Last updated on 2025/05/01

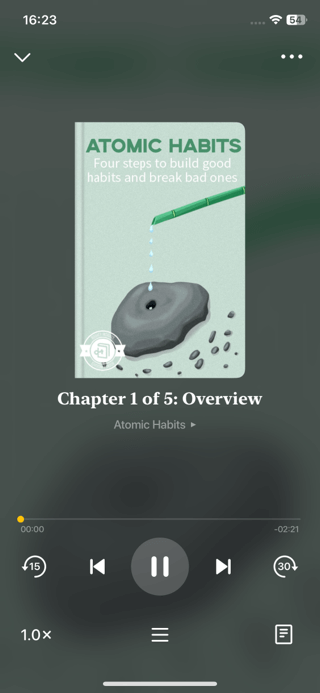

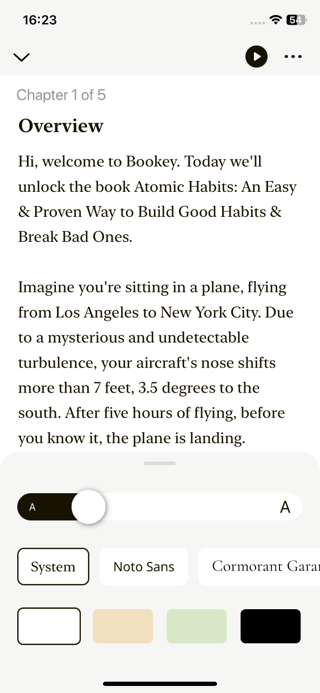

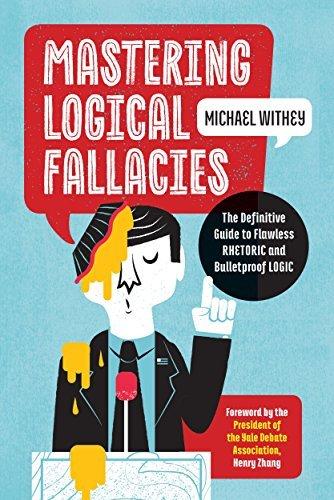

Mastering Logical Fallacies Summary

Michael Withey

Identify and Defend Against Flawed Arguments Effectively.

Last updated on 2025/05/01

Mastering Logical Fallacies Summary

Michael Withey

Identify and Defend Against Flawed Arguments Effectively.

Description

How many pages in Mastering Logical Fallacies?

191 pages

What is the release date for Mastering Logical Fallacies?

In an age where information is abundant and persuasive arguments shape our beliefs, "Mastering Logical Fallacies" by Michael Withey serves as an essential guide to navigating the treacherous waters of reasoning. This insightful book demystifies the complexities of logical fallacies—those sneaky errors in reasoning that can undermine the strength of any argument—empowering readers to identify and combat flawed logic in everyday discussions. Through engaging examples and practical strategies, Withey not only illuminates the common pitfalls of argumentation but also enhances critical thinking skills essential for effective communication. Dive into its pages to sharpen your analytical prowess, foster intellectual honesty, and become a master of sound reasoning in an increasingly debate-driven world.

Author Michael Withey

Michael Withey is a noted author and educator with a strong focus on critical thinking and logical reasoning. With a robust academic background and extensive experience in philosophy, Withey has dedicated his career to helping individuals enhance their argumentative skills and recognize common pitfalls in reasoning. His work, particularly in "Mastering Logical Fallacies," reflects his passion for fostering intellectual rigor and clarity in communication. Through relatable examples and a comprehensive approach, Withey aims to equip readers with the necessary tools to identify and counteract logical fallacies in everyday discourse, ultimately encouraging more thoughtful and productive conversations.

