Last updated on 2025/04/30

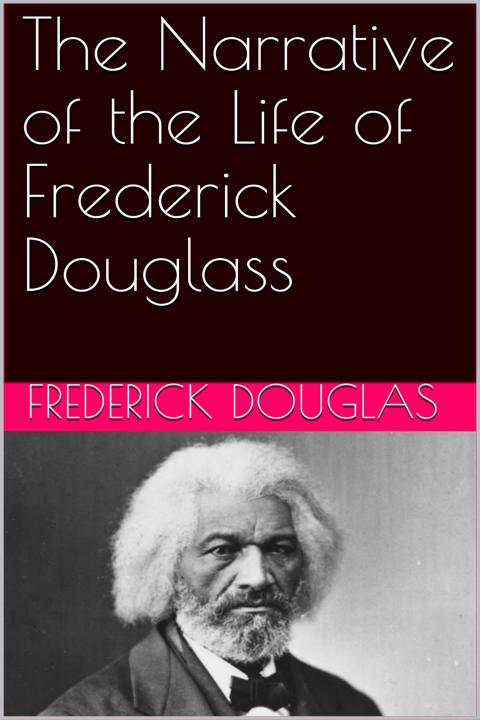

The Narrative Of The Life Of Frederick Douglass Summary

Frederick Douglass

A Journey from Slavery to Freedom and Empowerment

Last updated on 2025/04/30

The Narrative Of The Life Of Frederick Douglass Summary

Frederick Douglass

A Journey from Slavery to Freedom and Empowerment

Description

How many pages in The Narrative Of The Life Of Frederick Douglass?

212 pages

What is the release date for The Narrative Of The Life Of Frederick Douglass?

"The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass" is a powerful first-hand account of one man's relentless quest for freedom and dignity in a world marred by the horrors of slavery. Through Douglass's eloquent prose, readers are drawn into his harrowing experiences as an enslaved African American, witnessing the brutality of the institution that sought to dehumanize him. Yet, this narrative goes beyond despair; it is a profound testimony of resilience, intelligence, and the indomitable spirit of a man who not only escapes the bonds of slavery but also becomes a fierce advocate for emancipation and human rights. Douglass's story challenges us to reflect on the nature of freedom and the moral imperative to confront injustice, making it a vital read for anyone seeking to understand America's past and the ongoing fight for equality and human dignity.

Author Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass was an extraordinary orator, writer, and social reformer who emerged as one of the most influential voices in America during the 19th century. Born into slavery in February 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland, Douglass overcame the brutal conditions of his early life through perseverance and a relentless pursuit of knowledge. After escaping from slavery in 1838, he dedicated his life to the abolitionist movement, passionately advocating for the rights and dignities of African Americans and all oppressed people. His eloquent writings and powerful speeches, including his seminal work, "The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass," not only offer a poignant autobiography but also serve as a clarion call for equality and justice, challenging the moral foundations of slavery and racism in America.

The Narrative Of The Life Of Frederick Douglass Summary |Free PDF Download

The Narrative Of The Life Of Frederick Douglass

Chapter 1 | I Have Come to Tell You Something About Slavery: An Address

Frederick Douglass, in his powerful address delivered in Lynn, Massachusetts in October 1841, expressed profound anxiety when speaking to white audiences, attributing this discomfort to a long-standing reverence towards them borne out of his experiences as an enslaved person. He aimed to share the truth about slavery, affirming that while many abolitionists comprehended its history and horrors, they could not speak from the lived experience as he could. Douglass recounted brutal episodes of physical and psychological abuse that he and others had endured, describing the hypocrisy within the slaveholding community that used the Bible to condone the very oppression they inflicted, revealing a master who purported to be pious while committing unspeakable acts of violence. 1. He argued that a significant number of enslaved individuals recognized their inherent right to freedom, actively engaging in secret gatherings to share knowledge and uplifting narratives. He recalled how the words of abolitionists, like John Quincy Adams, resonated deeply among slaves, fueling their hopes for liberation. Douglass highlighted the vital role that the abolitionist movement played in stoking the flames of hope for enslaved individuals and spoke of the devastating impacts of family separations under slavery, stressing that the separation from loved ones created emotional trauma far worse than the physical beatings. 2. Douglass articulated a plea for emancipation, stating that it was the only resolution to the injustices of slavery, which would heal both the wounds of the enslaved and the social fabric of the Southern states. He compared the agony of physical punishment to the greater agony caused by the potential separation of families, emphasizing that the psychological pain endured by slaves due to the threat of being sold was insurmountable. 3. Transitioning from his reflections on slavery, Douglass confronted the pervasive prejudice he felt as a free man in the North, where the societal prejudices against Black individuals often proved as oppressive as the conditions of slavery. He recounted personal experiences of racial discrimination while traveling and searching for employment, asserting that attitudes against Black people were particular to the North, leading to a dehumanizing existence. 4. In his subsequent address in Hingham, Massachusetts, Douglass continued to shed light on the insidious nature of racism, recounting instances where he faced blatant discrimination from white passengers and establishments that refused him service. The church was also implicated, as he detailed moments when Black people were marginalized within religious spaces, illustrating a deeply ingrained cultural bias even among ostensibly pious community members. In a later correspondence to William Lloyd Garrison in 1842, Douglass described his activism efforts, detailing meetings he held that heightened awareness and compassion for the anti-slavery cause, bringing a moral reckoning to communities. He reflected on how the collective consciousness was awakened regarding the brutalities of slavery and expressed gratitude for the opportunity to speak out, despite health challenges that threatened his ability to continue publicly advocating for emancipation. 5. Douglass's journey took him beyond the United States, where he found himself in Ireland and Scotland. He was met with warmth and acceptance, contrasting starkly with his experiences in America. He shared his observations of the inherent racism that persisted even in supposedly more liberated spaces, emphasizing that the fight against slavery was a global struggle and called for solidarity from all quarters. His eloquent oratory transcended the racial barriers that often dictated interactions and rallied support for the abolitionist movement, reflecting his commitment to justice and humanity. Through Douglass's addresses and writings, he articulated a fierce testament to the horrors of slavery, the insidious nature of racism, and the critical need for social justice and collective action—inviting both moral and practical responses from individuals and nations to dismantle the systems of oppression that were entrenched in society.

Key Point: The Power of Truth through Shared Experience

Critical Interpretation: As you reflect on Frederick Douglass's profound acknowledgment of the significance of sharing lived experiences, consider how your own voice can become a catalyst for change. Just as Douglass, with all his courage, stood before those who held power and shed light on the brutal realities of slavery, you too can embrace the strength in vulnerability. No matter the context—be it your workplace, a community gathering, or an online platform—sharing your truth can inspire others to reflect, awaken compassion, and incite action. Just as Douglass's narrative not only educated his audience but also fortified the spirits of those he represented, your honesty about your struggles can forge understanding among diverse groups and unite people in their fight against injustice. Recognize the power you possess to influence the world around you, one honest conversation at a time.

