Last updated on 2025/04/30

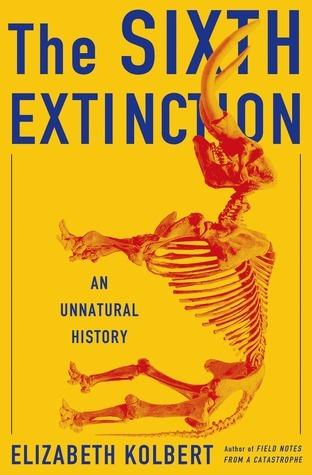

The Sixth Extinction Summary

Elizabeth Kolbert

Humanity's role in the planet's dramatic biodiversity loss.

Last updated on 2025/04/30

The Sixth Extinction Summary

Elizabeth Kolbert

Humanity's role in the planet's dramatic biodiversity loss.

Description

How many pages in The Sixth Extinction?

336 pages

What is the release date for The Sixth Extinction?

In "The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History," Elizabeth Kolbert masterfully weaves together personal narrative, scientific research, and historical context to illuminate the urgent and alarming reality of the ongoing mass extinction event caused by human activity. With a compelling blend of storytelling and investigative journalism, Kolbert travels across the globe, from the depths of the Amazon rainforest to the coral reefs of the Caribbean, showcasing the fragile ecosystems that are teetering on the brink of collapse. As she unveils the interconnectedness of life on Earth and the profound impact of climate change, habitat destruction, and invasive species, Kolbert challenges readers to confront the stark question: Are we, in our quest for progress, writing the final chapter of a story that has unfolded over millions of years? This provocative exploration not only sheds light on the current crisis but also implores us to take action before it’s too late, making it an essential read for anyone concerned about the planet’s future.

Author Elizabeth Kolbert

Elizabeth Kolbert is an acclaimed American journalist and author noted for her insightful exploration of environmental issues and the impacts of climate change. A staff writer for The New Yorker, Kolbert combines in-depth reporting with a compelling narrative style, engaging readers with complex scientific concepts in relatable ways. Her extensive work reflects her dedication to raising awareness about the urgent challenges facing the planet, a commitment that is prominently showcased in her Pulitzer Prize-winning book, "The Sixth Extinction." In this seminal work, she examines the ongoing biodiversity crisis and its implications for the future, drawing on her experiences traveling to various ecosystems and interviewing leading scientists.

The Sixth Extinction Summary |Free PDF Download

The Sixth Extinction

Chapter 1 | THE SIXTH EXTINCTION

In this opening chapter of "The Sixth Extinction," Elizabeth Kolbert chronicles the alarming disappearance of the Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus zeteki) and the broader implications it has for biodiversity and environmental health. The narrative begins in El Valle de Antón, Panama, a quaint town nestled in a volcanic crater known for its abundance of golden frog figurines. These frogs, once a common sight in the area due to their striking coloration and toxicity, have been vanishing at an alarming rate, leading scientists to realize that an undefined crisis was underway. 1. The initial decline of the golden frogs was first identified by an American graduate student in the rainforest, where she noticed a severe reduction in frog populations during her studies. This decline spread rapidly, marking the beginning of a catastrophic event that would lead many species, including those in the near vicinity of El Valle, to near extinction. Various biologists, alarmed by the rapid loss, attempted to establish a conservation effort to save some individuals, but their efforts came too late. 2. As Kolbert explores this issue further, she reflects on an article she read that suggested the world may be experiencing its sixth mass extinction. Previously, five significant extinction events have profoundly altered biodiversity on the planet. The current situation for amphibians, particularly golden frogs, indicates that this mass extinction may be unfolding before our eyes. 3. The chapter transitions to the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center (EVACC), an establishment designed to safeguard threatened amphibian species, including the endangered golden frogs. Here, the frogs are kept in elaborate tanks, mimicking their natural habitats, offering them a semblance of normalcy as biologists work to uncover a solution. Director Edgardo Griffith shares the emotional toll of losing these amphibians and expresses his deep commitment to conserving them. 4. The mysterious cause behind the mass frog die-off is identified as a chytrid fungus, which has been rapidly spreading and decimating amphibian populations across the globe. This fungus disrupts the frogs' ability to absorb critical nutrients, leading to death. The spread of this pathogen, largely facilitated by human activities and the global movement of species, raises concerns about the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the impact of human actions on biodiversity. 5. Despite significant efforts, including constructing a public exhibit at EVACC to educate about the crisis, scientist Paul Crump expresses doubts about the possibility of reintroducing golden frogs to their natural habitat, given the persistent threat posed by the chytrid fungus. There is a poignant tension between the hope of revival and the grim reality of continued extinction. 6. Moreover, Kolbert highlights the current extinction rates, particularly alarming for amphibians, which are now considered the most endangered animal class on earth. The extinction rate among amphibians is estimated to be as much as 45,000 times higher than the natural background rate, drawing attention to the widespread decline of various species globally. 7. Invoking the personal experiences of biologists and herpetologists like David Wake, who initially dismissed the alarming trends in frog populations, Kolbert illustrates the shocking shift from disbelief to urgency within the scientific community. Her narrative paints a grim picture that combines a sense of wonder for the natural world and the stark reality of its rapid decline. This chapter serves as an urgent call to recognize and confront the silent extinction crisis rapidly unfolding around us, emphasizing the potentially catastrophic implications for global biodiversity and the individual species that define our ecosystems. Through Kolbert's vivid storytelling and in-depth exploration, readers gain insight into both the larger ecological narrative and the intimate struggles of those dedicated to conservation efforts.