Mastering Logical Fallacies Summary |Free PDF Download

Mastering Logical Fallacies

chapter 1 | AD HOMINEM: ABUSIVE

In the exploration of logical fallacies within the realm of argumentation, this chapter delves into the nature, identification, and implications of various forms of ad hominem fallacies, along with supplementary logical missteps. The discussion is rich in examples, both historic and contemporary, vividly illustrating how personal attacks and misdirected reasoning can undermine rational discourse. 1. The ad hominem fallacy, characterized by its focus on attacking a speaker rather than the argument presented, surfaces in various forms. For instance, when Person A asserts that P, and Person B responds by disparaging A’s character rather than addressing the claim, the argument falls into a logical pitfall. A historical example involves Cicero, who faced personal jabs regarding his humble origins during legal disputes rather than the content of his arguments. This tactic illustrates that undermining the character of a person does not affect the truth of their claim, whether that claim concerns scientific phenomena or social policies. 2. The significant error in ad hominem reasoning is its irrelevance; criticizing the character of the speaker does nothing to validate or invalidate the argument being made. In answering such attacks, a rational approach involves redirecting the conversation back to the argument itself, thereby illuminating the logical fallacy at play. Unfortunately, in practice, these personal attacks can be persuasive and damage reputations regardless of their logical grounding. 3. Circumstantial ad hominem arguments further complicate matters by discrediting an argument based on the proponent’s circumstances, such as motives tied to vested interests. For example, a CEO advocating for an oil drilling project could be readily dismissed due to presumed biases stemming from financial gain. However, the truth of the argument remains unaffected by the personal stakes of the speaker. When faced with such arguments, it is crucial to present objective evidence supporting the claim to counteract unjust skepticism. 4. Guilt by association emerges as another form of ad hominem reasoning, where the validity of a claim is questioned based on disreputable figures associated with it. In this situation, the focus again shifts away from the merits of the argument itself toward the character of those involved in advocating it. Historical examples, such as political candidates facing scrutiny for their associations, underscore the ineffectiveness of this logic. A stronger rebuttal involves insisting that the focus remain on the argument’s validity rather than the company one keeps. 5. The tu quoque fallacy exemplifies another ad hominem variant, wherein a speaker’s argument is dismissed because they indulge in the very behavior they critique. This reasoning is flawed as it suggests that sincerity is inherently linked to one’s actions, when in fact the tenets of an argument can stand apart from the speaker’s personal conduct. A response involves emphasizing the distinction between behavior and belief, allowing for an acknowledgment of weakness without compromising the argument’s validity. 6. Shifting to formal fallacies, the mistake of affirming the consequent highlights the pitfall of inferring a direct correlation between a condition and its outcome. An incorrect conclusion may be drawn, as seen in examples like the logic behind a nonexistent Bear Patrol suggesting its effectiveness solely based on the absence of bears. Recognizing such logical flaws allows one to redirect the discussion toward valid reasoning. 7. Ambiguity plays a vital role in logical discourse, manifesting itself through the equivocation of terms, where a word or phrase takes on different meanings in varied contexts, thus rendering arguments invalid. The chapter provides illustrations, including scenarios devised by Plato, showcasing how inconsistencies lead to faulty conclusions. Addressing ambiguity requires the clarification of terms and restructuring arguments to eliminate confusion. 8. Lastly, the idea of authoritative voice becomes relevant in discussions of anonymous authority. The crux is that an argument's foundation should rest on evidence and rationality rather than the credentials or notoriety of its proponent. Asserting claims based on anonymous expertise leads to ad hominem reasoning, emphasizing the need for arguments to stand on their own merit rather than on authority alone. This chapter serves as a robust examination of logical fallacies, serving to reinforce the importance of assessing arguments based on their intrinsic merits rather than extraneous personal attributes or misleading associations. Understanding these principles enables individuals to engage more effectively in reasoned discourse, minimizing the impact of fallacious reasoning.

Key Point: Recognizing the detachment of arguments from personal character.