Chapter 2 | Farewell to the British People: An Address

Frederick Douglass, in his farewell address to the British people on March 30, 1847, expressed both gratitude and disillusionment regarding the systemic injustices of slavery in America. He began by humbly acknowledging that he did not possess great oratory skills, yet he carried the voice of the oppressed with him. His intent was to speak truthfully about the plight of enslaved individuals in the United States and to garner support for the abolitionist movement. 1. The Hypocrisy of American Institutions: Douglass critiqued the foundational ideals of the United States, highlighting the contradiction between the nation's professed beliefs in liberty and the grim reality of slavery. This pointed hypocrisy, he asserted, made Americans morally bankrupt. He underscored that the same statesmen who drafted the Declaration of Independence were also complicit in the enslavement of fellow human beings, branding the entire system as a great falsehood wrapped in euphemisms that masked the brutal truth of slavery. 2. Constitutional Protections for Slavery: Douglass analyzed specific clauses in the American Constitution that upheld slavery, portraying how legal language enshrined the oppression of black individuals. He explained that the Constitution turned every white American into an ally of the slave system, legitimizing the hunting down of fugitives and assuring that freedom was relegated solely to the white populace. This vested interest in maintaining the status quo encouraged a culture of violence and repression against black people, as even those attempting to escape enslavement risked severe punishment. 3. Moral Argument Against Slavery: Douglass articulated that the moral fabric of America was stained by slavery. He noted the deep theological hypocrisy whereby Christian institutions and leaders preached about love and freedom while perpetuating a system that treated human beings as property. This created an environment where abolitionists, those fighting against such moral decay, were often branded as radicals or even infidels. His determination was not just to reveal the truth about slavery but to highlight the dire need for a moral reckoning. 4. Call to Action: Douglass energized his audience by emphasizing the need for continued agitation against slavery. He linked the struggle for freedom to universal human rights, asserting that the fight against slavery was not merely an American issue but a concern that reverberated globally. He implored the British audience to remain vigilant and outspoken against American injustices, emphasizing that their outspokenness had the potential to instigate change. 5. Personal Experience and Witness: Douglass shared anecdotes from his own life to personalize his message. With palpable emotion, he recounted the indignities faced by black individuals in America—from humiliation in public spaces to systemic exclusion. His experience in England was starkly different; he recognized the kindness and respect shown to him, which reinforced his belief in the fundamental human rights owed to everyone irrespective of skin color. 6. Acknowledgment of Allies: Douglass acknowledged the support of individuals and groups, particularly those in England, who fought alongside him and championed his cause. He expressed deep appreciation for the camaraderie and advocacy shown to him while he traveled through Britain. This connection reinforced his resolve to return to America with the burden of the enslaved on his heart and to continue the fight for their freedom. 7. Return to America: With a firm commitment, Douglass declared his intention to return to the United States to fight for the emancipation of enslaved individuals. His desire for freedom was not merely for himself but for all oppressed people, revealing his profound sense of responsibility towards his community. His concluding sentiments underscored a promise to honor the struggles of his fellow Africans by relentlessly pushing against the structures of oppression. In essence, Douglass’s farewell address encapsulated a powerful call for awareness and action against the cruelties of slavery, urging collective responsibility to strive for a true realization of liberty and justice for all.

Chapter 3 | To the National Anti-Slavery Standard

In September 1847, Frederick Douglass wrote to the National Anti-Slavery Standard, expressing the palpable enthusiasm surrounding the anti-slavery movement in the West. He reported that a significant revival was occurring, with unprecedented crowds gathering to support this noble cause. Douglass emphasized how the power of pro-slavery forces was shaken, as even religious institutions, which had sanctioned slavery, faced growing discontent from the people. Douglass expressed hope that with adequate resources, the laws discriminating against free Black individuals in Ohio could be repealed swiftly. However, he lamented the limited number of advocates in this vast and ready region for anti-slavery efforts. During the anniversary of the Western Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass described a particularly remarkable event characterized by the presence of passionate speakers and musical performances that deeply moved a crowd of around four thousand. He highlighted the newly invigorated involvement of local women in anti-slavery fairs, reflecting an evolving dynamic in their engagement with the movement. On December 3, 1847, Douglass utilized his platform in the North Star to rededicate it to the struggles of oppressed individuals. He made a passionate case for asserting their rights and demanding justice, condemning both Southern and Northern complicity with slavery. Douglass called for a united front against tyranny, emphasizing a commitment to both the rights of the oppressed and their responsibilities. Douglass also addressed the war with Mexico, proclaiming it a disgraceful exercise of power driven by greed and imperial ambition. He criticized leaders who justified the war under the guise of honor and national interests while expressing deep concern over the moral decay this conflict bred within the nation. In a speech entitled "The Slaves’ Right to Revolt," Douglass boldly confronted those who continued to uphold the institution of slavery. He insisted that assertions of bravery were hypocritical from those who benefited from slavery's oppression. He invoked the history of resistance among enslaved individuals, calling for solidarity as he implored Northern supporters to cease their complicity with slaveholders. Douglass dedicated an op-ed to women’s rights in late July 1848, affirming his belief in gender equality and the urgent need for women's political rights. This advocacy was echoed in the context of the Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention, where women firmly asserted their grievances and rights. In a letter to Thomas Auld on September 3, 1848, he utilized the occasion of his emancipation anniversary to reflect on his experiences, boldly expressing his journey from slavery to freedom and his desire to know the fate of family members left behind. Douglass's poignant recollections highlighted the brutality of slavery juxtaposed with the personal triumphs of self-emancipation and family relationships. Addressing a gathering in honor of Robert Burns, Douglass expressed admiration for Scottish character and declared pride in his connection to the themes of freedom and human rights present in Burns' work. Later, he tackled the contentious issue of colonization, arguing against the notion of exporting free Black people from America to Liberia, asserting, "We are here; and here we shall remain." He asserted that their labor and culture were integral to America, thus reinforcing their right to stay. In March 1849, Douglass published an article critiquing the U.S. Constitution, asserting that, while it might not seem inherently pro-slavery when read in isolation, it was fundamentally a document shaped by the interests of slaveholders. He argued that analyzing the Constitution in its historical and social context revealed its complicity in maintaining slavery and injustice, thus calling for its overthrow. Lastly, in a consideration of the future of Black Americans in November 1849, Douglass articulated a resilient connection to the land, asserting that the destiny of both Black and white Americans were interwoven. He denounced the continued existence of slavery as detrimental to the nation as a whole, urging a reevaluation of political policies toward Black citizens, advocating for equal rights and opportunities as essential for the nation's moral and economic wellbeing. Through Douglass’s impassioned words, he not only chronicled the struggle against slavery but also laid the groundwork for broader social reforms that would transcend race and gender.

