Last updated on 2025/05/04

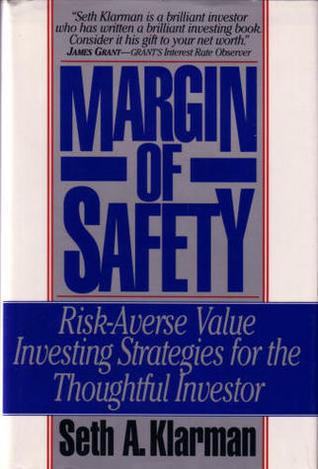

Margin Of Safety Summary

Seth A. Klarman

Investing with a focus on risk management and value.

Last updated on 2025/05/04

Margin Of Safety Summary

Seth A. Klarman

Investing with a focus on risk management and value.

Description

How many pages in Margin Of Safety?

248 pages

What is the release date for Margin Of Safety?

In "Margin of Safety," renowned investor Seth A. Klarman distills decades of wisdom on value investing, emphasizing the critical importance of a margin of safety when making investment decisions. With market volatility and uncertainty ever-present, Klarman advocates for a disciplined approach that prioritizes capital preservation over reckless speculation, urging readers to look beyond conventional metrics and identify undervalued securities. Through insightful analysis and real-world examples, this essential guide not only equips investors with the tools needed to navigate financial markets but also instills a philosophical framework for sustainable wealth creation. Whether you are a seasoned investor or just beginning your financial journey, Klarman’s principles challenge you to think differently about risk, opportunity, and the true nature of value.

Author Seth A. Klarman

Seth A. Klarman is a prominent American investor, philanthropist, and author, widely regarded as one of the most successful value investors of his generation. Born in 1957, Klarman founded the Baupost Group, a Boston-based investment firm, in 1982, where he has applied his disciplined, research-driven approach to investing, amassing significant wealth and earning a reputation for his insightful market analyses. He is a strong advocate of the Benjamin Graham and David Dodd principles of value investing, underscoring the importance of risk management and intrinsic value in investment decisions. Klarman's book "Margin of Safety: Risk-Averse Value Investing Strategies for the Thoughtful Investor" is highly esteemed in investment circles for its deep insights and practical guidance, cementing his influence on both professional and individual investors.

Margin Of Safety Summary |Free PDF Download

Margin Of Safety

Chapter 1 | Speculators and Unsuccessful Investors

In Chapter 1 of "Margin of Safety" by Seth A. Klarman, the author emphasizes the critical distinction between investing and speculation as a foundational step toward achieving investment success. Reflecting on Mark Twain's jest, Klarman notes that both the ability to afford speculation and the timing of such activity significantly influence outcomes. 1. Investment as Ownership: Investors perceive stocks as partial ownership of businesses and bonds as loans to these enterprises. Their decisions to buy or sell securities are based on perceived value versus current prices. Investors transact when they believe their insights into a company’s value exceed the collective understanding of the market. Thus, they aim to purchase securities offering favorable returns relative to the risks involved. 2. Expectations of Profit: Investors anticipate profits through mechanisms such as generated free cash flow, increases in valuation multiples, or narrowing discrepancies between market price and intrinsic value. This is long-term focused and grounded in the fundamentals of the underlying business. 3. Speculation Defined: In stark contrast, speculators operate without regard for the underlying business fundamentals, making decisions based on anticipated price movements rather than intrinsic values. They frequently engage in predicting market behaviors, indulging in technical analysis that relies on historical price patterns rather than understanding the business itself. Notably, speculators often embrace the unpredictable nature of the market, viewing securities merely as tradeable items rather than valuable investments. 4. The "Greater Fool" Theory: Klarman highlights how many market participants are unknowingly caught in a "greater-fool game," continuously buying overpriced securities with the hope of offloading them to an unsuspecting buyer at an even higher price. This mindset exemplifies a fundamental misunderstanding of the market, equating trading with investing. 5. Market Illusions and Bubbles: The text discusses situations where speculative bubbles form, such as the high market value of disk-drive manufacturers in the 1980s, pointing to a failure of market fundamentals to justify valuations. This bubble ultimately burst, leading to significant financial losses for investors. 6. Speculative Conduct in Various Markets: Klarman provides real-world examples like the Spain Fund and U.S. Treasury bonds, where securities were traded without considering their fundamental value. By prioritizing liquidity, these assets often transformed into "trading sardines," susceptible to volatile market conditions. 7. Investing vs. Speculating Assets: While both investments and speculations exist in the market, the key differentiation hinges on cash flow. Investments yield returns that benefit their owners, while speculations' returns are dependent solely on resale value, often leading to losses. High levels of speculation can obscure true asset valuations, resulting in market distortions. 8. Investor Emotionality and Greed: Klarman observes that successful investors maintain a rational and unemotional approach, making decisions grounded in data rather than emotions of fear and greed. Emotional investors often react irrationally during market fluctuations, leading to poor decision-making. 9. The Irrationality of Mr. Market: Klarman introduces the concept of "Mr. Market," an allegorical figure representing the erratic behavior of financial markets. Wise investors leverage the irrational pricing set by Mr. Market to buy undervalued securities or sell overvalued ones, rather than react on impulse. 10. Irrelevance of Price Movements: Investors need to distinguish between price fluctuations and the actual business value. A rising share price might not indicate an increase in company value, and vice versa. This keen observation allows investors to make informed decisions based on intrinsic rather than market-derived values. 11. The Quest for Investment Formulas: Klarman critiques the frequent search for simplistic investment methodologies, pointing out that financial markets are too complex for easy formulas. Historical performance does not guarantee future returns, and investors should pivot from formulaic approaches toward rigorous analysis of potential investments. In conclusion, Klarman emphasizes the pervasive challenges of distinguishing investment from speculation in financial markets and articulates the various psychological and market dynamics that can mislead investors. Investors must cultivate a disciplined mindset, informed by fundamental analysis and an awareness of the temptations and traps of speculation, to optimize their chances of long-term success.

Key Point: Investment as Ownership

Critical Interpretation: Imagine shifting your perspective from merely seeking profit to truly owning a piece of a business; this profound realization can inspire you to invest your time, resources, and passion in meaningful endeavors. Just as a true investor looks at stocks as ownership stakes in companies, you can approach your own life decisions similarly, fostering a deeper commitment to the projects and relationships you engage in. By focusing on the intrinsic value of your choices—whether they relate to your career, personal development, or your relationships—you cultivate not just financial wealth but also personal fulfillment. Embracing the mindset of investment encourages you to assess the long-term potential of your engagements, nurturing them through diligent effort and wise decision-making, instead of succumbing to fleeting speculations that offer quick but empty rewards.