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing in a heated debate, where someone attacks you personally instead of engaging with your ideas. This chapter empowers you to rise above such distractions. By recognizing that the quality of an argument stands independent of who presents it, you gain the strength to refocus discussions on their inherent merits. This not only sharpens your reasoning skills but also fosters a more respectful discourse, ultimately inspiring you to pursue truth and understanding, while maintaining your integrity amidst the chaos of ad hominem attacks.

chapter 2 | ANONYMOUS AUTHORITY

In the exploration of logical fallacies, several informal arguments emerge that challenge the integrity of reasoning through appeals to authority, emotion, popularity, and desperation. These fallacies illustrate the pitfalls in argumentation and emphasize the need for critical thinking when evaluating claims. 1. Argument from Anonymous Authority highlights the fallacy in which a proponent justifies a claim by invoking an undefined authority. An example is someone stating, “Experts say gluten is harmful,” without identifying any specific expert. This type of argument is flawed because without verifying the authority’s credentials, the legitimacy of the argument collapses, allowing for people to misrepresent their claims without accountability. To counter such a claim, one might ask the proponent to clarify who these experts are and what their qualifications consist of. 2. Argument from Anger (Argumentum ad Odium) demonstrates how an argument can exploit the audience's emotions, particularly anger, to discredit a position simply because it offends them. For instance, one might reject immigration policies based on emotionally charged sentiments rather than reasoned analysis. It is essential to recognize that emotional responses do not negate factual truth; thus, engaging in rational discourse and urging a more compassionate perspective serves as a more effective counterstrategy. 3. Argument from Authority (Argumentum ad Verecundiam) involves supporting a claim by referring to someone regarded as an authority figure. For example, claiming that evolution is false because one’s father believes it to be so lacks substantial grounding in actual expertise. While citing expert opinions can be a useful practice, it is crucial to verify the relevance and authority of the cited individual to the matter at hand. Challenging the credibility of the authority and seeking broader consensus in the relevant field provides a robust comeback to this fallacy. 4. Argument from Celebrity questions the validity of arguments based solely on the endorsements of famous individuals. The reasoning that eating peas is harmful because a well-known actress said so showcases a fallacy; expertise is not automatically conferred by fame. Responding to this argument requires questioning the knowledge base of the celebrity on the subject, as credibility derives not from popularity but from expertise in the relevant area. 5. Argument from Common Belief (Argumentum ad Populum) asserts that because many people believe something to be true, it must be so. This reasoning can be misleading, as demonstrated by the storied belief that the sun revolves around the Earth. The mistake lies in assuming that collective belief is synonymous with truth. Counteracting this fallacy necessitates presenting evidence or expert opinion that contradicts popular belief, thereby revealing the fallacies that exist when assumptions go unchallenged. 6. Appeal to Desperation (The Politician’s Syllogism) arises when a proposed solution is presented for a problem, regardless of its effectiveness. A common narrative in political discussions encapsulates this fallacy, where action is demanded simply because something must be done, irrespective of the appropriateness of the proposed action. For instance, suggesting an increase in the Medicare eligibility age in response to budget deficits disregards more effective alternatives. Critiquing this logic involves highlighting the ineffectiveness of the proposed solution and advocating for more viable solutions. Overall, while emotions and popular beliefs can sway opinions, they do not substitute for logical reasoning. Acknowledging the limits of authority, credibility, and emotional appeal is vital in fostering sound arguments and ensuring that discussions based on fallacies are correctly identified and appropriately challenged. By enhancing our critical thinking skills, we become better equipped to separate facts from fallacies, leading to more informed discussions and decisions.

