivated in their family. With her father's professional endeavors came financial strain and evolving attitudes toward money, reflecting a society grappling with capitalist principles for the first time. Ypi's grandmother began giving private lessons to help support the family, transforming their home into a makeshift classroom. The family’s careful management of finances, rooted partly in a history of debt aversion, contrasted sharply against the backdrop of emerging credit systems that many were wary of entrusting. As Ypi detailed her father's journey to conquer English, the narrative opened up the community dynamics reflecting broader societal shifts. His encounter with a group of young Americans, whom he mistakenly identified as Marines, led to English classes that brought together diverse community members, including local imams and other neighbors, facilitating rich discussions that transcended the language barrier. Through Ypi’s observations, the chapter weaves a rich tapestry of personal growth, familial responsibility, and societal change, illuminated by the seemingly simple exchanges that carry profound implications for understanding the multifaceted ideologies shaping their world. The exploration of civil society as a concept became imperative not only for survival in an evolving political landscape but also as a means of fostering individual agency amidst new social dynamics, creating a space for genuine dialogue and the synthesis of old and new traditions in a rapidly changing environment.

Chapter 17 | 17. The Crocodile

In the narrative of Chapter 17 from Lea Ypi's "Free," we are introduced to Vincent Van de Berg, colloquially known as the Crocodile. Vincent, originally from The Hague, exemplifies a modern nomad, working for the World Bank and assisting Albania with its privatization efforts. His life is marked by constant movement across various transitional societies, leading to his embarrassment over recalling the many places he has lived. He presents an image of superficial familiarity—described as bald with large glasses and sporting shirts featuring a small, embroidered crocodile—symbolizing both his wealth and distance from the local culture. Vincent's journey into the lives of the locals begins with Flamur, a street-smart boy who initially attempts to pickpocket him in a market but ends up offering his home for rent when Vincent needs a place to stay. This relationship leads to a complicated social dynamic where Flamur and his family help Vincent navigate Albanian life while observing his behavior with a mix of curiosity and judgement. The community's perception of Vincent shifts notably during a welcome dinner organized by the neighbors. Although the occasion begins with joyous celebration—filled with abundant food, music, and dancing—the evening culminates in Vincent's unexpected outburst. Despite his polite demeanor, he reveals a profound stress when pressed into dancing, asserting, “I am free!” His declaration resonates as a troubling reminder of the social barriers that isolate him from those around him, transforming his image from the wealthy foreigner to ‘the poor man’ in their eyes. The chapter highlights the contrasting perspectives between Vincent and the locals. While he navigates life through the lens of his global experiences, sharing anecdotes that often render their unique cultural practices as commonplace, the community grapples with feelings of inadequacy and alienation in the face of his cosmopolitan worldview. Vincent’s experiences seem to diminish the distinctiveness of their lives, revealing a universal thread that complicates their self-identity. As Vincent explores the countryside on weekends, he adopts a semblance of typical tourist behavior, yet remains fundamentally ensnared in his own alienation from the community. His interactions—marked by politeness yet imbued with his detached worldview—leave the locals puzzled. The chapter contrasts Vincent’s view of the world as a series of transitions against the villagers’ fixation on national and cultural identity, unveiling the nuances of shared humanity amidst isolation and misunderstanding. Ultimately, this chapter illustrates the complexities of integration and belonging, reflecting on how external perceptions and cultural narratives shape identity. As Vincent maneuvers through his role as an expatriate, the community observes, interprets, and ultimately defines him through their collective lens—one that simultaneously reveals their own insecurities and entrenched values. The collision of Vincent's global perspective with local consciousness underscores the intricate dance between understanding and alienation, forging a narrative rich with cultural commentary and personal struggle.