Chapter 2 | The Nature of Wall Street Works Against Investors

In the complex realm of marketable securities, investors find themselves dependent on Wall Street, yet paradoxically, often underserved by it. Recognizing that the imperatives of Wall Street do not always align with investors' best interests is crucial. The primary functions of Wall Street encompass trading, investment banking, and merchant banking. In trading, firms act as intermediaries, collecting commissions that are uninfluenced by the outcomes for investors. As investment bankers, they facilitate major transactions and manage the issuance of new securities, often prioritizing their compensation over the welfare of their clients. Merchant banking, being more direct and involving the use of firms' own capital, intensifies these conflicts, blurring lines between being an advisor and a competitor. 1. Conflict of Interest and Compensation Structures: The core conflict resides in the compensation model prevalent on Wall Street, which is fundamentally based on up-front fees rather than ongoing performance metrics. Brokers and bankers earn their fees regardless of how well their clients fare post-transaction. This model incentivizes behavior that may lead to excessive trading and prioritization of high-commission products, often to the detriment of the investors’ interests. 2. Bias Toward Underwriting Over Secondary Transactions: Wall Street shows a pronounced preference for underwriting new securities versus facilitating secondary-market transactions. The commissions from new issues can far exceed those from trades between existing securities. Consequently, brokers may push newly underwritten securities, often neglecting to adequately assess their true value or potential risks before recommending them to clients. 3. Investor Awareness of Market Dynamics: Investors must remain vigilant and informed about the motivations behind the recommendations made by their brokers. The interplay between imminent commissions and transaction outcomes can lead to conflicts that ultimately leave investors at a disadvantage—this is particularly true in the context of initial public offerings (IPOs) where the potential for overpricing and high risks must be scrutinized thoroughly. 4. Short-Term Focus: The compensation structure fosters a short-term mindset among Wall Street professionals, leading to a tendency to focus on immediate transactions rather than sustainable long-term investment strategies. This is compounded by the belief that client relationships are transient, facilitating a cycle of high turnover and promoting a culture of maximizing immediate gains. 5. Wall Street’s Bullish Bias: Investors need to recognize the inherent bullish bias that pervades Wall Street. The prevailing inclination towards optimism—often manifested in research reports and analyst recommendations—can obscure the risks involved with investments. Acknowledgment of this bias is essential for investors to maintain a balanced view of potential upside versus the downside risk. 6. Financial Innovations: Wall Street constantly seeks to innovate, offering new securities that potentially address market needs but often serve the firm’s interest in generating fees. The emergence of complex financial instruments is not always beneficial for investors, as the focus can pivot from sustainable value generation to crafting lucrative products for the firm. 7. Investment Fads: The market is subject to cycles of enthusiasm for various investment themes. Historical trends reveal that securities related to popular industries can become inflated in value, often leading to sharp corrections when investor zeal wanes. An understanding of this ebb and flow is vital for investors to navigate the speculative waves and to discern between genuine value and fleeting trends. In conclusion, while engaging with Wall Street is inevitable for investors, a critical awareness of its motivations, practices, and inherent biases is essential for navigating this landscape. By understanding these dynamics, investors may better equip themselves to make informed decisions and protect their interests in a climate that often prioritizes Wall Street's self-serving strategies over genuine investment stewardship.

Chapter 3 | The Institutional Performance Derby: The Client Is the Loser

The evolution of institutional investing has significantly influenced the financial landscape over the last thirty years, particularly as retirement and endowment funds sought secure investment avenues. This chapter discusses the ramifications of this shift, particularly how it has inadvertently hampered performance outcomes for the very funds it aimed to enhance. 1. Rise of Institutional Investors: The transformation of the investment world began with the transition from individual investors to institutional ones, driven by the increasing capital in pension and endowment funds after World War II. While the investment menu expanded, the essence of investing shifted towards portfolios managed by professionals. 2. Short-Term Focus: Institutional investors are predominantly guided by a need for relative-performance—a fixation on outperforming their peers over short time frames. This approach detracts from the long-term objectives that would benefit retirement funds, leading to suboptimal investment choices driven by market trends rather than fundamental analysis. 3. Impact of Bureaucracy and Marketing: The structural complexities within institutional investing, where marketing often outweighs investment insights, lead to diminished performance. Money managers invest considerable time in nurturing client relationships rather than focusing on effective investment decisions. This dilutes the energy that could otherwise be directed towards enhancing returns for clients. 4. Groupthink Dynamics: The culture of compliance and conformity within investment firms fosters a reluctance to take independent or unconventional investment decisions. As fear of underperformance overshadows the potential for superior outcomes, mediocrity becomes the norm, perpetuated by the tendency to follow what is deemed safe or conventional. 5. The Short-Term Derby: Money managers have inadvertently engaged in a “short-term derby,” driven by constant performance assessments and comparison with peers. This short-sighted behavior prevents them from identifying long-term investment opportunities and instead leads to a vicious cycle of subpar returns. 6. Misaligned Incentives: Institutional managers often have compensation structures that incentivize asset growth rather than performance excellence. This conflict of interest can result in decisions that prioritize fee generation rather than sound investment strategy, leading to deteriorating outcomes for clients. 7. Self-Imposed Constraints: Institutional managers impose restrictions on their investment practices—such as mandates to remain fully invested—that counteract the principles of sound investment. These constraints can lead to the acquisition of less favorable investments simply to meet arbitrary rules, sacrificing potential returns. 8. Failure of Fundamental Analysis: Increasingly, some institutional investors are opting to ignore fundamental analysis altogether. Instead, they endorse strategies such as indexing or tactical asset allocation, which prioritize market movements over the underlying financial health of the companies in which they invest. This shift is risky, as it may exacerbate inefficiencies in market pricing. 9. Indexing Dangers: The rise of indexing reflects a herd mentality among investors who seek to eliminate risk by passively tracking market indices. While this simplifies investment management, it leads to the neglect of potential undervalued opportunities and is ultimately counterproductive. 10. Market Vulnerabilities: The sheer volume of institutional trading exacerbates volatility. When indexes are adjusted due to changes in component companies, the rush to buy or sell can disproportionately inflate or deflate stock prices, disconnected from their intrinsic value. 11. Conclusion: For investors, understanding institutional behavior is essential. The dominance of institutions in trading means that individual investors can benefit from recognizing where inefficiencies lie and capitalizing on neglected prospects. Insight into the institutional psyche, akin to having a map in unfamiliar territory, can assist individual investors in navigating the complexities of the market effectively. Through the lens of this chapter, it is evident that while institutional investing has redefined the landscape, the priorities and operational strictures of these investors can cloud the path to long-term, stable financial growth.