Key Point: Recognizing Logical Fallacies Enhances Critical Thinking

Critical Interpretation: Imagine navigating life's myriad of challenges equipped with the ability to discern truth from manipulation. By recognizing arguments from authority, emotion, and common belief, you empower yourself to question claims that may initially seem convincing but lack solid footing in reality. When someone says, 'Experts agree', your instinct becomes to ask who these experts are and what makes their opinion credible. This critical approach not only bolsters your reasoning but also encourages those around you to engage in deeper, more meaningful discussions. In this way, every conversation you partake in can become an opportunity for enlightenment, helping you make informed decisions and fostering a culture of accountability and truth-seeking in your community.

chapter 3 | APPEAL TO EMOTION

Chapter 3 of "Mastering Logical Fallacies" by Michael Withey delves into various informal fallacies, particularly focusing on emotional appeals and their implications in discourse. The analysis presents several key types of arguments that may appear persuasive but fail under scrutiny. 1. The Appeal to Emotion involves a proponent arguing for or against a conclusion by invoking emotional responses instead of addressing the central issue. This method manipulates audience feelings, rendering rational discourse practically impossible. For instance, advocating against welfare cuts by evoking sentiments of cruelty illustrates how emotional manipulation may overshadow logical reasoning. While emotional appeals can be powerful motivators for action, their use must not replace logical arguments, as the underlying facts remain steadfast despite emotional reactions. When countering such arguments, it may be more effective to also employ emotional appeals to present one's stance as a means to alleviate greater suffering than that proposed by the opponent. 2. The Appeal to Faith argues that a belief is true solely based on faith, disregarding evidence or reasoning. An example includes the assertion that one need not abandon harmful habits due to blind trust in divine protection. Faith-based arguments can be potent among followers of similar beliefs, but they lack universal applicability, as they fail to convince those outside that belief system. In responding, one can highlight the absence of sound reasoning in the opponent's argument or even utilize shared faith principles to undermine their rationale. 3. The Appeal to Fear employs intimidation to support a conclusion by manipulating an audience's anxieties. For instance, a political leader might provoke fear to justify a policy without providing factual grounding. The allure of such arguments lies in their ability to bypass logical analysis, relying instead on the audience's emotions. A sound strategy against these arguments involves debunking the baseless fears presented or providing evidence that contradicts the exaggerated threats, thereby restoring rational debate. 4. The Appeal to Heaven posits that divine approval establishes the legitimacy of an action. This reasoning raises questions about the interpretation of divine will and its application to justify actions, sometimes leading individuals to commit morally questionable acts while claiming divine endorsement. The key comeback to this argument is to expose its reliance on faith, calling into question the credibility and validity of the supposed divine command. This invokes the Euthyphro Dilemma, which challenges the foundation of moral decisions based on divine approval alone. 5. The Appeal to the Moon suggests that because one person or society has achieved a remarkable feat, another should be able to accomplish something similarly impressive. This fallacy does not respect the fundamental differences in context and challenges inherent between the two accomplishments. To effectively counter this line of reasoning, one must highlight the distinct challenges associated with each feat, demonstrating that prior success does not guarantee the feasibility of new endeavors. In summary, the exploration of these fallacies illustrates the intricate play of emotion, belief, fear, divine will, and unlikely comparisons in argumentation. Each fallacy underscores the necessity of grounding discussions in sound reasoning and factual evidence, thereby fostering a more rational exchange of ideas. Recognizing these fallacies not only enhances critical thinking but also empowers individuals to engage more effectively in debates and discussions.

Key Point: Awareness of Emotional Appeals

Critical Interpretation: By learning to recognize the Appeal to Emotion, you gain the power to navigate conversations with a nuanced understanding of how emotions influence decision-making and arguments. This insight empowers you to separate genuine concerns from manipulative rhetoric. You might find yourself questioning the emotional weight of arguments presented to you, prompting you to respond with logical reasoning rather than emotional reaction. In your daily interactions, this awareness can inspire you to approach discussions mindfully, relying on a balanced mixture of thought and feeling, ultimately leading to more constructive dialogues and deeper connections.