Chapter 4 | Weekly Review of Congress

The essence of the selected texts reflects Frederick Douglass's passionate critique of slavery and its implications on American society, politics, and morality during the 19th century. His words encapsulate both the brutality of slavery and the deep hypocrisy inherent in a nation that professes freedom while subjugating millions. Below is a rich summary that captures the core arguments without overt headings, ensuring a smooth narrative flow. 1. Douglass asserts that while major speeches in Congress may provide comprehensive views on slavery, they often fail to address the fundamental moral crisis it represents. He calls out prominent figures like John C. Calhoun and Daniel Webster for their flawed arguments, illustrating Calhoun's disillusionment with the anti-slavery movement and Webster's betrayal of the very principles of freedom he claims to uphold. These speeches reveal a broader societal struggle over the issues of slavery and liberty, demonstrating that even the most eloquent defenders of slavery cannot provide substantial justification for its continuation. 2. Reflecting on the palpable tension resulting from the Fugitive Slave Law, Douglass highlights the fear and dislocation experienced by many free blacks who feel vulnerable to being captured and returned to slavery. He describes the emotional turmoil of fugitives who have escaped bondage only to face the threat of being hunted down. This context underscores the psychological impact of slavery on both those who are enslaved and those who attempt to live freely. 3. The stark contrast between the ideals of independence celebrated on events like the Fourth of July and the lived experiences of slaves is a recurring theme in Douglass's rhetoric. He poignantly articulates how the very freedoms enjoyed by white Americans serve as a cruel reminder of the ongoing subjugation of black individuals. The holiday symbolizes national pride but simultaneously exposes the deep injustices faced by the enslaved who are denied the rights to liberty and equality. 4. Douglass's discourse also critically examines the role of religious institutions and the moral contradictions they embody. He denounces churches that remain complacent or even supportive of slavery, arguing that their inaction undermines their moral authority. The complicity of religious leaders in perpetuating the system of slavery reflects a broader hypocrisy that Douglass vehemently condemns. 5. Throughout his oratory, Douglass acknowledges that the road to abolition is fraught with challenges but insists on the eventual triumph of liberty and justice. He draws inspiration from the actions of past abolitionists and expresses hope for a future where the humanity of all individuals is recognized and upheld. His assertions reflect an unwavering faith that the principles of justice and equality will ultimately prevail over the institution of slavery. 6. Lastly, Douglass highlights the insidiousness of the internal slave trade within the United States, using vivid imagery to convey the inhumane treatment of enslaved people. He illustrates the brutal realities of the human auction block and the emotional devastation visited upon families separated by the slave trade. In doing so, he reinforces the idea that slavery is not merely an economic institution but a profound moral failure that shames the nation. In conclusion, Douglass’ speeches and writings serve as a powerful indictment of slavery, challenging his audience to confront their complicity and urging them towards a collective moral awakening. His vision speaks to a future where all men and women can claim their rightful place in society, liberated from the chains of oppression. His eloquence and conviction illuminate the path toward justice and equality, emphasizing the necessity of perseverance in the face of tyranny. Douglass's timeless call to action resonates even in contemporary discourses surrounding race, justice, and human rights.

Chapter 5 | Our Position in the Present Presidential Canvass

Frederick Douglass, in his writings from the early 1850s, passionately addresses the issues of slavery, racial equality, and the moral obligations of both individuals and society as they pertain to these critical matters. 1. Support for the Free Democratic Party: Douglass openly declares his alignment with the Free Democratic Party's presidential candidates, intending to galvanize support to fight against slavery. He reassures his commitment to push for a government that embodies moral righteousness, emphasizing that supporting anti-slavery candidates is essential to achieving liberty and justice. 2. The Primacy of Slavery as an Evil: Douglass unequivocally states that slavery is the greatest evil afflicting the United States. He argues that it degrades not only the enslaved but also the morals and ethics of the entire nation, making true liberty unattainable. The urgency of abolishing slavery is underscored, with Douglass asserting that until this foundational issue is resolved, the country cannot progress. 3. Moral Responsibility of Voters: He addresses the moral dilemmas faced by voting abolitionists, urging them to translate their moral beliefs into political action. Douglass articulates a philosophy of political engagement where a vote must strive to achieve the highest possible good, rather than aiming for an unattainable perfection. He critiques those who refuse to vote for candidates that do not align perfectly with their views and encourages pragmatic alliances for the sake of the abolition movement. 4. Unity of Purpose: Douglass stresses the importance of unity among factions opposing slavery. He highlights that a unified front can wield more power than fragmented groups. The strength lies in a collective effort against the pervasive institution of slavery, which undermines all other reforms and moral advancements. 5. Critique of Compromises with Slavery: He critiques historical compromises that perpetuate the existence of slavery, arguing that they only serve to perpetuate moral decay and the normalization of injustice. Douglass calls for a complete rejection of any political agreements that do not support the immediate abolition of slavery and advocates for confronting the slave system head-on. 6. The Viability of Abolition: Douglass expresses faith that slavery can and will be abolished, emphasizing that the moral arc of the universe is inclined toward justice. He encourages individuals to confront the harsh realities of slavery with courage and integrity, pointing out that the moral nature of society is tied to how it treats its most vulnerable members. 7. Economic Power and Self-Sufficiency: Douglass underscores the critical necessity for free Black individuals to acquire trades and skills to secure their livelihoods. He articulates a clear message: the only way to ensure dignity and opportunity is through self-reliance and economic empowerment, arguing that education and trade skills are vital components of self-advancement in a society that continues to marginalize them. 8. The Role of Women and Ministers: Throughout his speeches, Douglass acknowledges the roles of women and women-led movements in advancing the cause against slavery. He recognizes their capacity for mentorship and advocacy in uplifting the marginalized community, reinforcing interconnectedness in social justice efforts. 9. Abolitionism as a Catalyst for Change: Douglass emphasizes the broader implications of abolitionism—not as an isolated movement but as a vital catalyst for human rights advancement. He contends that the fight against slavery is intrinsically linked to the fight for civil rights, gender equality, and numerous social reforms. 10. Moral and Ethical Considerations: Douglass advocates for a rigorous ethical framework guiding actions against slavery. He argues that true justice is not only a legal matter but a sacred moral obligation. He challenges the ethos that human life must be preserved at any cost, suggesting that there may be righteous causes warranting self-defense, particularly in the context of a violent and oppressive system. Through this multifaceted discourse, Douglass calls upon the collective moral sensibilities of his audience to act decisively against the institution of slavery, promote unity among abolitionists, and empower the Black community towards self-sufficiency and rights in the face of entrenched systemic racism. His work serves as a timeless plea for justice, activism, and moral integrity in overcoming societal injustices.