Chapter 4 | Delusions of Value: The Myths and Misconceptions of Junk Bonds in the 1980s

The chapter delves into the emergence and subsequent turmoil of the junk-bond market that flourished in the 1980s. It outlines several key principles regarding the factors contributing to its rise, the flawed logic behind its perceived safety, and the eventual fallout experienced by investors and corporations alike. 1. The success of the junk-bond market was heavily influenced by a confluence of greed and ignorance among different market participants. Individual investors were lured by the promise of high returns, while institutional investors, driven by short-term gains, overlooked the inherent risks. Wall Street’s self-serving behaviors further facilitated the proliferation of this market, allowing it to expand to a staggering $200 billion without adhering to conventional investment wisdom or proven economic fundamentals. 2. Despite early success, which created unrealistic expectations, the junk-bond market harbored fundamental flaws. Originally seen as irresistible investments due to their offered yields, by 1990 the junk-bond market faced significant troubles as defaults soared and prices plunged. The instruments lacked a margin of safety and were mischaracterized as low-risk opportunities when, in reality, they exhibited characteristics that amplified risk. 3. The cornerstone of the junk-bond phenomenon stemmed from Michael Milken, who demonstrated that portfolios of low-rated bonds could yield better returns than higher-rated ones. However, this premise exaggerated risk tolerances and disregarded the fundamental differences between newly issued junk bonds and traditional fallen angels, misleading investors into believing in sustainable security. 4. Compounding the issue were faulty default-rate calculations. Proponents of junk bonds touted a low default rate to justify investments, yet these calculations failed to factor in significant realities. They ignored the time lag associated with defaults and the distinction between defaults and investor losses; fallen angels that did default had less far to fall than newly issued junk bonds trading at par. 5. The growth of the junk-bond market was characterized by moral hazard as investors, blinded by bullish sentiment, lost sight of traditional valuation metrics. The market believed junk bonds to be a panacea for economic malaise, with some advocating that they could rejuvenate struggling companies. However, many were unaware that the majority of junk-bond issuers were burdened by excessive leverage, leaving them vulnerable to economic downturns. 6. Notably, the participation of institutions like mutual funds, thrifts, and insurance companies exacerbated the crisis. Mutual fund managers, driven by competitive pressures, were compelled to chase higher yields, leading to the acquisition of increasingly lower-quality junk bonds. This behavior encapsulated the "Gresham’s Law of Junk Bonds," wherein bad investments drove out the good. 7. A significant part of the problem was the shift in accepted methodologies for evaluating a company’s financial health. Investors began using EBITDA as a proxy for cash flow, which obscured the true costs of capital expenditures and financial responsibilities, resulting in rampant overvaluations of firms that failed to account for their operational realities. 8. The chapter emphasizes that the legacy of the junk-bond crisis lingers in the fabric of financial markets. The misguided faith in the risk-return relationship of junk bonds led to inflated valuations across sectors, distorting investor behavior. 9. Ultimately, the junk-bond market serves as a cautionary tale; an exploration of how collective misjudgments in investor logic can culminate in catastrophic financial outcomes. This history raises an important lesson for contemporary investors: recognizing and avoiding emerging financial fads that inflate beyond their supportive fundamentals is crucial to achieving long-term success. In conclusion, the narrative of the junk-bond boom illustrates the dire consequences of speculative investing, underscoring the necessity of maintaining rigorous analytical standards and discernment amidst market exuberance. Understanding this historical financial misstep can better prepare investors to navigate future market anomalies and prioritize sustainable investment practices.

Key Point: Recognizing the importance of a margin of safety in investments.

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing on the edge of a great precipice, tempted to leap into the enticing allure of high returns, the rush of adrenaline masked by the smooth talk of financial advisors. This chapter reveals a significant truth: just as investors fell prey to the seductive promise of junk bonds without acknowledging the underlying risks, we often chase after immediate gratification in our lives, neglecting the potential fallout that might ensue. Embracing the principle of maintaining a margin of safety doesn’t just apply to financial investments; it translates seamlessly into our everyday choices. It encourages you to evaluate your decisions critically, ensuring that you have a cushion of security in your commitments and aspirations. By fostering this mindset, you learn to navigate the complexities of both the market and your personal journey, prioritizing sustainable growth over fleeting gains. This approach empowers you to withstand life's challenges, fostering resilience and strategic foresight, ensuring that when you finally take a leap, it’s grounded in careful consideration and robust preparation.

Chapter 5 | Defining Your Investment Goals

Warren Buffett famously articulates that the first rule of investing is to "Don't lose money," followed by a reminder to "Never forget the first rule." This philosophy resonates deeply with the idea that loss avoidance should serve as the primary focus for every investor. The aim is not to eliminate all investment risks, but rather to ensure that a portfolio is not significantly jeopardized over time. Despite inherent speculative tendencies that lead many investors to chase after high returns, the most reliable path to long-term success lies in prioritizing the avoidance of loss. Investors often misunderstand the concept of risk, believing the real danger lies in not owning stocks rather than in the ownership itself. While it is true that equities tend to outperform bonds and cash over extended periods, this historical trend does not provide a clear indication of future performance or the potential risks involved. The inherent risk in equities, exacerbated by overpaying, calls for a careful evaluation of price at the time of investment. Many believe that high returns can only be achieved through high risk, leading them to ignore risk avoidance as a strategy for investment success. However, a deeper understanding shows that risk aversion should be the foundation of any investment strategy, as large losses can have a devastating compounding effect on an investor’s wealth over time. The principle of compounding underscores the importance of consistency in returns, revealing that even slight differences in performance can have significant long-term consequences. 1. The importance of compounding: Moderate returns compounded over years result in significant wealth accumulation. Conversely, experiencing a large loss disrupts this compounding effect, potentially erasing years of investment success. 2. The unpredictability of the future: The market's behavior is uncertain, including economic growth, inflation rates, and interest fluctuations. Investors must be prepared for unexpected downturns and should manage their portfolios to withstand adverse conditions, recognizing that some near-term gains may need to be sacrificed for long-term resilience. 3. Misguided investment goals: Investors often set specific return objectives, mistakenly believing that determination will yield results. Unlike labor-based earnings, investment returns cannot be coerced; they require a disciplined approach and careful risk management over time. 4. The risk of targeting returns: Aiming for predetermined gains can lead to accepting excessive risk. Without careful consideration of downside risk, investors may find themselves entrenched in investments that actually jeopardize their capital for the hope of achieving high returns. 5. Prioritizing risk over returns: It’s essential for investors to assess potential risks rather than fixating on target rates of return. With Treasury bills viewed as essentially risk-free, any investment carrying risk must justify its risk premium with significantly higher expected returns. Ultimately, the strategy of value investing, as explored in forthcoming chapters, emphasizes loss avoidance and careful risk assessment as key elements of a successful investment philosophy. By concentrating on these principles, investors can navigate the unpredictable nature of markets while remaining focused on sustaining growth and protecting their capital.