chapter 4 | APPEAL TO NATURE

In "Mastering Logical Fallacies," Michael Withey explores a variety of informal logical fallacies that can distort arguments and debates. These fallacies demonstrate how common reasoning errors can lead to faulty conclusions. Here’s a summary of key fallacies presented in chapter 4: 1. Appeal to Nature: This fallacy asserts that something is considered good simply because it is perceived as natural, or bad because it is regarded as unnatural. An example is the assertion that homosexuality is wrong because it is labeled "unnatural." The mistake lies in the flawed dichotomy that equates natural with good. Responding to this argument may involve challenging the implicit belief that natural equals beneficial, and questioning outdated distinctions drawn between what is considered natural and unnatural. 2. Appeal to Normality: This fallacy posits that something is good if it is deemed normal, while anything seen as abnormal is bad. For instance, a critique of someone's music preferences could insist that they are wrong for not enjoying mainstream hits. In addressing this fallacy, one can point out that popularity does not equate to quality or value, thereby advocating for the acceptance of individuality and diversity. 3. Appeal to Pity: This tactic involves justifying one's position through an emotional appeal to pity rather than logical reasoning. For example, a student may argue for an undeserved grade by invoking their personal struggles. The essential error is that emotions do not substantiate a logical argument. Counterarguments can highlight the irrelevance of emotional appeals in the context of factual correctness. 4. Appeal to Possibility: This fallacy makes a claim based on the mere possibility of an event occurring. For example, stating that because there’s a possibility it may rain tomorrow, it will certainly rain. The critical error here is assuming that possibility equates to probability. Addressing this requires illustrating that not all possibilities are likely to happen, emphasizing the distinction between potential and probability. 5. Appeal to Ridicule: Instead of offering substantive counterarguments, this fallacy undermines an opponent's position through mockery. An example includes sarcastically dismissing substantial proposals as trivial. The mistake lies in failing to engage with the actual argument. A robust response involves demanding a legitimate rebuttal instead of mere ridicule. 6. Appeal to Tradition: This involves arguing that something is correct or valuable simply because it has traditionally been upheld. For instance, asserting that women should remain in the home because that is what has historically been done ignores the relevance of current social values. The error in this reasoning is assuming that the passage of time adds validity. Responses should question the validity of harmful traditions. 7. Argument from Ignorance: This fallacy relies on the notion that a lack of evidence for a claim equates to proof of its opposite. For example, inferring aliens exist simply because there is no evidence disproving their existence represents a flawed logic. The critical flaw is equating absence of evidence with proof. A focused response asserts the importance of active inquiry rather than passive dismissal due to lack of evidence. 8. Base Rate Fallacy: This error occurs when general statistical rates are ignored in favor of specific data from a non-representative sample. For instance, assuming someone diagnosed with a rare disease is likely to have it based solely on a positive test result, without considering the low base rate of the condition among the general population. Addressing this fallacy requires an understanding of statistical principles and emphasizing the importance of representative data. 9. Begging the Question: This is a circular argument where the conclusion is assumed in the premises. For instance, saying that humans are always self-interested because all acts of kindness are actually selfish logically does not provide evidence. Identifying this fallacy requires highlighting the circular reasoning involved. 10. Biased Sample: This fallacy occurs when a conclusion about a population is drawn from a non-representative sample, such as claiming that all Americans believe in a certain ideology based on a survey from one specific group. A response to this must demonstrate the lack of representativeness in the sample used. 11. Blind Authority: Arguments based on the say-so of an authority figure without verification of their credibility represents a fallacious appeal to authority. Addressing this requires questioning the qualifications of the authority involved and presenting the need for substantiated expertise. 12. Cherry-Picking: This fallacy involves selecting only evidence that supports a specific conclusion while ignoring contrary evidence. For instance, claiming a treatment is effective based on a selective report of successes without acknowledging failures misrepresents the situation. The effective comeback involves demanding a comprehensive presentation of evidence. 13. Circular Reasoning: Closely related to begging the question, this fallacy asserts a claim that relies on itself for validation. For example, stating a leader's infallibility based on their claim of being infallible does not provide any grounding for trust. Identifying this requires demonstrating the reliance on self-reference without independent verification. 14. Complex Question: This fallacy is rooted in asking a question that presupposes certain facts that may not be accepted by the respondent, limiting their ability to answer accurately. An example would be asking someone if they have stopped a controversial behavior without acknowledging that they never engaged in it. The response should challenge the validity of the presupposition embedded in the question. 15. Equivocation: This fallacy arises from using a term with multiple meanings in a way that confuses the argument. For instance, a statement that exploits different definitions of "man" to draw a flawed conclusion showcases this error. The essential strategy for tackling it involves pointing out the ambiguous terms and clarifying their meanings. 16. Fake Precision: This occurs when quantitative evidence is presented more precisely than it is accurate. For example, making sweeping claims about crime rates without clear statistical support can mislead. A proper response should be to challenge the validity and methodology of the presented data. 17. Fallacy of Composition: This involves assuming that what is true for individual parts must also be true for the whole. An example might include asserting that if each member of a team possesses a certain skill, the entire team will have that skill. Addressing this fallacy requires demonstrating the complexity of how parts interact within wholes. 18. Fallacy of Division: The opposite of composition, this fallacy assumes that what is true of the whole must also be true of each part. An example would claim that because a group is privileged, all its members are privileged, ignoring individual circumstances. The comeback should clarify that group characteristics do not necessarily translate to every member. Through understanding these fallacies, individuals can sharpen their reasoning skills, enhance debates, and engage in more effective discussions. Each fallacy demonstrates the importance of critical thinking and the need for sound argumentation based on evidence and logic rather than emotional appeals or flawed premises.