Key Point: The interconnectedness of ecosystems and human impact on wildlife.

Critical Interpretation: As you reflect on the heartbreaking tale of the Panamanian golden frog's decline, allow it to inspire a profound sense of responsibility within you. Imagine how your daily choices—what you buy, how you travel, and even the products you support—can ripple out to affect these delicate ecosystems. Recognize that the small actions you take in your everyday life can contribute to the broader fight against extinction. Whether it’s advocating for sustainable practices or supporting wildlife conservation, you are part of a larger story that can lead to healing our planet. This awareness can ignite a passion in you to protect not only the species at risk but to foster a more harmonious relationship with the natural world around you.

Chapter 2 | THE MASTODON’S MOLARS

In Chapter 2 of "The Sixth Extinction," Elizabeth Kolbert delves into the history of the concept of extinction through the story of the American mastodon, or Mammut americanum, and the pioneering work of naturalist Georges Cuvier. The chapter begins with an exploration of how children grasp the idea of extinction early in life, yet the notion is fundamentally complex and was not always recognized in scientific discourse. 1. The historical narrative around extinction reveals that ancient scholars, such as Aristotle and Pliny, did not entertain the idea of a historical progression for animals. Instead, they viewed species as parts of an unbroken chain of being. Despite evidence suggesting otherwise—fossils and remains of long-extinct creatures—scientific thought did not account for species disappearing. This reluctance continued until revolutionary France, when the idea of extinction began to emerge more clearly, particularly through Cuvier’s work. 2. Cuvier’s examination of bone remains, particularly those of the mastodon, was pivotal. The first significant mastodon find in the early 18th century included massive bones recovered from a sulfurous marsh near Cincinnati, Ohio. These finds sparked intrigue but confusion regarding classification, as contemporary taxonomies limited understanding to currently extant species. 3. As Cuvier correctly identified, the mastodon represented an entirely distinct species rather than just a variant of existing animals like elephants or mammoths. His painstaking analysis allowed him to categorize extinct species, leading to the recognition that they were indeed lost forms of life. Cuvier's assertions about extinction initially met with skepticism began to gain acceptance as he identified more extinct vertebrates. 4. The chapter details Cuvier’s ascent in Paris, where he became an influential figure at the Museum of Natural History. His lectures, which proposed that various extinct species had perished due to catastrophic events, garnered attention and laid the groundwork for a new understanding of life on Earth. Cuvier’s ideas were compelling enough to stir public interest and were supported by empirical evidence gathered from fossil findings. 5. Cuvier’s discoveries led to a dramatic expansion of the list of known extinct species. With bold claims about a world previous to ours filled with lost species, he fueled a fascination with paleontology and the hunt for fossilized remains. Cuvier's meticulous study of evidence formed a foundation that would categorize and define the study of extinct species in a systematic manner. 6. Intriguingly, while Cuvier established extinction as a genuine phenomenon, he opposed evolutionary ideas, arguing instead that animals were perfectly adapted to their environments. He believed that catastrophic events led to mass extinctions, rather than gradual evolution. This contradiction between acknowledging extinction yet denying evolution mirrors the complex nature of scientific understanding at the time. 7. The chapter concludes by highlighting Cuvier's profound yet flawed assertions regarding the causes of extinction, his views shaped by the prevailing insights of his time. Although some of his claims about catastrophic events and species extinction have been refined by modern science, the foundational work he laid out paved the way for future paleontology and our understanding of both extinction and evolutionary biology. Through the tale of the American mastodon and Cuvier's pivotal contributions, Kolbert weaves a rich historical narrative that illustrates how our understanding of life, death, and extinction has evolved, shedding light on the forces that have shaped the natural world.