Chapter 18 | 18. Structural Reforms

In a reflective moment on a blustery November morning, the narrative unfolds through a conversation between Lea Ypi and her father. He poses a thought-provoking question about the most challenging experience he has faced. Humor tinged with darkness characterizes their exchange, as they reminisce on the absurdities and hardships of life during the final throes of socialism. The father, having been promoted to a high-ranking position at the port, now confronts a bitter reality. As he contemplates the repercussions of his job, he gives voice to the emotional weight of structural reforms that dictate the layoffs of workers, particularly from marginalized communities such as the Roma. 1. The Shift in Familial Dynamics: The father, having climbed the corporate ladder, is torn between the responsibilities of his position and the human cost of structural reforms. His new daily routine of dealing with foreign experts like Van de Berg, charged with the task of modernizing the port, leaves him with little room for personal comfort. Despite his initial excitement over climbing the ranks, his conscience wrestles with the impact of decisions that will result in job losses and the shattering of lives that depend on him. 2. The Human Cost of Economic Policy: As news of impending layoffs spreads, a steady procession of workers begins to gather outside their home, pleading with him to reconsider the decisions he feels are out of his hands. Their desperate appeals—filled with promises of personal sacrifice and declarations of loyalty—serve to heighten his internal conflict. He feels the immense burden of their hopes resting on his shoulders, yet he grapples with the idea that he is merely a cog in a larger machine, driven by economic policies dictated from above. 3. The Dissonance of Duty and Morality: The father’s struggle manifests in visceral ways; he is aware of the disparity between the people he encounters and the bureaucratic processes he must implement. The juxtaposition of the emotional pleas from workers, including Ziku, a familiar face from his past, against the backdrop of economic rationale is jarring. Though he attempts to rationalize the need for reform—framing it as a necessary evolution towards a market economy—his heart rebels against the notion that people can be replaced like machinery. 4. The Weight of Memory and Accountability: As he contemplates the gravity of his decisions, he acknowledges the danger of reducing people to mere statistics, an outcome he cannot reconcile with his values. His fear of forgetting those who depend on him—turning them into faceless numbers—fuels his anxiety. The memories of collective survival through past hardships weigh heavily on him, as he reflects on the moral implications of succumbing to the very institutional frameworks that once oppressed him. 5. The Complexity of Freedom and Change: The narrative reveals a generational tension, as the father’s experiences with oppression shape his outlook on freedom and responsibility. He grapples with the paradox of his newfound authority. Though he yearns for radical change and dreams of collective goodwill, he finds himself entangled in a system he mistrusts. No longer the victim, he feels the insidious pull to negotiate his ideals against the confrontational demands of reality, often questioning whether those operating from good faith can inadvertently cause harm. Through this deeply introspective chapter, Ypi illustrates the profound complexities and contradictions inherent in the pursuit of economic reform, the burden of leadership, and the perennial human struggle for dignity and compassion amidst transition. The father’s moral turmoil encapsulates a broader commentary on the societal shifts taking place within the context of a changing political landscape, ultimately highlighting the enduring impact of individual choices against the imperatives of history and systemic change.

Chapter 19 | 19. Don’t Cry

In the mid-nineties, the author reflects on the emotional turmoil of her teenage years, characterized by a profound sense of confinement and denial of her feelings by her family. Her upbringing emphasized that only those in dire circumstances were justified in feeling miserable, trivializing her struggles and urging her to feel grateful for newfound freedoms that her parents had once longed for. This environment stifled her sense of autonomy, particularly suffocating during long, dark winters that limited her social interactions. With the outside world posing various dangers, such as accidents and violence, her parents enforced strict rules that kept her indoors. During these isolated afternoons, she found solace in small rituals, like chewing sunflower seeds and losing herself in books by candlelight due to frequent power outages. Her grandmother, concerned about her well-being, routinely barged into her room, offering food in a bid to shield her from a newly identified issue, anorexia, while unintentionally highlighting the harsh realities faced by their family. As the day-to-day landscape of her life transformed, the new freedoms coexisted oddly with emerging societal issues. Out-of-work neighbors turned to crime, and clubs opened under the shadows of illicit trades. In this chaotic environment, encounters at daytime gatherings introduced her to a confusing social landscape where gender roles blurred, and the innocence of childhood began to collide with societal expectations. She often yearned for her friend Elona, who had seemingly escaped to a world of freedom, raising questions about the paths they could have taken. Her nostalgia laid bare the stark differences between their lives as she mulled over shared memories and the realities that had overtaken them. The arrival of summer brought its own set of challenges, marked by forbidden crushes and a search for identity amid confusing emotions and the unexplainable allure of attraction. In an effort to cope with her feelings and gain perspective, she volunteered at a local orphanage. This endeavor not only exposed her to the distressing conditions faced by abandoned children but also stripped her of her escapist tendencies. One little boy, Ilir, became particularly attached to her, mistaking her for his estranged mother. Their bond reflected a profound longing in both, evolving into a bittersweet relationship that was ultimately unsustainable. As the project concluded and her connections faded, the author was left pondering the fates of Ilir and Elona, encapsulating a cycle of longing, loss, and the bittersweet realities of growing up in a tumultuous time. Heavy with memories and the starkness of her transition from childhood to adolescence, she returned to the familiar confines of her bedroom, where her grandmother continued to insist on their luck in the face of adversity. The chapter closes with a poignant reflection on the intertwining lives of love, loneliness, and the painful journey toward understanding oneself in a world marked by upheaval.

Chapter 20 | 20. Like the Rest of Europe