chapter 5 | FALSE ANALOGY

Chapter 5 of "Mastering Logical Fallacies" by Michael Withey discusses several common logical fallacies that can undermine arguments and reasoning. The chapter covers the False Analogy, False Dilemma, Hasty Generalization, Just Because, Ludic Fallacy, Lying with Stats, and Magical Thinking fallacies, each with distinct characteristics and implications in argumentation. 1. False Analogy occurs when an analogy between two items, A and B, is improperly drawn. It follows a structure where both share a characteristic P, A has characteristic Q, leading to the conclusion that B must also possess Q. A real-life example discusses the comparison of electronic cigarettes to traditional cigarettes, ignoring the crucial differences in health impacts. The mistake here lies in assuming that because two cases are similar in one aspect, they must be similar in all significant aspects. To counter this, one must demonstrate the critical dissimilarities that invalidate the analogy. 2. False Dilemma presents a situation where only two options are available, despite the existence of other viable alternatives. This fallacy restricts the discussion to two exclusive choices, ignoring possibilities like option R or the acceptance of both options. An example includes a simplistic binary about marital status, where being unmarried does not equate to being a bachelor. Challenging this fallacy involves illustrating the existence of other options or a combination of options to highlight its limitations. 3. Hasty Generalization arises from drawing broad conclusions from too few examples. It infers that because a few instances of Group A exhibit property X, all instances must share this property. The example of an intelligent chicken observing that it always gets fed, until one day it is slaughtered, illustrates the flaw in reasoning based on insufficient data. To counter such reasoning, one must emphasize the need for a larger, more representative sample and consider other variables that could influence the observed property. 4. Just Because describes a situation where an assertion is made without any justification, relying solely on the authority of the speaker. An example features a command given without reason, exemplifying reliance on authority without supporting arguments. The comeback to this fallacy involves insisting on a rationale beyond mere assertion, emphasizing that claims should not be accepted without adequate justification. 5. Ludic Fallacy refers to the erroneous application of models derived from controlled environments to predict outcomes in the complex real world. An illustration features a martial artist who believes his dojo skills will translate to a street fight, overlooking uncontrolled variables. The mistake here is a misunderstanding of the applicability of models. To counter this fallacy, one must point out the limitations of models when confronted with the chaotic nature of real-life situations. 6. Lying with Stats involves the misuse of statistical data to support arguments misleadingly. For example, a comparison of state and private schools fails to account for the disproportionate number of each, leading to erroneously drawn conclusions. The central issue can often lie in arithmetic mistakes, inappropriate comparisons, or selective data presentation. The response requires a solid understanding of statistical principles to expose the manipulations present in the argument. 7. Magical Thinking links two unrelated events based on superstition rather than evidence. For instance, believing that finding a four-leaf clover brings good luck is an example of this fallacy. The reasoning assumes a causal relationship without scientific support. The comeback involves simply debunking these purported connections, emphasizing that correlation does not imply causation and pointing out the absence of empirical evidence for the claimed relationships. Overall, these fallacies significantly impact reasoning and debate, often leading to erroneous conclusions and misleading arguments. Recognizing and understanding them is crucial for effective communication and critical thinking. Each fallacy not only highlights common pitfalls in reasoning but also reinforces the importance of sound logic and evidence-based argumentation in discussions.