Chapter 6 | Value Investing: The Importance of a Margin of Safety

Value investing is defined as the practice of purchasing securities at a market price that is significantly lower than their intrinsic value and holding them until their true worth is recognized. The essence of this discipline lies in the concept of finding bargains, which is often articulated in investment terms as acquiring a dollar for fifty cents. 1. Value investors engage in a rigorous assessment of a security's underlying value and exercise the discipline to invest only when they perceive a sufficient margin of safety—a disparity between market price and intrinsic value. Given the variable nature of available bargains, the value investor may sift through numerous potential investments without identifying any worthy opportunities. Patience and diligence are critical, as genuine value can often be obscured. 2. It is important for value investors to exhibit a risk-averse mentality by awaiting the right opportunities, much like a baseball player who only swings at the best pitches. They tend to avoid overvalued industries or those with complex risks, such as technology or commercial banking, unlike many institutional investors who feel pressured to remain fully invested regardless of relative value. 3. The valuation of businesses is inherently complex and uncertain, which makes it vital for investors to be conservative in their assessments. Numerous factors like changing credit conditions, inflation, and market sentiment can significantly impact business valuations, resulting in market inefficiencies. Therefore, value investors must carefully differentiate between fundamentally sound investments and those whose values are illusory. 4. Benjamin Graham emphasized the need for a margin of safety, arguing that purchasing securities below their intrinsic value is crucial to minimizing potential losses. This concept implies that investors must be aware of their own tolerance for risk and adjust their investment strategies accordingly. Those who neglect to seek a margin of safety expose themselves to greater risks. 5. The margin of safety allows for human error and unforeseen market fluctuations and is determined by the price paid for an asset relative to its value. The greater the discount, the larger the margin, enhancing the investor's ability to weather potential downturns. 6. In turbulent markets, the merit of value investing becomes evident. Investments that may not shine during strong markets often outperform during downturns, as their prices may not be buoyed by excessive expectations. Consequently, value investors can capitalize on opportunities that arise from depressed valuations in broader market corrections. 7. Value investing thrives upon the mispricing of securities, suggesting that the prevailing efficient-market hypothesis does not accurately reflect the reality of how prices are established. Market inefficiencies often arise from emotional decisions and behavioral biases among investors, which can lead to significant deviations from true valuations. 8. Lastly, investors must discern true value from pretenders. The label of “value investing” has been misapplied over time, resulting in strategies that diverge from the foundational principles established by Graham. True value investors adhere to prudence and seek genuine bargains, whereas those who exploit the term for trend-chasing strategies may find temporary success, which often leads to losses when the market normalizes. In essence, while simplicity underlies the value investment philosophy, the path to success is fraught with challenges that require disciplined analysis, patience, and sound judgment to achieve and maintain a genuine margin of safety.

Key Point: The importance of patience and diligence in seeking true value.

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing at a vast market, surrounded by glittering offers and fleeting trends that all seem enticing. In that moment, take a breath and embrace the wisdom of patience and diligence as guiding lights in your life. Much like a seasoned value investor who meticulously assesses intrinsic worth before making a move, you can apply this principle to your personal and professional endeavors. Instead of rushing into decisions driven by excitement or peer pressure, allow yourself the grace to sift through options, waiting for the opportunities that genuinely resonate with your values and aspirations. By cultivating a mindset of discernment, you not only protect your resources but also pave the way for profound growth and fulfillment in a world that often prioritizes quick gains over long-term stability.

Chapter 7 | At the Root of a Value-Investment Philosophy

In Chapter 7 of "Margin of Safety," Seth A. Klarman articulates the foundational principles that define a value-investment philosophy. At its core, value investing is characterized by three fundamental components. First, it follows a bottom-up strategy focused on identifying specific undervalued opportunities, rather than relying on macroeconomic trends. Second, it prioritizes absolute performance over relative performance; the aim is to achieve genuine returns regardless of market comparisons. Lastly, it adopts a risk-averse approach, maintaining a keen awareness of possible failures while pursuing returns. 1. The Merits of Bottom-Up Investing: Klarman contrasts the bottom-up approach with the prevalent top-down methodology used by many institutional investors. The top-down strategy involves making broad economic predictions and then narrowing down to specific investments based on those forecasts, a process fraught with challenges, including the necessity for precise predictions about macroeconomic conditions and sector impacts. The inherent complexity and speed required make this a risky game, potentially more about speculation than genuine investment. In contrast, value investing simplifies this process, emphasizing fundamental analysis of individual securities and their intrinsic values to identify investment opportunities. This strategy promotes patient and disciplined investment, allowing for cash reserves to be held until attractive opportunities arise without attempting to time the market. 2. Adopt an Absolute-Performance Orientation: Klarman critiques the relative performance mindset of many investors who focus on outperforming others or benchmarks, often leading them to chase trends at the expense of genuine value. Value investors, however, are committed to pursuing absolute performance, driven by the goal of achieving specific investment returns rather than competing against market indices. This perspective fosters a longer-term investment horizon, allowing for the possibility of enduring temporary underperformance in pursuit of undervalued assets with solid long-term potential. Holding cash when markets are overpriced is a strategic decision for value investors, contrasting with the habits of relative performers who often feel compelled to remain fully invested. 3. Risk and Return: Klarman highlights the typical investor's concerning preoccupation with potential gains over losses. A significant misconception lies in the belief that risk and return always correlate positively; this notion can mislead investors regarding their risk assessments and decisions. A focus on the risks associated with income loss, fluctuating valuations, and market inefficiencies is crucial, as these risks are independent of volatility metrics like beta. The nature and price of an investment significantly influence risk, and the emphasis should be placed on the inherent risk of destruction tied to specific business attributes and market valuations rather than purely on historical price movements. 4. The Nature of Risk: Investment risks are multifaceted, encompassing both inherent risks based on the nature of the investment and those influenced by market prices. Risk cannot be quantified accurately by a single number or statistic, as its perception varies widely among investors. Klarman urges investors to adopt strategies that mitigate risk through diversification, hedging, and most importantly, investing with a margin of safety, thus ensuring a buffer against unexpected downturns in valuation. 5. The Relevance of Temporary Price Fluctuations: Klarman addresses the dichotomy between temporary market volatility and the underlying value of investments. While short-term price fluctuations can impact investor psychology and decision-making, discerning between temporary volatility and lasting depreciation is crucial. Long-term value investors are more concerned with acquiring undervalued assets, as they recognize that market prices will eventually reflect the fundamental worth of their investments. He emphasizes holding cash to weather market declines, allowing investors the freedom to seize new opportunities without being pressured into unfavorable market sales. In conclusion, Klarman's exposition on value investing encapsulates the principles that guide investors aiming to minimize loss. Through a methodical, bottom-up approach focusing on absolute performance and prudent risk management, investors can navigate market complexities and align their strategies with long-term financial success. Ultimately, the preservation of capital remains paramount, guiding decisions across varying market conditions and investment opportunities.