Chapter 6 | Slavery, Freedom, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act: An Address

In this powerful address delivered on October 30, 1854, Frederick Douglass speaks to a gathering in Chicago about the pressing national issue of slavery and its profound implications for American society. His speech begins with an acknowledgment of the painful reality that many still view him as an intruder in discussions about civil rights. He calls upon the audience to recognize his constitutional and natural right to participate in this critical dialogue—emphasizing that the principles of American democracy should not exclude people of color. 1. The struggle for recognition: Douglass asserts his identity as an American citizen, drawing on the foundational principles of the Constitution to argue against any notion that undermines his rights or the rights of African Americans. He insists that his fight is not solely personal but tied to the broader struggle for the freedom of all enslaved individuals. He highlights the urgency of the moment, reinforcing that the fight against slavery transcends party lines and is a matter of human rights. 2. The truths of slavery and freedom: He articulates the incompatibility of liberty and slavery, stating that truly free institutions cannot coexist alongside the institution of slavery. Douglass critiques the political leadership of the time for their complicity with slavery, insisting that the South must choose between giving up slavery or forcing the North to relinquish its liberties. He warns that the institution of slavery inherently opposes progress and freedom. 3. The unjust nature of politics: Douglass criticizes the political parties of the era, pointing out that both the Democratic and Whig parties have compromised the cause of abolition for the sake of political expediency, abandoning their moral obligation. He condemns the Kansas-Nebraska Act as a betrayal of the principles Americans professed to uphold while emphasizing the need for integrity and authenticity in the anti-slavery movement. 4. A call to arms for moral action: Douglass urges active resistance against the Slave Power, asserting that the fight for civil rights must be unyielding and fervent. He warns that mere opposition to slavery without tangible actions to end it serves only to embolden oppressors. He reiterates that the only legitimate struggle is the complete abolition of slavery, free from compromises that undermine the dignity and rights of enslaved individuals. 5. The outlook for ultimate victory: In his closing remarks, Douglass expresses optimism about the anti-slavery movement's potential for success. He argues that, although the immediate future may appear daunting with the power of slaveholders entrenched, the moral arc of history bends towards justice. He encourages his audience to unite in the cause for liberty and justice, confident that the principles of freedom and equality will prevail in America. Through a blend of personal testimony, political analysis, and a profound moral appeal, Douglass's address serves not only as a condemnation of slavery but also as a rallying cry for collective action towards achieving true freedom for all Americans. His fierce commitment to justice underscores the long-standing struggle for civil rights, echoing through history as an enduring call to action against oppression.

Key Point: Your identity and rights as a human being are unassailable.

Critical Interpretation: Douglass’ assertion of his rightful place as a participant in discussions on civil rights serves as a powerful reminder to you that no matter your background, your voice matters. This chapter inspires you to embrace your identity fully and engage actively in conversations about justice and equality. In a society where voices can often be marginalized, Douglass' courage to claim his space compels you to stand up and assert your own rights and the rights of others, challenging injustices and advocating for change. By recognizing the importance of your unique perspective, you not only honor Douglass’ legacy but also contribute to the ongoing fight for freedom and equality, understanding that every effort counts in the pursuit of justice.

Chapter 7 | Progress of Slavery

In Chapter 7 of "The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass," Frederick Douglass reflects on the evolving landscape of slavery in America, the progress of the anti-slavery movement, and the political dynamics that shape it. His examination presents both a historical overview and a fervent rallying cry for continued activism against the institution of slavery. 1. Douglass begins by acknowledging the optimism often found among abolitionists regarding the growth of anti-slavery sentiments in the United States. He emphasizes that reformers thrive on tangible evidence of progress, even if such evidence can sometimes be misleading. Acknowledging this human tendency, he nevertheless argues that true faith in liberty grants reformers clarity and strength, allowing them to perceive the ultimate defeat of oppression despite the present challenges. 2. The narrative contrasts the initial fervor of the anti-slavery movement, which faced violent opposition, with the current state of complacency among slaveholders, notably represented by Georgia politician Mr. Stephens. Douglass highlights that slaveholders now view slavery as a fixed and entrenched institution rather than a temporary evil. This shift in perspective reveals a significant regression in moral and ethical consideration toward slavery, as public figures now espouse its supposed benefits rather than its inherent moral failures. 3. Douglass critiques the profound disconnect between the internal logic of slavery and the principles laid out in the Constitution. He argues that the Constitution's framers did not intend to sanction slavery. Instead, they imagined a nation founded on liberty and justice, even though practice diverged significantly from these ideals. He advocates for a reading of the Constitution that interprets it in a way that supports freedom rather than oppression, insisting that any interpretation that supports slavery undermines the foundational purpose of the government. 4. In addressing the complexities of social politics, Douglass critiques the positions some abolitionists take—that the Constitution is irrevocably pro-slavery. He rebukes this stance, insisting that the Constitution must be viewed in light of its overarching goals of liberty and justice. He distinguishes between the bad practices of public officials and the ideals articulated in the Constitution, asserting that the Constitution itself is a document of liberation, which has been perverted by human greed and systemic oppression. 5. Douglass emphasizes the critical need for action both through political engagement (the "ballot") and moral imperative (the "bullet"), though he expresses skepticism about relying on violence. He maintains that effective advocacy for abolition requires a synchronized effort for both moral persuasion and political action to create substantial change. 6. Ultimately, Douglass's writings serve as both a critique of contemporary attitudes toward slavery and a call to action. His insistence on recognizing African Americans as full members of society, deserving of rights and dignity, stands at the heart of his arguments. He urges his readers to reject complacency and engage vigorously in the fight for freedom. Through this chapter, Douglass deftly navigates the themes of progress, the moral nature of slavery, the need for active engagement in political processes, and the ongoing struggle for emancipation, laying out a vision for a more just society that actively upholds the principles of liberty and human dignity.

Chapter 8 | The Late Election

In the wake of the election of Abraham Lincoln as President, the political landscape of the United States underwent significant transformation, particularly regarding the contentious issue of slavery. Douglass begins by asserting that the election heralds a new order of events, with profound implications for the Southern slave system, bringing to light the stark contrasts between Lincoln and his opponent, the Southern candidate Breckinridge. The latter firmly represented the unabashed assertion that property rights extend to slaves, while Lincoln's stance is characterized by a more restrained view that recognizes slavery as an existing, localized evil not to be extended. Simultaneously, the Southern agitation against "Northern aggression" reveals the depth of their fears surrounding the election of a President who opposes the spread of slavery. Southern leaders rally, speaking of secession and a Southern Confederacy—a reaction stemming from the mere prospect of a President who symbolizes a shift against their entrenched beliefs. Douglass expresses confidence that these reactions are based on unfounded fears; no genuine threat exists to slavery under Lincoln, who is likely to act as a protector of the institution in its current states. Douglass further posits that Lincoln’s election diminishes the Southern oligarchy's long-standing power, showcasing Northern resolve to reclaim authority lost to Southern influence. This election marks possibilities that were once thought beyond reach—the prospect of electing anti-slavery representatives to the presidency and demonstrating the Northern population's willingness to confront the indominable grip of slavery. The discourse shifts to the implications of maintaining the union alongside the existence of slavery, where a Republican administration may not represent a radical shift towards abolition. Douglass voices concerns that the Republican party, desiring to mitigate tensions rather than confront the systemic issues of slavery head-on, risks stifling abolitionist movements. Notably, he emphasizes the need for active opposition and calls for renewed efforts towards complete and universal abolition. As Douglass shares his insights during the tumultuous political climate of the time, he touches upon the necessity of various methods for battling slavery, including moral, political, and even revolutionary measures—all methods that resonate with the legacy of figures like John Brown, who undertook drastic actions in pursuit of freedom. Douglass’s call to action is rooted in the belief that mere political pandering to slave interests is insufficient; true liberation demands engagement and a commitment to visibly confront the institution of slavery. Turning to the scope of the war precipitated by slavery, Douglass articulates a clear stance: the war must be waged not just to preserve the Union but to abolish slavery, which he asserts is the war’s primal cause. The repercussions of a war fought without the intent to address slavery would ultimately lead to a peace that perpetuates suffering rather than remedies it. He argues for the incorporation of free and enslaved black people into the military as a liberating force. The speech reaches its pinnacle as Douglass advocates for the liberation of all slaves within the rebel states, urging that the opportunity for a decisive end to slavery coincides with the burgeoning conflict. He contends that no faction opposing slavery should falter in their resolve to eradicate it, positioning this moment in history as one of profound potential for justice. In a broader reflection on American identity, Douglass highlights the moral failure of the nation should it choose to uphold a government that accommodates slavery. Pointing to the deep-rooted contradictions within American society, particularly around concepts of freedom and justice, he stresses that the future security and integrity of the nation hinges upon its ability to confront this fundamental injustice and dismantle the system that enables it. Throughout his address, Douglass fortifies his view that the path to true liberation necessitates not only the rejection of slavery but a renewed commitment to fully realize the principles of equity and justice, thereby reclaiming the dignity and humanity of every individual. His call serves as both a testament to the ongoing struggle for emancipation and an urgent appeal for all Americans to take decisive steps toward a society free from the blights of oppression and inhumanity.