Key Point: Understanding and identifying the False Dilemma fallacy can inspire you to embrace a broader perspective in decision-making.

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing at a crossroads, where you feel pressured to choose between only two paths—one that seems safe and another that appears risky. This narrow view can stifle your choices and limit your freedom. However, if you recognize the False Dilemma fallacy, you can begin to see beyond this binary thinking, empowering you to explore a spectrum of possibilities. Realizing that there may be multiple options available can lead to innovative solutions and richer experiences in life, whether in career decisions, relationships, or personal growth. This awareness encourages you to question assumptions, seek alternatives, and ultimately make more informed, nuanced choices.

chapter 6 | MORALISTIC FALLACY

Chapter 6 of "Mastering Logical Fallacies" by Michael Withey delves into various informal logical fallacies, highlighting their characteristics, examples, and the implications of engaging in such reasoning. One of the key fallacies discussed is the moralistic fallacy, which posits that because something ought to be the case, it must be the case. This reasoning is illustrated through examples like the response to Darwinism, where moral sensibilities lead to the rejection of empirical evidence. It emphasizes that reality does not conform to our moral ideals, invoking a reminder of misplaced idealism. Another fallacy explored is the practice of moving the goalposts, where one party demands higher standards of evidence after initial standards have been met. This tactic undermines fair discourse, as it shifts the agreement on evidence mid-argument, rendering the discussion untrustworthy. The author suggests countering this behavior by highlighting the dishonesty in changing standards once an argument has been made. The chapter also details the multiple comparisons fallacy, where conclusions are drawn based on outlier data from multiple tests without adequate representation of the population. Through examples, it illustrates how this can lead to misconceptions about causation, underscoring the need for careful statistical analysis. The naturalistic fallacy is defined as equating natural properties with moral goods. The text clarifies that just because something occurs in nature does not mean it is inherently good or should be followed in societal contexts. The nirvana fallacy highlights situations where critics dismiss practical solutions because they do not achieve perfect outcomes. Withey recommends underscoring that incremental improvements are often better than achieving nothing due to perfectionism. Further falling in line with illogical reasoning is the non sequitur fallacy, where a conclusion does not logically follow the premises presented. The author encourages counterarguments by forcing the opponent to clarify their reasoning to highlight the disconnect. Proving nonexistence refers to the flawed argument that something must exist simply because it cannot be proven nonexistent, echoing the burden of proof principle that the assertion of existence lies on the proponent. Withey illustrates this with Bertrand Russell’s teapot analogy. The red herring fallacy diverts attention from the main argument by introducing irrelevant topics, while reductio ad absurdum misrepresents the opponent’s stance to discredit the argument. Relatedly, the reductio ad Hitlerum fallacy dismisses an argument by associating it with ideas or policies endorsed by Hitler or other despots, showcasing the logical fallacy of guilt by association. Lastly, the self-sealing argument and shoehorning techniques are presented, where one makes unfalsifiable claims or forces an unrelated agenda into a discussion. Both tactics undermine rational discourse by failing to engage genuinely with the topic at hand. Through an exploration of these fallacies, Withey emphasizes the importance of discerning valid reasoning from flawed logic, encouraging readers to approach discussions with clarity and rational thinking. Recognizing these common fallacies enhances the reader’s ability to engage in constructive debates and understand the dynamics of argumentative discourse.