Chapter 8 | The Art of Business Valuation

In the intricate world of investing, the challenge of accurately valuing businesses remains a formidable task. Many investors attempt to assign precise values to their investments, yet this pursuit of precision is often misguided when it comes to business valuation. The financial metrics at our disposal, such as book value, earnings, and cash flow, are merely estimates that reflect accountants' interpretations rather than precise economic realities. More importantly, business value is not a static figure; it fluctuates due to an array of macroeconomic, microeconomic, and market factors. Thus, a critical aspect of successful investing is the ongoing reassessment of these estimated values to adapt to changing circumstances. Evaluating the value of businesses cannot be achieved with the same certainty as valuing standard debt instruments like bonds, which offer contractual cash flows. The intrinsic value of a business is best understood within a range rather than as a fixed number. Benjamin Graham, a pioneer of value investing, emphasized that investors should focus on establishing a range of intrinsic value instead of aiming for an exact figure. This principle acknowledges the inherent uncertainty and difficulty in valuing businesses, particularly in a market saturated with varied expert opinions and estimations. When investors approach business valuation, they must employ different methodologies, as no single approach is universally applicable or definitively precise. Among the methods available, three are particularly crucial: 1. Net Present Value (NPV) Analysis: NPV calculates the discounted value of future cash flows a business is expected to generate. While it can yield accurate estimates under stable conditions, predicting future cash flows is fraught with uncertainty, often driven by unpredictable market variables and operational risks. 2. Liquidation Value Analysis: This method focuses on the potential value of a company’s tangible assets if it were to liquidate. It serves as a conservative assessment, useful for investments trading below their liquidation value, as it suggests a safety net for investors should the business fail. 3. Private-Market Value Analysis: This valuation method corresponds to the price that informed buyers would pay for a business, based on historical transactions. However, investors should apply caution here as market conditions and buyer motivations vary, potentially skewing perceived value. While investors can utilize present value and liquidation analyses, the various assumptions underlying cash flow parameters, discount rates, and legal liabilities introduce a layer of complexity that requires prudent management. The choice of discount rate further complicates the analysis; it reflects an investor's perception of risk and market conditions. Many investors oversimplify this step, often defaulting to arbitrary figures without consideration for the specific investment context. Growth-oriented strategies, which often hinge on optimistic earnings forecasts, come with their own set of challenges. Investors may become unduly confident in their projections, which, if incorrect, can lead to significant losses. Moreover, growth forecasts can vary widely based on numerous factors, including market share dynamics and pricing strategies, making precise predictions exceedingly difficult. In valuing potential investments, it is paramount for investors to maintain a conservative approach and to base their decisions on analysis rather than speculation. Successful value investing requires discipline in balancing optimistic market outlooks with cautious projections, alongside a focus on buying securities at a discount to their intrinsic values. In considering Esco Electronics as a specific case study, we can observe these principles in action. Following its spin-off, Esco's shares were undervalued, reflecting market mispricing rather than its intrinsic realities. A thorough examination of its future cash flows and potential growth led to a range of estimated values that suggested a significant margin of safety for investors. As this analysis underscores, metrics like earnings, book value, and dividend yield play a role in evaluating investments but must be scrutinized for their limitations. They cannot be treated as absolute indicators of value; instead, they should be considered as components of a comprehensive valuation framework that accounts for the complexities of real-world business dynamics. Ultimately, the task of valuing businesses is challenging and rife with uncertainty. Investors must remain patient, diligent, and selective. By focusing on businesses they understand and employing a mix of valuation methods, they can navigate the market's complexities and position themselves for long-term success.

Key Point: Embrace Uncertainty and Adaptability in Life Decisions

Critical Interpretation: Just as valuing a business requires acknowledging the inherent uncertainty and fluctuations in market conditions, so too does navigating the unpredictable landscape of life. Instead of seeking a fixed, accurate path or outcome, allow yourself the flexibility to reassess your goals and values as circumstances evolve. Embracing this mindset encourages you to cultivate resilience and adaptability, equipping you to handle challenges with grace. By recognizing that life’s true value lies not in precise calculations but in a range of possibilities, you can make decisions that are informed yet open to change, ultimately leading you to deeper fulfillment and success.

Chapter 9 | Investment Research: The Challenge of Finding Attractive Investments

In the journey toward investment success, one of the foundational steps lies in identifying where to locate potential opportunities. Investors, by nature, are tasked with processing information; however, much of their time is often consumed by analyzing a multitude of fairly priced securities that lack unique potential. Exceptional investment ideas are not commonplace; they require diligent search and critical observation, rather than simple reliance on the recommendations from well-known Wall Street analysts or algorithms. It’s essential to categorize value investing into three primary niches: 1. Securities Selling Below Liquidation Value: Investors can employ computer screening to identify stocks trading at a discount; however, verifying the accuracy of these data is crucial since outdated databases can lead to misleading conclusions. 2. Rate-of-Return Situations: This category includes risk arbitrage opportunities, where expected rates of return can be assessed based on mergers, tender offers, and similar transactions, which are typically covered in financial publications. 3. Asset-Conversion Opportunities: This includes various corporate transformations like distressed security exchanges, bankruptcies, and recapitalizations, often flagged in specialized industry reports and SEC filings. Identifying undervalued securities not fitting neatly into these categories often hinges on traditional methods; it requires effort and an analytical mind. Investors might scour the stock listings for significant decline percentages or analyze companies that recently cut dividends, as these situations may lead to overlooked investment prospects. Sometimes, attractive investment niches arise over time, such as the wave of thrift institutions converting to stock ownership. Investigating all companies within such categories can reveal lucrative prospects which specialized newsletters and industry publications can effectively illuminate. Once apparent bargains are identified, the next step is to explore the underlying reasons contributing to the price discrepancies. Economically cautious investors often approach unexpected low prices with skepticism, much like one would question an unusually low-priced home. A keen investor would seek to understand whether irrational selling or deeper issues, such as legal liabilities or competitive threats, are driving the price down. Identifying isolated causes for low valuations not only provides clarity but can also present richer investment opportunities. Market inefficiencies create fertile ground for value investors. These inefficiencies occur when information is not fully disseminated or supply and demand are misaligned, often evident with small, obscure companies that lack continuous market coverage. Year-end tax selling exemplifies another situation leading to temporary price reductions, thus creating opportunities as stocks sell lower than their intrinsic worth. Acting as a contrarian is inherent to value investing. To locate promising investments, one must often look where the market is reluctant, finding opportunity in out-of-favor securities that the majority dismisses. However, adopting a contrarian viewpoint can be challenging, as early positions may lead to initial losses while market trends persist. The danger lies in holding contrary views that do not substantiate actual value discrepancies. Successful contrarians must identify when majority opinion creates favorable odds by pushing prices of undervalued securities even lower. In the research process, striving for perfect knowledge can be counterproductive. Investors must accept that every variable cannot be known, and high uncertainty may correlate with low prices. Prudent decisions based on incomplete data can yield significant rewards, whereas waiting for certainty often results in lost opportunities. A valuable insight comes from observing insider buying activities, as management typically possesses deeper insights about the company's prospects. When corporate insiders invest their own money, it can signal confidence in the business's future, presenting potential gains for outside investors. Monitoring management’s actions, particularly those linked to stock incentive paths, can illuminate underlying motivations that might bring stock prices more in line with their perceived value. Understanding the interplay between public and insider information complicates investment decisions. The distinction between legal boundaries of information acquisition often exists ambiguously, complicating the paths investors tread to unearth actionable insights while complying with regulations. In conclusion, effective investment research involves filtering through vast amounts of information to distill actionable intelligence. The success of an investment strategy relies on the ability to conduct rigorous ongoing research, recognizing that immediate buying opportunities might not arise from any single analysis, but rather prepare investors for future market movements. High-quality research, much like a manufacturing process, is essential for translating valuation insights into directed portfolio strategies, underscoring the commitment required for successful investing over time.