Chapter 3 | THE ORIGINAL PENGUIN

In Chapter 3 of "The Sixth Extinction," Elizabeth Kolbert explores the relationship between geological theories and the historical extinction of species, focusing on the great auk (*Pinguinus impennis*). This chapter provides a detailed account of the scientific debates of the 19th century, primarily between William Whewell's "catastrophism" and Charles Lyell's "uniformitarianism." Whewell coined the term "catastrophist" in 1832, positioning it in contrast to Lyell’s perspective that changes in the Earth's surface occurred slowly and gradually over time. The dichotomy between their viewpoints laid the foundation for understanding both geological and biological evolution, significantly influencing Charles Darwin's theories of natural selection. 1. Whewell and Lyell's Theories: The chapter introduces William Whewell, who coined the term "catastrophist," and contrasts him with Charles Lyell, who argued that geological changes occur gradually. Lyell’s principle—"the present is the key to the past"—highlighted slow changes like erosion and sedimentation as the main drivers of geological formations, while dismissing the notion of sudden catastrophic events. 2. Darwin's Voyage and Influence of Lyell: Darwin's journey aboard the HMS Beagle is presented as pivotal to his development of evolutionary theory. Introduced to Lyell's *Principles of Geology* before embarking, Darwin employed Lyell's ideas to interpret geological formations he encountered. For instance, he realized that uplifted marine shells on volcanic islands supported Lyell's gradual change theories. This accumulation of evidence fueled Darwin's burgeoning understanding of evolution. 3. The Great Auk's Extinction: The chapter transitions to discuss the great auk, a flightless bird driven to extinction by human activities. It outlines how the great auk was once abundant—similar to modern penguins—yet became vulnerable due to extensive hunting and exploitation as sailors discovered its nesting grounds. By detailing the behaviors and habitats of auks, Kolbert illustrates the impacts of human interaction with the natural world. 4. Interplay between Evolution and Extinction: Kolbert argues that Darwin's theory of natural selection inherently included extinction, linking the emergence of new species with the disappearance of old ones. Both processes were framed as aspects of life's continuous evolution, with natural selection eliminating less competitive species. 5. Human-Caused Extinction: The chapter culminates in a critical examination of human-caused extinction events, contrasting them with Darwin's gradual theories. While Darwin acknowledged extinction driven by natural selection, Kolbert emphasizes exceptions where human exploitation decisively led to the rapid disappearance of species like the great auk and the Charles Island tortoise. This highlights the trouble within Darwin's theory regarding humanity's role in nature, raising questions about whether humans occupy a distinct category in natural history. Through engaging narratives and scientific discussions, Kolbert elegantly interweaves the themes of evolution, extinction, and the intricate relationship humans share with their environment, ultimately prompting readers to reflect on humanity’s responsibility toward biodiversity and conservation.

Key Point: Human-Caused Extinction

Critical Interpretation: As you delve into the grave reality of human-caused extinction illustrated by the tale of the great auk, you can’t help but feel a stirring sense of urgency. The narrative echoes the profound truth that your actions, no matter how small, can ripple through the vast expanse of nature. It urges you to reflect on your daily choices—how you consume, how you engage with the environment, and how you advocate for conservation. This chapter inspires you not only to be aware of your impact but also empowers you to become a steward for biodiversity. Each effort, whether it’s reducing waste or supporting sustainable practices, allows you to play a pivotal role in preventing further extinctions and ensuring that future generations inherit a thriving planet. You hold the potential to forge a change, reminding you that while extinction rates may escalate, your commitment to preserving life can carve a different path.