Chapter 9 | Fighting Rebels with Only One Hand

Frederick Douglass, in his writings throughout 1861 and 1862, passionately addresses the moral, political, and social crises that plagued the United States during the Civil War, particularly as they pertained to slavery and the exclusion of African Americans from the fight for freedom. His eloquent arguments can be summarized as follows: 1. Urgency of Action Against Slavery: Douglass criticizes the reluctance of the American government to enlist Black men in the Union Army despite their vested interest in the defeat of rebel forces. He asserts that the refusal to acknowledge the potential of African Americans in battle stems from deep-seated prejudice and cowardice. The nation’s leaders demand men while neglecting a crucial demographic eager to defend freedom, illustrating a tragic oversight during a moment of dire need. 2. Strategic Missteps of the Government: Douglass laments that the government, in its attempts to maintain peace and appease pro-slavery sentiments, suffers from moral blindness. He decries the complicity of the Union in upholding slavery, arguing that true national preservation cannot occur while slavery persists. He insists that only through embracing justice and the rights of all men can the Union hope to rally its strength against the rebellion. 3. Critique of Confederate Motivations: Douglass points out that the rebellion is fundamentally rooted in the desire to uphold slavery. He notes that Confederate forces employ Black laborers, thereby highlighting the hypocrisy of a system that both exploits and denigrates African Americans. Douglass argues that true progress toward emancipation will not come from appeasement but rather from a decisive stance against the institution of slavery. 4. Call for Emancipation: He underscores that the abolition of slavery must be seen as essential to national survival. Douglass calls for a more aggressive approach, including emancipation proclamations from the President, to weaken the rebellion's core. The abolition of slavery is portrayed as the only solution to secure lasting peace and unity in the nation. 5. Identity of African Americans: Douglass advocates for the recognition of African Americans as equal citizens deserving of rights and opportunities. He refutes claims about the supposed incapability of freed Black individuals to care for themselves or contribute to society. Instead, he implores that given a fair chance, they have shown resilience and the ability to thrive. 6. Historical Context of Oppression: Douglass draws parallels between the history of slavery and other oppressive systems, arguing that the fate of the African American community should not be viewed as a threat to societal stability but rather as an essential aspect of humanity’s moral evolution. He asserts that the true measure of a society's greatness lies in its treatment of its most vulnerable. 7. Criticism of Military Leadership: In his assessments of Union generals such as McClellan, Douglass is critical of leadership that remains passive or complicit in the face of rebellion. He raises concerns over a lack of urgency and commitment in fully engaging with the rebellion, maintaining that victory cannot be achieved while adhering to outdated prejudices against African Americans. 8. Vision for the Future: Douglass concludes with a clarion call for complete abolition and transformation. He envisions a society where justice and liberty are conjoined, echoing the sentiments of the fathers of American independence. He emphasizes that a decision to maintain slavery will only lead to further bloodshed and moral decay. The path forward requires embracing emancipation not just as a necessity but as a moral obligation for true national identity and integrity. Through these compelling arguments, Douglass advocates for the inclusion of Black Americans in the struggle for freedom, articulates the dangers of complacency regarding slavery, and insists that without embracing justice, the nation's future is at grave risk. His eloquence serves as both a historical witness and a moral guide, urging the American people to uphold the values of freedom, equality, and justice for all.

Chapter 10 | The Spirit of Colonization

In "The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass," Chapter 10 encompasses key themes regarding the fight against colonization, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the role of African Americans in shaping their destiny. Through Douglass' passionate discourse, we are offered a deep understanding of the complexities surrounding race relations and the struggle for freedom in America during the Civil War era. 1. The insidious nature of colonization is sharply critiqued. Douglass argues that the Colonization Herald and its proponents perpetuate a malevolent agenda cloaked in religious sanctity, masking their intentions to remove free Black individuals from the United States rather than addressing the prejudice they face. The connection between colonization and the violent mobs targeting free Black people in various Northern cities demonstrates a disturbing collaboration between ideologies of racial superiority and the violent enforcement of such beliefs. 2. Douglass challenges the colonization argument that the Black race is incapable of integration into American society. He refutes assertions that centuries of servitude taint the Black character, positing instead that the true evil is rooted in the systemic racism and slavery that undermine the potential for social harmony. He highlights that people of all races can coexist peacefully—what is needed is societal will, nurtured by justice and equality. 3. The critical moment of January 1, 1863, looms large in Douglass’ reflections, portraying it as a crossroads for America. He heralds President Lincoln's forthcoming Emancipation Proclamation as crucial for both Black liberation and national integrity, emphasizing that failure to issue it would be a grievous betrayal to the soldiers who have fought against oppression. Douglass calls for unity among all who seek freedom, underscoring the notion that the fight for emancipation benefits not just the enslaved, but society as a whole. 4. There is a clarion call for action among African Americans, whose potential for military service is underscored. Douglass argues that the integration of Black troops into the Union Army is not merely a tactical necessity; it is a moral imperative. Black men’s willingness to fight for their country must be recognized and harnessed, for they yearn for the opportunity to defend their and the nation’s freedom. 5. The future, according to Douglass, hinges on a transformation of Southern society post-Emancipation, marking a critical juncture that requires both courage and enlightened governance. The task of reconstructing society must acknowledge the newly freed individuals and foster conditions for their flourishing. He rejects the notion that freedom can be achieved without profound changes in social attitudes and governmental policies. 6. Douglass asserts that the advocacy against slavery must persist beyond mere political maneuvers. There is a critical need for societal change that encompasses education, equality before the law, and the dismantling of prejudices that have long diminished the value of Black lives. The progress towards achieving true freedom and equality is a labor that follows the abolition of slavery. 7. The chapter culminates with an urgent plea for solidarity—a call for both Black and white Americans to unite in the cause of justice and emancipation. Douglass’ vision emphasizes the weight of collective responsibility in achieving lasting change and underscores his unwavering faith in the potential for progress forged through struggle and resilience. In essence, Douglass' powerful arguments outline a profound understanding of the interplay between race, freedom, and societal structure in America. He champions the dignity and capabilities of African Americans, urging both them and their allies to seize the moment of impending change to carve a true path towards liberty and equality.