Chapter 10 | Areas of Opportunity for Value Investors: Catalysts, Market Inefficiencies, and Institutional Constraints

The allure of value investing often stems from identifying profitable and growing businesses whose share prices are significantly undervalued relative to a conservatively assessed intrinsic value. However, such rewarding opportunities are typically rare, as the more straightforward the analysis and the steeper the discount, the more likely they are to attract attention from a broader pool of investors. As a result, high-return businesses only reach compelling levels of undervaluation infrequently. Value investors must often delve deeper into intricate situations or unearth hidden values to uncover promising investments. Once a security is purchased at a discount, the potential for immediate gains arises if the stock price rises to reflect its intrinsic value or if specific events occur that facilitate the realization of that value, known as catalysts. Catalysts can be internal, driven by management decisions such as liquidation or restructuring, or external, often influenced by market control dynamics. Major ownership concentration allows stockholders to exert influence over board elections, potentially leading to corporate actions that align share prices with intrinsic value. Catalysts can vary in strength; complete liquidation of a company leads to total value realization, while actions such as share buybacks or spinoffs tend to provide partial realization. For instance, creditors in a bankruptcy scenario often receive higher distributions than the distorted market value of their debts, underscoring the importance of understanding capital structures during reorganizations. The search for catalysts is paramount for value investors, as they provide a framework through which the risks associated with market fluctuations can be mitigated. The prompt realization of underlying value reduces the likelihood of significant losses, providing a stronger margin of safety. While total realization is preferable, even partial realizations can signal management’s commitment to enhancing shareholder value, paving the way for future opportunities. Investing in distressed corporations that opt for liquidation presents a unique angle for value investors. Companies may liquidate to prevent complete losses, often driven by factors like tax benefits or persistent undervaluation by the market. When such companies liquidate, identified assets can frequently be valued more favorably compared to ongoing businesses, creating unique opportunities. The City Investing Liquidating Trust exemplifies such a case. After voting to liquidate in 1984, shareholders received shares in a newly formed trust comprising diverse, undervalued assets, including notable investments that had been overlooked by most investors. The trust initially traded at a significant discount due to market apathetic tendencies and investor disenchantment but soon appreciated in value as assets began to be liquidated effectively. Complex securities, characterized by unique cash-flow structures dependent on contingent events, also present intriguing opportunities for value investors. These securities often go unnoticed due to their complexities, allowing discerning investors to find undervalued assets that could yield attractive returns. Historical examples illustrate that even unfamiliar or obscure securities could enhance a portfolio if understood and valued correctly. Rights offerings emerged as yet another niche for value investors. Unlike traditional share offerings, rights offerings allow existing shareholders to maintain their percentage ownership, potentially leading to attractive investments for those willing to exercise their rights amid dilution risks. Failures to act can enable value investors to capitalize on unforeseen market opportunities where others might recoil due to a lack of knowledge or interest. In the realm of risk arbitrage, the landscape is heavily influenced by market cycles. As this specialized investment area grows in popularity, increasing competition may diminish potential returns, creating a natural cycle of peaks and troughs in investment performance. Those who remain in the field during challenging times often find greater opportunities arise as market participants exit. Spinoffs also constitute a favorable hunting ground for value investors. The initial distribution of a subsidiary to a parent company’s shareholders may lead to irrational selling patterns driven by misinformation or underappreciation of the spun-off entity’s potential. Investors exodus can provide low entry points for discerning buyers, as exemplified by cases where spinoffs initially traded below their intrinsic values. This chapter serves as a reminder that various market niches continually produce opportunities for keen value investors. The discussion highlights that numerous avenues exist where inefficiencies can emerge, allowing astute investors to capitalize on unrealized value. Future chapters aim to further delve into specific sectors ripe for value investment, reinforcing the idea that while challenges persist, they often pave the way for lucrative investment opportunities.

Key Point: The importance of identifying and acting on catalysts in investments.

Critical Interpretation: Imagine approaching life with the same keen eye for opportunity as a value investor seeks out catalysts in undervalued stocks. Just as they recognize that the right management decision or market shift can unlock significant value, you too can look for those moments in your own journey. Whether it’s pursuing a passion project, changing careers, or taking risks in your personal growth, acknowledging catalysts—those pivotal decisions or events that can transform your path—can lead to remarkable advancements. Life is filled with moments where your intrinsic value can shine; all it takes is the courage to act upon those catalysts when they appear, turning potential into tangible success.