Chapter 4 | THE LUCK OF THE AMMONITES

In Chapter 4 of Elizabeth Kolbert's "The Sixth Extinction," we are introduced to the geological and paleontological significance of Gubbio, an Italian hill town, and its pivotal role in unveiling the asteroid impact hypothesis related to the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period. This chapter features the following key elements: 1. Historical Context: Gubbio's narrow streets and stone piazzas echo a timeless quality, rooted in its historical significance, including its connection to Dante Alighieri's exile in 1302. Its geological layers serve as a record of Earth’s distant past, with the Gola del Bottaccione gorge revealing nearly a hundred million years of geological history through its limestone strata. 2. Discovery of the Cretaceous Extinction Evidence: Geologist Walter Alvarez's chance discovery of a clay layer in Gubbio during the 1970s led to a groundbreaking revisitation of extinction events. He noticed a significant change in foraminifera—tiny marine creatures that served as index fossils—suggesting an abrupt extinction rather than a gradual decline, correlating with the extinction of reptiles like dinosaurs. 3. Iridium Anomaly and Impact Hypothesis: Alvarez and his father, Luis, devised a method to measure iridium levels in the clay layer, a metal abundant in meteorites but rare on Earth. Their findings indicated an unprecedented spike in iridium, proposing that this material came from an asteroid impact. This hypothesis was later supported by findings from locations across the globe, ultimately identified as the Chicxulub crater in Mexico. 4. Skepticism and Controversy: The Alvarezes faced significant backlash from the paleontological community, which held tightly to gradualist views of extinction processes. Skeptics critiqued their claims, insisting that extinctions could not be explained by a singular catastrophe, and emphasizing a slow, evolutionary understanding of extinction. 5. Validation Through New Evidence: As more geological evidence emerged, including shocked quartz and indications of a massive tsunami, support for the impact hypothesis grew. This culminated in the recognition of various iridium layers globally, reinforcing the notion of a catastrophic event that led to a mass extinction. 6. Ammonite Extinction: The narrative also delves into ammonites—a group of marine invertebrates that thrived for over 300 million years and ultimately went extinct at the K-T boundary. Through the lens of paleontologist Neil Landman, we learn about the characteristics of ammonites, how their reproductive strategies may have contributed to their vulnerability during the catastrophic event, and the discovery of new species in New Jersey that exemplified their past diversity. 7. Implications of Extinction: The chapter concludes by reflecting on the broader implications of extinction and survival, emphasizing that current life forms, including mammals, are descendants of organisms that survived the turmoil, though not due to superior adaptation. The lessons from ammonites serve as a cautionary tale about the fragility of life and the unpredictable nature of survival in the face of dramatic environmental changes. Overall, Kolbert’s chapter intricately weaves historical, scientific, and philosophical threads, highlighting the ongoing evolution of thought surrounding extinction events and the complex interplay between life and catastrophic occurrences in Earth’s history.