Key Point: The Importance of Collective Solidarity in the Fight for Justice

Critical Interpretation: Douglass’ fervent call for unity between Black and white Americans teaches us that achieving meaningful change requires coming together across divides. In your own life, consider how collaboration and shared purpose with diverse communities can amplify your impact. Whether it’s in advocating for social justice, environmental causes, or community development, remember that your voice is stronger when joined with others. Engage actively, listen to different perspectives, and build alliances that foster empowerment and understanding. Just as Douglass believed that collective action is essential for freedom, you too can inspire change by recognizing the importance of teamwork and solidarity in your pursuits.

Chapter 11 | Men of Color, To Arms!

In this poignant segment of Frederick Douglass's writings, he calls upon men of color to take up arms for their freedom and the liberation of their enslaved brethren amid the Civil War. Douglass, writing in March 1863, passionately argues that the conflict is not merely a "white man's war," but a fight for the very liberty of the African American community. This assertion is grounded in his belief that the might of the enslaved can be a potent force against their oppressors, and he urges his fellow men not to hesitate but to enlist in the military and join the ranks of those already fighting valiantly on the front lines. 1. Douglass emphasizes that the necessity of colored men joining the struggle is long overdue, framing it as a moral imperative. He urges that inaction in the face of injustice is disgraceful, advocating instead for courageous action that can lead to both personal and collective liberation. 2. The call to arms is bolstered by a notable appeal to shared humanity and citizenship. Douglass reminds his audience that they are not only men but also American citizens, deserving of the same rights and recognition as all others. He implores them to seize the opportunity afforded by the ongoing war to create a brighter future for themselves and their descendants. 3. He draws attention to the enemy's disdain for armed whites fighting alongside black soldiers, asserting that true emancipation will not come from passivity but through bold and unified efforts against the hate embodied in the Confederate rebellion. 4. Douglass pays tribute to the sacrifices of earlier freedom fighters such as Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner, framing their actions as profound examples of resistance. He believes that history will judge those who fought for liberty favorably, and that embracing this struggle can redeem the black community's honor in the eyes of the nation. 5. The establishment of black regiments, specifically mentioning the 54th Massachusetts, represents a watershed moment in which men of color are not only considered integral to the effort but recognized equally with white soldiers in terms of rights, pay, and respect. 6. Douglass's treatise extends beyond military service; he sets forth the idea that engagement in the army offers black men the practical knowledge and skills to secure their rights in the future, highlighting the long-term benefits of their involvement in the war. 7. Through the course of his writings, Douglass identifies the systemic injustices of slavery and their repercussions on societal attitudes toward black people. He challenges the notions that black men are inherently inferior or incapable, framing their enlistment not merely as a matter of self-defense but as an act of self-assertion—an escape from the shackles of oppression. 8. Douglass advocates for immediate claims to citizenship and voting rights for black men, asserting that the right to vote is not only a fundamental human right but also an essential step toward equality and respect within American society. 9. Finally, Douglass conveys a sense of urgency and necessity in the fight against slavery, underscoring that the outcome of the war will not only determine the future of the nation but will also decide the fates of millions still in bondage. Thus, he insists that the fight must continue until complete abolition and equal rights are achieved. In closing, Douglass expresses his profound gratitude to the readers of his publication for their consistent support over the years. He reflects on the pivotal role that African Americans must play in shaping a future free from the encumbrances of racism and systemic oppression, ultimately urging them to heed the call of history and stand united in their fight for freedom.

Key Point: Embrace Courageous Action Against Injustice

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing in the shoes of Frederick Douglass, feeling the weight of history on your shoulders as he calls upon you to join the fight for freedom. His words resonate deep within, igniting a fire that compels you to not just be a bystander in life but to actively engage with the injustices around you. Douglass emphasizes that remaining silent in the face of oppression is a disgrace—this rallying cry urges you to recognize the moral imperative to advocate for what is right. You are struck by the realization that true liberation comes from taking bold and courageous actions, not from waiting for change to happen on its own. Inspired by Douglass’s courage, you feel empowered to stand up against injustices in your own life, whether big or small, and to fight not just for your own rights but for the rights of those who are marginalized. Every act of bravery contributes to a collective movement towards justice, filling your life with purpose and instilling a belief that by joining together, you can reshape the world into one where freedom and equality prevail.

Chapter 12 | Our Composite Nationality: An Address

In his address "Our Composite Nationality," delivered on December 7, 1869, Frederick Douglass provides a thoughtful exploration of the character and mission of the United States, emphasizing the importance of its diverse population and the necessity of equality among all races. His reflection can be outlined through key themes that encapsulate his thoughts on national identity, race, and the future of America. 1. Significance of National Organization: Douglass opens by detailing the importance of nations as fundamental human constructs that signify a transition from chaos to structured society. He emphasizes that the composition of the United States is exceptional, marked by its amalgamation of varied races, each contributing uniquely to the fabric of national identity. This diversity is seen as a strength, proposing that such an organization offers a pathway to enlightenment and progress. 2. American Exceptionalism: Douglass argues that while other nations have peaked, the United States stands at the brink of its potential greatness. He perceives the U.S. as possessing vast resources and potential for growth, suggesting that the vitality of a nation lies in its ability to evolve and adapt to expanding responsibilities and rights. He believes that the nation is not only fortunate but also at the dawn of unprecedented opportunities. 3. Critique of Pessimism: Addressing the pessimists who contend that America has seen its better days, Douglass challenges this notion by demonstrating how history is punctuated by periods of uncertainty that often precede growth. He identifies a consistent thread of trepidation that accompanies significant change, yet reiterates that many dire predictions made in the past have ultimately been proven false. This inspires a call to action, fostering hope rather than despair. 4. Political Philosophies and Governance: Central to Douglass's philosophy is the idea of governance rooted in justice and equality. He advocates for a government sanctioned by and accountable to the will of the people, free from the biases of race or creed. By positioning American governance against the backdrop of European models of discrimination and hierarchy, he aims to underline the moral imperative for equality as a foundational principle. 5. Racial Equality as a Historical Necessity: Douglass urges that the future of the United States relies on embracing its multicultural essence and endorsing absolute equality among all races. He emphasizes that as a nation comprised of diverse ethnicities, the U.S. must address the grievances of marginalized groups, particularly African Americans and Native Americans, establishing a cohesive national identity that transcends race. 6. The Challenge of Immigration: Douglass acknowledges the ongoing influx of immigrants, notably from China, and points out that this new demographic could influence America's societal structure. He asserts that immigration should be welcomed as a natural extension of America's identity, arguing that diverse populations can enrich society and contribute significantly to national progress. 7. Human Rights and Social Justice: A recurrent theme in Douglass's dialogue is the assertion that the rights of humanity ought to supersede those of national interest. He envisions a society where social justice expands to include all people, reinforcing the idea that universal rights grant everyone an equal opportunity for freedom and prosperity. 8. Conditions for Progress: Douglass emphasizes that while various races may present distinct cultural attributes, all possess the potential for improvement. He insists on welcoming individuals from every background, believing that collective aspirations and knowledge enhance national unity. The interconnection among different races is posited as crucial to the broader human experience to achieve greater social harmony. Douglass concludes his address with a poignant acknowledgment of the collective struggle for liberty that each race has endured and the ongoing need to champion the rights of all people. His powerful rhetoric reaffirms the resilience and aspirations of marginalized populations, advocating an inclusive future that embodies the democratic ideals of the nation. The overarching message is clear: the strength of the United States lies in its ability to embrace and celebrate its diversity, fostering a sense of belonging and equality for all its citizens.