Chapter 11 | Investing in Thrift Conversions

Mutual thrift institutions, originating in the mid-nineteenth century, have evolved significantly over the years, leading to a myriad of opportunities for value investors, particularly after the wave of conversions to stock ownership since 1983. This shift was markedly catalyzed by a combination of negative publicity and the adverse economics stemming from thrift conversions, which led to depreciated share prices across many thrifts. Historically, thrift executives enjoyed the simplicity of managing these institutions, dictated by the 3-6-3 principle—gaining deposits at 3 percent, lending them out at 6 percent, and enjoying leisure time by 3 o'clock. However, deregulation in the late 1970s thrust many thrift institutions into financial turmoil. This new landscape forced these institutions to contend with fluctuating interest rates that rendered their fixed-rate assets unprofitable, leading to an unsustainable imbalance between liabilities and assets. By the 1980s, the ramifications of deregulation, coupled with the uneven application of the Garn-St. Germain Act of 1982 that encouraged risky lending, resulted in enormous losses for many thrifts. Consequently, a severe liquidity crisis ensued, leaving only well-capitalized thrifts capable of converting to stock ownership and taking advantage of initial public offerings (IPOs). Unlike a standard IPO, where insiders could profit at the expense of public investors, thrift conversions offered a unique proposition: the value added from the publicly issued shares directly contributed to the institution’s total net worth. Thus, potential investors effectively bought equity alongside the institution's existing assets, often yielding compelling investment opportunities. To elaborate, during a mutual-to-stock conversion, depositors have the first right to purchase shares, alongside management. Any remaining shares are offered to the public, and this framework ensures that investors are buying into a potential increase in value. This distinctive feature means that in the case of a successful conversion, investors stand to gain significantly if the thrift has inherent positive business value pre-conversion. However, caution is warranted; not all thrifts possess greater values than their stated book prices, and many may be operating at a loss, which could hinder future growth. The depressed stock prices of thrifts throughout the 1980s can be attributed in part to a lack of analytical coverage from Wall Street. Only a handful of analysts covered the few largest public thrifts, resulting in new thrift conversions often being issued at substantial discounts compared to other publicly traded thrifts. Fundamental investment analysis remains crucial in evaluating thrifts, as institutions engaging in high-risk ventures or complex financial instruments should be avoided. A prudent rule of thumb for investors is to shy away from any entity whose operations are not readily comprehensible, as this might reflect a lack of clarity from management regarding their own strategies. Investors should employ conservative valuation practices, particularly in evaluating leveraged financial institutions. Given that many thrift takeovers occur above book value, it is essential to adjust stated book values to account for a range of inflating and deflating factors such as under- or over-stated assets and liabilities. Adjustments are also necessary when evaluating earnings, ensuring that investors focus on recurring income rather than sporadic gains. Thrifts with low overheads are generally more favorable due to their enhanced profitability and adaptability during challenging financial climates. Despite the compelling nature of thrift conversions, they remain fraught with inherent risks, underscored by varying asset quality, interest rate fluctuations, and external competitive pressures. Each potential investment must be meticulously analyzed on a case-by-case basis, rather than as part of a larger trend. A pertinent case study exemplifying these principles is the Jamaica Savings Bank's conversion to stock ownership in 1990. Amidst a national real estate downturn and widespread market panic, Jamaica Savings Bank (JSB) stood out with robust capital ratios and minimal credit risk due to its asset composition. Investors were invited to purchase shares at attractive valuations—indeed, significantly below book value—because the wider market was still distressed. Despite the gloomy economic backdrop, the solid financial foundation and proactive management made JSB an appealing opportunity, showcasing how even within tumultuous markets, astute investors could find value. As illustrated by JSB's conversion and subsequent success, thrift conversions represent a noteworthy segment of the financial landscape, underlining the impact of investor behavior and the importance of thoughtful analysis. While often ignored, this niche offers rich opportunities for those who are persistently willing to delve into the intricacies of thrifts and their unique investment dynamics.

Chapter 12 | Investing in Financially Distressed and Bankrupt Securities

Investing in financially distressed and bankrupt securities has long been associated with a stigma due to their perceived risks. These investments, however, can provide opportunities for those willing to conduct thorough analysis amidst the complexities and nuances of the reorganization processes. 1. Understanding Financial Distress: Companies find themselves in financial trouble for various reasons including operational failures, legal issues, and significant debts. Financial distress often translates to inadequate cash flow, leading to an inability to meet obligations, thus catalyzing a cascade of challenges such as loss of suppliers and staff. The impact of financial distress varies widely among sectors, with capital-intensive industries being somewhat resilient compared to those reliant on public trust or image. 2. Value Opportunity in Distress: Given that many investors shy away from distressed securities, such investments often trade at substantial discounts relative to par, presenting attractive opportunities for those with expertise and patience. These securities, unlike newly issued junk bonds, reward strong fundamental analysis and risk assessment. 3. Issuer Strategies for Debt Management: Companies facing distress typically have three main pathways: maintaining their obligations, offering exchange deals on securities, or opting for bankruptcy. Successfully navigating these options depends heavily on the underlying cause and the strategic responses of the management. Alternatives such as cost-cutting or capital infusions may stave off bankruptcy temporarily, but they risk long-term viability. 4. The Bankruptcy Mechanism: A bankruptcy filing triggers an automatic halt to creditor collection efforts, shifting the focus to negotiating a plan of reorganization. Conflicts often emerge between the interests of debtors wanting to rebuild and creditors seeking maximized cash returns. Under Chapter 11, companies may restructure debts, reject leases, and close unprofitable operations to emerge as streamlined competitors. 5. Opportunities and Risks in Bankruptcy Investing: Three distinct stages characterize the bankruptcy investing landscape. The first involves the uncertainty post-filing; the second stage focuses on negotiations for a reorganization plan, and the final stage sees a company's emergence and the accompanying liquidity events for creditors. Each stage offers unique investment potentials, with the first stage often presenting the highest risk and reward. 6. Challenges of Distressed Investing: Although investing in financially troubled companies can yield substantial returns when done correctly, it requires a keen understanding of the risks involved. The speed and timing of financial recovery are critical, and the market dynamics can vary importantly by sector. Investors must diligently analyze a company's balance sheet while also assessing any off-balance-sheet assets or liabilities that could affect recoveries. 7. Effective Investment Strategy: To invest successfully in distressed securities, one must deeply analyze both assets and liabilities, considering claims by priority. Understanding the capital structure is crucial, as holders of 'fulcrum securities' – those that occupy a midpoint in seniority – may experience the highest return potentials when valuations improve. Conversely, common equity in bankrupt companies is usually a dangerous gamble. 8. Real-Life Case Studies: The chapter presents examples such as Harcourt Brace Jovanovich and Bank of New England to illustrate the market dynamics between distressed bonds and stocks. These instances highlight how mispricing can occur between different security classes, allowing savvy investors to exploit discrepancies through arbitrage strategies. 9. Conclusion and Insights: Ultimately, investing in distressed securities is a sophisticated endeavor that demands in-depth analysis and a tolerance for the complexities that accompany financial restructuring. While the uniqueness and complications involved may deter many investors, those who succeed in identifying mispriced opportunities can find substantial value in these overlooked assets. The chapter emphasizes the necessity for concerted research and critical assessment to uncover attractive investment avenues in unpredictable markets.

Key Point: Embrace Complexity to Uncover Value

Critical Interpretation: Just as investing in distressed securities requires you to delve into the intricate details of financial struggles, your life can similarly benefit from embracing complexity rather than shying away from it. By examining the challenges you face, whether personal or professional, you can discover hidden opportunities for growth. When you look beyond the surface, assessing the full context of situations, you may find insights that can lead to profound transformations. This chapter teaches you that thorough analysis and a willingness to engage with the difficult aspects of life can reveal potential that is easily overlooked, empowering you to take calculated risks and pursue endeavors that others deem too risky.