Chapter 5 | WELCOME TO THE ANTHROPOCENE

In the intricate narrative of Chapter 5 from "The Sixth Extinction" by Elizabeth Kolbert, the concept of the Anthropocene epoch is introduced and scrutinized through the framework of both geological history and scientific paradigms, particularly emphasizing the ongoing extinction crisis. The chapter begins by recounting a 1949 psychological experiment at Harvard that demonstrated how individuals tend to overlook conflicting information until it becomes undeniably evident, leading to significant shifts in understanding—an analogy drawn to the history of extinction science. 1. The notion of extinction as a scientific concept emerged relatively recently; prior to the late 18th century, extinction was not widely recognized. The pivotal contributions of naturalists like Georges Cuvier, who catalyzed a shift in perspective by acknowledging that life had a history marked by loss, remind us of the gradual evolution of scientific ideas. The chapter emphasizes Kuhn’s theory of paradigm shifts: the illustration of how disruptive data is either ignored or rationalized until it culminates in a crisis, resulting in profound insights and new frameworks. 2. The narrative then navigates through geological history, highlighting five major extinction events, with a particular focus on the Ordovician extinction approximately 444 million years ago. Zalasiewicz, a stratigrapher, guides the exploration of Dob’s Linn in Scotland, emphasizing the fossil record of graptolites and their demise during this time. His studies reveal that the transition from diverse life forms to barren landscapes occurred suddenly, likening it to a tipping point similar to other extinction events. 3. The chapter also explores the evolving scientific theories surrounding mass extinctions, illustrating the shift from ideas of periodicity and asteroid impacts to understanding the complexities of climate changes. For instance, the end-Ordovician extinction is currently attributed to glaciation events that dramatically altered habitats and ocean chemistry, shedding light on the intricate interplay of organisms within their environments. 4. Contrasts are drawn between extinction events: while the end-Ordovician is linked to a global cooling event, the end-Permian catastrophe involved catastrophic greenhouse gas emissions leading to extensive loss of biodiversity. The narrative illustrates how each extinction event is unique, shaped by specific environmental circumstances and evolutionary responses. 5. As the exploration of geological epochs expands, the Anthropocene is introduced as a new epoch defined by human impact. Crutzen’s introduction of the term challenges the traditional categorizations of geological history, arguing that human activity has become a significant geological force. Zalasiewicz and colleagues advocate for the formal recognition of the Anthropocene, positing that the current era will leave behind distinct stratigraphic signatures due to climate change, altered ecosystems, and extinction events that humans have instigated. 6. The ongoing human-induced extinction and its implications on future evolution signal a profound shift in the planet's history. The adaptability of species, such as rats, which have thrived amidst human disruption, reflects broader ecological dynamics. This brings forth a consideration of what the future holds for both surviving and evolving species, as human activities have irrevocably shaped the biosphere. In conclusion, this chapter weaves together history, psychology, and geology to illustrate the monumental shifts in understanding life on Earth, framed by the undeniable impact of human activities. As we confront the realities of extinction and climate change, the question arises: what legacy will we leave behind, and how will future generations of life adapt in the geologic record we’ve created?

Key Point: The Anthropocene and Our Impact

Critical Interpretation: As you delve into the implications of the Anthropocene epoch introduced in Chapter 5 of 'The Sixth Extinction,' consider how your actions shape the world around you. The stark reality that human activities serve as a geological force should inspire you to reflect on your personal footprint in nature. Each choice you make, from reducing waste to advocating for sustainable practices, plays a role in defining the legacy you will leave behind. Embrace the power of your decisions; recognize that you possess the ability to influence not just your immediate environment but the very fabric of the ecosystems that future generations will inherit. Your awareness and proactive engagement can transform a narrative of extinction into one of coexistence and renewal, encouraging you to become an agent of change in this pivotal era of history.

Chapter 6 | THE SEA AROUND US

In Chapter 6 of "The Sixth Extinction," Elizabeth Kolbert explores the profound effects of increasing carbon dioxide levels on marine ecosystems, particularly at Castello Aragonese, a small island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. The chapter begins with an engaging description of the island and its castle, shaped by the geological forces of plate tectonics that also trigger volcanic activity and release carbon dioxide into the sea. The narrative shifts as Kolbert accompanies marine biologists Jason Hall-Spencer and Maria Cristina Buia to observe the sea vents, where carbon dioxide is abundant and acidic conditions are mimicked. This acidic environment serves as a real-time preview of future ocean conditions, critical for understanding the broader implications of rising CO2 levels. 1. Ocean Acidification and CO2 Levels: Since the industrial revolution, humanity has released approximately 365 billion metric tons of carbon into the atmosphere, contributing significantly to the increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels—to over 400 parts per million, the highest in at least 800,000 years. The oceans, which cover 70% of the Earth’s surface, absorb much of this CO2, resulting in a drop in pH levels. Currently, ocean surface waters are 30% more acidic than they were in 1800, and without a reduction in emissions, a decline to a pH of 7.8 is anticipated by the century's end. 2. Impact on Marine Life: The experiments conducted near Castello Aragonese highlight the bleak future for marine ecosystems. As acidity increases, the biodiversity of affected regions diminishes drastically. Kolbert notes that in areas with lower pH, many species, particularly calcifiers like barnacles, mussels, and corals, show significant declines or are entirely absent. For example, a third of species surveyed in vent-free areas were not found in areas corresponding to predicted future acidity levels. 3. Calcifiers at Risk: Kolbert emphasizes the plight of calcifying organisms, which are crucial to marine ecosystems and vulnerable to acidic conditions. The rising acidity hampers their ability to build shells and skeletons from calcium carbonate, essential for their survival. The environment near the vents effectively illustrates how organisms struggle to adapt when pH levels exceed their tolerance limits. 4. Historical Context of Oceanic Change: The chapter also ties contemporary issues to historic events, suggesting that rapid changes in ocean chemistry have been linked to past mass extinctions. While many species may thrive in acidified waters, the overall biodiversity is expected to decline, resembling patterns seen during previous extinction events. 5. Urgency and Future Projections: Kolbert concludes by emphasizing the unprecedented rate of CO2 release due to human activity. Current projections suggest that if trends continue, future marine ecosystems could face catastrophic shifts, raising concerns about the legacy of the Anthropocene era. The chapter powerfully conveys a sense of urgency, underscoring the necessity for immediate action to mitigate climate change and protect ocean ecosystems. Through vivid descriptions and detailed analysis, Kolbert highlights the growing crisis of ocean acidification and its implications for marine life, presenting a compelling case for the urgent need to address human-induced climate change.