Key Point: The Nirvana Fallacy

Critical Interpretation: When you find yourself overwhelmed by the imperfections of real-world solutions, remember the lesson from Withey’s discussion of the nirvana fallacy. It’s easy to fall into the trap of dismissing a good enough solution simply because it isn’t perfect. This is a powerful takeaway for your daily life, as it inspires you to appreciate incremental improvements and progress rather than waiting for an unattainable ideal. Whether it’s in your personal goals, relationships, or career aspirations, embracing the notion that small, tangible steps forward can lead to meaningful change allows you to foster resilience and hope, driving you to take action rather than succumbing to inaction due to unrealistic expectations.

chapter 7 | MORALISTIC FALLACY

In Chapter 7 of "Mastering Logical Fallacies" by Michael Withey, several key logical fallacies are explored, illustrating how arguments can be misconstructed and their implications can lead to flawed reasoning. The first fallacy discussed is the slippery slope, which posits that taking an initial action will lead to a cascade of negative consequences, often without substantiation. The reasoning behind this fallacy relies on an exaggerated chain of events, such as the claim that banning guns in certain situations will inevitably lead to complete gun prohibition. The critique of this fallacy encourages questioning the legitimacy of these supposed connections and challenging opponents to explain how one action leads to the feared outcomes. Additionally, while slippery slope arguments can sometimes reflect actual socio-political changes, they require thorough justification to be valid. Next, Withey introduces the special pleading fallacy, wherein a general principle is applied universally except in specific circumstances that the proponent wishes to exempt, without providing adequate justification. The critical response emphasizes the importance of consistency in applying rules, with the assertion that any exceptions must be duly supported. This fallacy invites discussions about fairness and the subjective nature of perceived exceptions. The spiritual fallacy appears as another example, wherein a claim, despite lacking evidence, is defended by redefining its success to align with spiritual or abstract criteria. This raises challenges regarding the epistemic validity of such claims, as verifying their truth becomes nearly impossible, blurring the line between genuine belief and evasion of accountability. The straw man argument entails misrepresenting an opponent's position to make it easier to attack, rather than addressing the actual argument. This technique fails to engage with the original claim and can lead to a superficial debate that obscures deeper issues, thus necessitating a clear articulation of one’s stance alongside a critique of the misrepresentation. Connected to decision-making psychology, the sunk cost fallacy occurs when individuals continue to invest in a failing endeavor due to previously invested resources. This approach often leads to further loss rather than rational reassessment based solely on future potential outcomes. The remedy involves recognizing sunk costs as irrelevant to future decisions, emphasizing the need for clarity in cost-benefit analysis. Unfalsifiability represents a significant concern in argumentative claims that cannot be proven wrong, deflecting any challenge to their validity. This principle, championed by philosopher Karl Popper, underscores the necessity for scientific claims to be testable and therefore falsifiable, maintaining a critical distinction between scientific inquiry and pseudoscience. Lastly, the use-mention error highlights a common confusion between discussing a word and the concept it signifies. This misinterpretation frequently arises in linguistic contexts, illustrating the importance of clear communication and understanding how language functions in conveying meaning. Taken together, these fallacies reveal the complexities of logical reasoning and the pitfalls that can derail discussions. Engaging critically with each fallacy encourages substantive dialogue and more robust conclusions in debates and arguments, striving for clarity and honesty in discourse.