Chapter 13 | Portfolio Management and Trading

In the landscape of investing, trading and portfolio management stand out as critical components that can significantly influence an investor's total returns. Trading involves the buying and selling of securities, which can enhance profitability or impact the effectiveness of executing trades. Effective portfolio management encompasses regular assessments of holdings, ensuring adequate diversification, making informed hedging decisions, and managing liquidity and cash flow. Unlike finite business ventures, portfolio management is a continuous process, evolving with market conditions and investor strategies. 1. Recognizing the Continuity of Portfolio Management: Investors must accept the ongoing nature of portfolio management. Unlike businesses with predictable sales and a history of profitability, market investments lack guaranteed outcomes. The potential benefits investors reap depend on the price they pay for their assets as much as on the performance of the underlying businesses. 2. Understanding Liquidity: Liquidity plays a vital role in investment decisions, allowing for the flexibility needed to adapt to market changes. An investor in liquid securities can easily adjust positions without significant financial repercussions, whereas those in illiquid investments may find themselves effectively locked into commitments. Generally, maintaining a balance between liquid and illiquid investments is advisable, as unexpected liquidity needs can arise. The risk of illiquidity is exacerbated by duration—the longer an asset is expected to remain illiquid, the greater the compensation investors should demand. 3. The Illusion of Liquidity: Liquidity can be misleading, often seeming abundant during stable markets but disappearing during downturns. Investors must be prepared for the reality that even if they can sell, collective market conditions may impact overall liquidity. Consequently, maintaining a diverse portfolio broader than fashion-driven sectors can be crucial during market shifts. 4. Navigating the Tension between Risk and Return: Investing inherently involves trade-offs between potential returns and risks. Cash investments carry no risk of loss but yield low returns, creating a dilemma for investors torn between retaining liquidity for future opportunities and pursuing higher returns through less liquid investments. This cycle of cash and investments perpetuates a dynamic interplay between managing portfolio liquidity and optimizing returns. 5. The Importance of Diversification: To mitigate downside risk, investors must embrace diversification, though wisdom dictates that it should not be done excessively. Holding ten to fifteen varied securities typically suffices for risk reduction, allowing for in-depth understanding of each holding. Over-diversification can dilute knowledge and investment focus—successful investors prioritize quality over quantity in their holdings. 6. Strategic Hedging: Market risk cannot be mitigated by diversification; hence, hedging becomes a valuable tool. Investors can employ various strategies tailored to their specific holdings, from utilizing index futures for broad market exposure to hedging industry-specific stocks through appropriate channels. While effective, hedging must be judiciously considered; its costs and complexity warrant careful evaluation against potential returns. 7. Recognizing the Role of Trading: Trading is essential for capitalizing on price misallocations resulting from market inefficiencies. Value investors thrive when others pay too high or sell too low, converting market dynamics into favorable opportunities. Thus, staying connected with market changes augments the potential for successful trading—abstaining from monitoring market activity can lead to missed opportunities. 8. Developing a Trading Mindset: Investors must approach price fluctuations with rationality, resisting the dual temptations of panic during price declines and euphoria during rises. It is prudent to refrain from committing to a full purchase immediately, retaining the capacity to average down on declining prices if necessary. This approach can help distinguish genuine investments from speculative ventures. 9. Selling Strategies: When it comes to selling, the challenge lies in knowing when to act based on shifting values. Many investors employ rigid rules for selling, like specific price targets, but flexibility is crucial. The optimal time to sell should align with available alternatives and market dynamics rather than strict personal criteria. Understanding liquidity at the time of sale is also paramount; a thorough comprehension of market depth influences decisions about when to exit an investment. 10. Cultivating Relationships with Brokers: Engaging with the right broker can significantly affect investment success. Long-term relationships with brokers who prioritize client interests over transaction volume foster beneficial partnerships. Investors should seek capable brokers who recognize the importance of personalized service, thus ensuring that their investments receive the attention they deserve. In sum, managing one's investment portfolio effectively hinges not only on sound trading and portfolio management strategies but also on a value-investor mindset. By merging astute buying and selling practices, dynamic portfolio adjustments, and thoughtful diversification and hedging, investors can navigate the complexities of the market while striving for sustainable returns.

Chapter 14 | Investment Alternatives for the Individual Investor

In exploring the challenges faced by individual investors, it becomes evident that the landscape of investment options is fraught with pitfalls. Investing is a demanding full-time endeavor, requiring substantial dedication and effort. With a treasure trove of information at one's disposal, achieving lasting success through occasional or part-time engagement is highly improbable. Those who find it difficult to commit the necessary time will generally lean towards mutual funds, discretionary stockbrokers, or money managers as their preferred alternatives. 1. Mutual Funds as a Viable Option Ideally, mutual funds should present a compelling choice for individual investors, offering professional management along with benefits such as low transaction costs and immediate liquidity. However, in reality, the performance of most mutual funds leaves much to be desired, with only a handful truly standing out. It is advisable to choose no-load funds over load funds, as the latter imposes a hefty upfront fee that rewards sales commissions rather than performance. Open-end funds are typically more attractive to investors compared to closed-end funds since their share prices directly correlate with the net asset value of underlying holdings. Unfortunately, many fund managers are under pressure to chase short-term performance metrics, compromising their potential to deliver long-term value to investors. 2. Trends in Mutual Funds The emergence of speculative “hot” money in open-end mutual funds has further complicated matters. Types of mutual funds aimed at capitalizing on trending markets cater to investors looking for quick profits, enticing them through aggressive marketing strategies. Conversely, select funds focused on long-term value investment, such as the Mutual Series Funds and the Sequoia Fund, distinguish themselves by cultivating a base of loyal investors, thereby mitigating the risk of forced liquidations during downturns. 3. Choosing Discretionary Stockbrokers and Money Managers When it comes to selecting discretionary stockbrokers or money managers, recognizing potential conflicts of interest is crucial. Both roles entail a fiduciary duty, and prospective clients must engage in thorough inquiries regarding ethical practices and transparency in client treatment. The evaluation should consider whether managers manage personal funds alongside client funds, which could reflect their belief in their strategies. 4. Evaluating Investment Strategies Investment success relies heavily on the philosophy guiding the stockbroker or money manager. It is important to ascertain their commitment to absolute returns versus relative performance, and to ensure they employ intelligent, long-term strategies that are devoid of arbitrary constraints. 5. Assessing Past Performance Before entrusting funds to any manager, an examination of their historical performance is paramount. Critical questions should revolve around the length and consistency of their track record across varying market conditions, the nature of their investment decisions, and whether their approach has consistently aligned with risk management principles. It is wise to discern how much of their success is attributable to skill versus luck, while also factoring in the significance of personal rapport with the chosen manager. 6. Ongoing Evaluation Once a money manager is selected, continued vigilance regarding their investment behavior and results is essential. The principles guiding your initial hiring decision should continue to be relevant long after the relationship is established. In conclusion, as investors venture beyond the safety of U.S. Treasury bills, it is vital to adopt a conscious, engaged approach to investment. The imperative is to either stay informed and committed to a value-investment philosophy or to seek out a talented investment professional embodying such a philosophy. Ultimately, every decision carries risk, and inaction is a decision in itself—a reality that all investors must acknowledge.