Key Point: The Urgency for Immediate Action

Critical Interpretation: As you immerse yourself in the haunting imagery of marine ecosystems struggling against the relentless tide of ocean acidification, let it ignite a fire within you to advocate for change. The stark reality that coral reefs—a cornerstone of ocean biodiversity—are facing catastrophic decline due to our actions is a call to arms. Imagine standing at the precipice of a future where vibrant underwater landscapes become ghostly remnants of their former selves, and know that you possess the power to alter this course. Your choices today, from reducing your carbon footprint to supporting sustainable practices, can echo through generations, shaping a world where marine life flourishes rather than falters. This is not just a distant scientific concern; it’s an immediate responsibility that requires your engagement. Step into the role of protector and steward of the planet, and thus, inspire others to join in this crucial battle against climate change.

Chapter 7 | DROPPING ACID

Half a world away from historic Castello Aragonese, One Tree Island, located at the southern tip of the Great Barrier Reef near Australia, surprises travelers with its coral rubble rather than sandy beaches. This island, entirely composed of varying forms of coral rubble, was formed during a significant storm approximately four thousand years ago. Despite its seemingly deserted appearance, it hosts a small research station operated by the University of Sydney, attracting scientists routinely drawn to its unique ecological significance. 1. The stark reality of One Tree Island is illustrated during a memorable encounter as a loggerhead turtle attempts to lay eggs on the jagged coral. This instance highlights the struggles faced by wildlife in challenging environments, compounded by human warnings about the dangers of the surrounding waters, reflective of the precarious balance of life in these ecosystems. 2. The One Tree Island Research Station, modest in construction, serves as a hub for global scientific teams who come to study coral initiatives and marine life. Graffiti left by previous visitors humorously captures the essence of their scientific pursuits, showcasing the ongoing examination of corals amidst the looming threat of ocean acidification, as hinted by the American-Israeli group's fence post: “DROPPING ACID ON CORALS.” 3. Historical context is given through references to Captain James Cook’s first contact with the Great Barrier Reef in 1770 and the subsequent theories developed by naturalists like Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin, who contributed key insights into the origins and complexities of coral reefs. Darwin’s subsidence theory, pivotal in understanding reef formation, only gained acceptance after substantial geological evidence corroborated his findings in the mid-twentieth century. Coral reefs, constructed by tiny organisms called polyps, are not only vital for marine biodiversity but also function as resilient structures that, much like human construction, involve rigorous collective effort spanning generations. Billions of these polyps unify to build vast communities that provide habitat and sustenance for an estimated half a million marine species. Yet, the ongoing health of coral reefs faces imminent threats, with experts warning that these ecosystems could be among the first to face ecological extinction in the current era, primarily due to human-induced climate change. 4. The dangers presented by ocean acidification emerge prominently through the research at One Tree Island, led by climate scientist Ken Caldeira, who warns that increasing atmospheric CO2 levels risk altering ocean chemistry. Current trends predict unsustainable conditions for coral reefs by mid-century, underscoring a critical need for urgent climate action. Caldeira's experiences illustrate the day-to-day challenges of collecting data amidst the ebb and flow of tides, emphasizing the pressing nature of their research. The contrast between snorkel explorations discovering breathtaking marine diversity and the grim reality of coral degradation serves to highlight the paradoxes faced within these ecosystems. 5. A significant development in understanding coral responses to acidification occurred at Biosphere 2, where researchers first recognized that coral growth is closely tied to the saturation state of seawater, affecting their capacity to build calcium carbonate structures. Current predictions indicate that a future without stable saturation levels may result in the collapse of coral reefs, as existing pressures from overfishing, water pollution, and climate change compound the effects of acidification. Despite historical setbacks, such as reef gaps following mass extinctions, the current fate of the Great Barrier Reef is more precarious than ever. Studies vary in their optimism about coral survival, yet consensus suggests that, without intervention, the continuation of healthy reef ecosystems is at serious risk. Leads from research conducted on One Tree Island mirror alarming trends observed in reefs globally. 6. As scientists delve deeper, snorkeling adventures reveal the stunning yet fragile beauty of One Tree Island’s reef systems. Observations of diverse marine life reinforce the legendary status of coral reefs as vibrant ecosystems teeming with life. Bone-chilling realities surface as bleaching phenomena amplify under stress from climate change. 7. In a synchronized coral spawning event, researchers witness the natural wonder of reef reproduction, highlighting a crucial moment in the life cycle of corals. Yet as they aim to study the impacts of acidification on this critical reproductive phase, insights glean from the mass spawning point towards the fragility of these ecosystems amidst escalating anthropogenic pressures. In summary, this chapter underscores the complex interdependence of life and the environmental threats faced by coral reefs like those in the Great Barrier Reef. As spectacular and strangely resilient as these ecosystems are, the urgency of recognizing and mitigating the influences of human activity has never been more apparent. The potential loss of coral reefs carries far-reaching implications for global biodiversity and marine life, making the future all the more uncertain if ongoing threats are not addressed.