Chapter 13 | Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln: An Address

In Chapter 13 of "The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass," we find a profound oration delivered by Frederick Douglass in memory of Abraham Lincoln, showcasing the remarkable journey from bondage to freedom and reflecting on historical progress. This address unfolds as Douglass marvels at the present circumstances that allow for such gatherings, emphasizing the powerful change in societal attitudes towards race since the era of slavery. Douglass articulates several key points throughout his oration, spanning the acknowledgment of Lincoln's contributions to freedom, the challenges faced by freed individuals, and the ongoing quest for equality. 1. Douglass begins by celebrating the momentous occasion of the assembly, noting how the participants can now honor Lincoln openly and peacefully, a stark contrast to the violent suppression that would have characterized similar gatherings twenty years prior. This peaceful assembly hints at the progress achieved in the nation, offering hope for an enlightened future where the losses and evils of the past are no longer tolerated. 2. Douglass draws a clear distinction between the past conditions of enslavement and the current era of freedom. He reflects on the fruits of emancipation, including the ability of formerly enslaved individuals to gather and honor Lincoln – the man who played a critical role in their liberation. He emphasizes that this occasion serves as a testament to both the sacrifices of the past and the possibility of a united future. 3. At the heart of Douglass's speech lies a nuanced understanding of Lincoln's legacy. He acknowledges Lincoln’s essential role in emancipation while highlighting the reality that Lincoln primarily represented the interests of white Americans. This juxtaposition reveals Douglass's deep appreciation for Lincoln while also asserting that true equality and justice require deeper reckoning with the realities of race in America. 4. Douglass firmly believes that Lincoln’s administration, despite its compromises with slavery, advanced the cause of freedom. Specifically, he recalls the moments of struggle during the Civil War when faith in Lincoln’s leadership brought hope to black Americans. Through a series of historical references, he illustrates how Lincoln’s actions, such as issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, ignited a collective struggle for freedom and human rights. 5. As the address unfolds, Douglass provides a candid reflection on the burdens placed on newly freed individuals in a society still grappling with the remnants of racism and discrimination. He passionately asserts that while Lincoln’s legacy must be honored, the commitment to secure equal rights for all must remain an essential focus for the future. 6. Douglass captures the enduring spirit of hope among the formerly enslaved, expressing a vision united with Lincoln’s principles. He encourages the audience to recognize that the memory of their struggles and achievements binds them to Lincoln’s legacy—a legacy that, despite its imperfections, laid the groundwork for a society striving for liberty and equality. 7. He also emphasizes the importance of gratitude towards Lincoln, while reminding all citizens of the unresolved issues that linger post-emancipation. By advocating for continued action against injustice, Douglass insists that the black community's progress must be asserted boldly and recognized universally. 8. In conclusion, Douglass implores his audience to remember that their struggles are intertwined with America’s broader narrative. He frames the dedication of the monument to Lincoln not merely as an honoring of a presidential figure, but as a collective commitment to achieving a future marked by equity and justice for all, regardless of race. Through this oration, Douglass encapsulates the intricate tapestry of American history that binds the pursuit of freedom with the ongoing challenges against inequality, urging future generations to uphold Lincoln’s vision while striving to realize its fullest potential. His eloquent delivery serves as both a reflection on past injustices and a bold call to action for ongoing dialogue and progress toward true equality.

Chapter 14 | The Color Line

In Chapter 14 of "The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass," titled "The Color Line," Frederick Douglass grapples with the persistent issue of racial prejudice, arguing that it is an ingrained moral disorder that society perpetuates through irrational beliefs and systemic injustice. He asserts that such deep-seated hatred creates a distorted view of the oppressed and reflects a refusal to acknowledge shared humanity across racial divides. 1. Prejudice as a Moral Disorder: Douglass contends that longstanding prejudices are tenacious and resistant to reason, akin to a moral disorder that sustains itself by distorting perceptions of those it deems inferior. He discusses how societal prejudices are often self-reinforcing, painting an unjust image of those who are marginalized, making it easier for individuals to rationalize hate. 2. Historical Context of Racial Prejudice: He draws from historical comparisons, noting that various races throughout history have suffered from similar prejudices. Even in England, the Norman conquest led to derogatory stereotypes against the Saxons, which persisted despite the Saxons' cultural and intellectual contributions over centuries. 3. The Impact of Racial Prejudice on African Americans: Douglass highlights the systemic challenges faced by African Americans, who bear visible markers of their race that expose them to discrimination and violence. Despite being free from slavery, they remain shackled by societal prejudice, which continues to diminish their opportunities and dignity. 4. Injustice in Legal and Social Systems: The speaker illustrates the pervasive nature of racial prejudice across American life, where individuals of color encounter bias in various arenas—employment, education, and justice systems. This systemic bias casts a shadow over their achievements and rights, leading to a societal view that unjustly presumes guilt and incompetence based on race. 5. Challenging Prejudice: Douglass questions the notion that racial prejudice is an intrinsic feature of human nature. He posits seven critical points that argue against the idea that color prejudice is an invincible trait, including the existence of societies devoid of such biases and the potential for individuals to overcome prejudices within themselves. 6. The Role of Society in Reinforcing Prejudice: He emphasizes that societal constructs foster prejudice, leading individuals to justify their biases. He warns against the dangers of power dynamics, suggesting that oppression fosters justifications for degradation, where the oppressed are deemed inferior by their oppressors. 7. Paths of Progress: Douglass expresses hope for future racial harmony, noting that improved education and moral character among African Americans would gradually dismantle entrenched prejudices. He encourages continued advocacy for justice and equality, urging society to recognize the shared humanity that transcends color. In subsequent addresses, Douglass further articulates the implications of Supreme Court decisions that deny civil rights and protections to African Americans. He critiques the failure of the judicial system to uphold justice, leading to a devaluation of the promises of freedom and equality. Douglass's impassioned appeals underscore the importance of recognizing the shared dignity of all people and the ongoing struggle for true equality within American society. Ultimately, he advocates for relentless efforts toward social justice and civil rights, envisioning a future where racial distinctions yield to a more inclusive definition of humanity. Douglass's sentiments resonate with modern discourses on race relations, emphasizing the need for self-reflection, societal change, and the unwavering belief that systemic injustices can be dismantled through collective action and moral resolve.

Key Point: Challenging Prejudice

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing at the crossroads of your own beliefs, facing the ingrained prejudices that society around you has instilled. Frederick Douglass's insistence that these biases are not an unchangeable part of human nature, but rather societal constructs that can be challenged and dismantled, invites you to take a moment for profound self-reflection. You realize that the shackles of prejudice don’t just bind the oppressed; they can also weigh down those who perpetuate them. In this realization, you find inspiration to question not just the world around you but your own thoughts and assumptions. You realize that by actively challenging your own biases and advocating for equality, you aren’t just working toward a fairer society; you are participating in a legacy of progress that transcends racial lines. Douglass empowers you to believe in the possibility of change, urging you to contribute to a collective movement toward justice, where recognition of shared humanity can ultimately replace the distorted views of the past.

Chapter 15 | A Fervent Hope for the Success of Haiti: An Address

Frederick Douglass, in a series of impactful addresses, delivers powerful messages that resonate with themes of independence, self-reliance, and the dignity of labor, reflecting his steadfast belief in the potential of individuals, especially those from marginalized backgrounds. 1. Douglass commends the progress made by the United States in embracing universal human rights, contrasting it with past norms of exclusion based on race. His words highlight a nation transformed, one that now shows sincere friendship and optimism towards Haiti and its leadership under President Hyppolite. 2. He proudly presents Haiti at the World’s Columbian Exposition, emphasizing the significance of its pavilion, built with great care and resources. Douglass lauds the nation’s dedication to representing itself on an international stage, devoid of shame about its history or identity. He articulates that Haiti stands firm among the civilized nations of the earth, proud of its independence and accomplishments. 3. Douglass further articulates the remarkable courage exhibited by Haitians in their struggle for freedom against formidable opponents. He draws parallels between Haiti’s fight for independence and that of America, arguing that Haiti’s victory was achieved against overwhelming odds and despite being painted inaccurately as a savage conflict. He asserts that every act of violence from the Haitian revolution was mirrored by the French invaders, emphasizing the morality of their cause. 4. Touching on the theme of self-made men, Douglass identifies those who rise from adversity, achieving success through unwavering effort and resilience. He characterizes self-made men as those who surmount significant obstacles without the usual privileges and advantages. Douglass acknowledges the hard work necessary for success, positing that true achievement stems from persistent effort and character, rather than luck or circumstance. 5. The addresses convey a broader philosophical outlook on human potential and the essence of manhood. Douglass posits that true greatness is a reflection of one's ability to strive, to adapt, and to labor with purpose. He emphasizes that the road to success requires effort and determination, with labor as the foundation of self-improvement and social progress. 6. He makes an appeal for respect for labor and advocates for an environment where individuals, regardless of their past or upbringing, have equal opportunities to succeed. Douglass stresses the importance of providing conditions that enable personal growth and asserts that with the right support, even the most disadvantaged can thrive. 7. In proclaiming the significance of self-education and the cultivation of knowledge, Douglass presents historical figures as exemplars of perseverance and ingenuity. He recounts the stories of notable individuals, both black and white, who have overcome obstacles to achieve greatness, reinforcing the belief that determination can triumph over adversity. 8. Douglass concludes by acknowledging the critical role of societal conditions that promote meritocracy, asserting that it is through diligent work and unyielding resolve that opportunities are created. He decries the residues of prejudice and inequality that still plague society, urging for a collective embrace of equality and respect for all individuals, thereby cultivating an environment conducive to all people’s success. Through his eloquent addresses, Douglass not only uplifts the narrative of communities of color but also fortifies the universal quest for dignity and respect, encapsulating the resilient spirit of humanity striving for progress.

Chapter 16 | Lessons of the Hour: An Address

In January 1894, Frederick Douglass delivered a powerful address, "Lessons of the Hour," seeking to address the dire state of African Americans in the United States, specifically in the Southern states. The essence of Douglass's speech can be distilled into several critical points. 1. Purpose and Motivation: Douglass opened by asserting the essential need for a noble intent when addressing an audience. His purpose was to speak out for the oppressed African American community, representing voices often silenced amid the prevailing narratives that misrepresented them. 2. The Urgency of the "Negro Problem": Douglass highlighted that the issue of race relations was not merely a local problem confined to the South; it was a national concern that demanded immediate attention. The existence of eight million African Americans subjected to egregious injustices posed a threat not just to their lives but to the moral fabric and security of the nation itself. 3. Lynching and Mob Violence: He pointed to the alarming rise of mob law in the South, where lynchings had reached unprecedented levels. Douglass characterized the savage violence against black individuals as a national disgrace, noting that white men were increasingly becoming victims of mob hysteria as well, thus broadening the implications of unchecked lawlessness. 4. Misplaced Accusations: The crux of Douglass’s argument revolved around the unjust accusations leveled at black men, particularly regarding assaults on white women. He argued that such charges were often fabricated or exaggerated, leading to brutal acts of violence without due process. To this end, no evidence or due legal procedure was involved in these mob actions. 5. Challenging the Narrative: The address served as a counter-narrative to both Northern and Southern perspectives that portrayed African Americans as inherently guilty or criminal. Douglass emphasized the fallacy of generalizing the actions of a few individuals to an entire race. He urged the audience to question the credibility of mob justice and recognize the skewed motivations behind these charges propagated by those in power. 6. The Role of Education and Suffrage: Douglass argued against the notion that ignorance among African Americans justified disenfranchisement. He asserted that it was the denial of education and suffrage that perpetuated their plight. He contended that empowering African Americans politically and socially was crucial for their advancement and the healing of the nation. 7. A Call for Justice: Concluding his address, Douglass urged for a return to justice and constitutional rights for all citizens, advocating for the protection of the rights of the oppressed. He called for all individuals, especially those in positions of power, to rise to the occasion and cultivate a nation founded on equality and justice. In essence, Douglass’s speech not only served as a robust defense of African Americans against violent oppression but also as a clarion call for justice, equality, and active engagement from all Americans in resolving the issues stemming from racial injustice.

Key Point: The Role of Education and Suffrage

Critical Interpretation: Frederick Douglass’s powerful assertion about the vital need for education and suffrage to empower African Americans is a timeless reminder of the importance of knowledge as a tool for liberation. Imagine yourself standing in a world where opportunities for education are scarce; the very pathway to your dreams seems blocked by societal barriers. Yet, Douglass’s words ignite a flame within you, urging you to not only seek knowledge for yourself but to advocate for access to education for others. It's a call to action that transcends race and history—it challenges you to recognize that true empowerment stems from education and the right to participate in the democratic process. In your own life, consider how you can harness the power of education to uplift not just yourself, but your community, standing as a testament to Douglass’s vision of justice and equality. Every quest for knowledge becomes a step towards dismantling ignorance, fostering understanding, and affirming the inherent dignity of every human being.