Chapter 8 | THE FOREST AND THE TREES

In Chapter 8 of "The Sixth Extinction" by Elizabeth Kolbert, the author, alongside forest ecologist Miles Silman, explores the extraordinary biodiversity of forests, particularly in the context of climate change. Standing on a mountain in eastern Peru, they are surrounded by Manú National Park, a haven for rich flora and fauna. Silman emphasizes the intricate life histories of trees, noting that understanding these complexities adds depth to their appreciation, similar to wine. 1. The Biodiversity of Manú National Park: Manú National Park is one of the most biodiverse regions in the world, containing approximately one out of every nine bird species globally and over a thousand tree species within its boundaries. The diversity here contrasts starkly with that of other regions, such as Canada's boreal forest, highlighting the rich tapestry of life present in the tropics. 2. The Impact of Climate Change on Tropical Species: While global warming is often framed as a threat predominantly to cold-climate species, Silman argues that tropical species, constituting the majority of Earth's biodiversity, may face even greater risks. As the climate continues to change, many will struggle to adapt. 3. Speciation and the Latitudinal Diversity Gradient: The chapter delves into historical and scientific theories attempting to explain the remarkable diversity seen in the tropics compared to the poles. These include the rapid evolutionary rates seen in warmer climates, the historical stability of tropical regions, and environmental factors that encourage speciation through isolation. 4. The Mechanisms of Forest Ecosystems: Silman's work has led to the establishment of meticulously analyzed tree plots across varying elevations in Peru, which reveal significant differences in species richness and composition. The study aims to monitor how tree species respond to changing climate conditions, which are expected to force numerous species to migrate upwards to cooler temperatures. 5. The Race Against Time: As temperatures rise, trees and other species will need to keep pace with climate change. Some species, like those in the genus Schefflera, have shown promising rates of movement. However, the swift rate of current climate change poses challenges that may exceed the capacity of many trees and organisms to adapt. 6. The Future of Forest Ecosystems: Silman foresees that climate change will not only alter species composition but also disrupt established ecological relationships—for better or worse. While some species may thrive under new conditions, many will struggle to survive, leading to a restructuring of entire ecosystems. 7. The Species-Area Relationship and Extinction Risk: Silman discusses the significant implications of the species-area relationship (SAR) on biodiversity conservation. This principle states that larger areas typically harbor more species. As human activities shrink habitats, extinction rates are forecasted to rise dramatically, especially if climate conditions shift rapidly. 8. The Long-Term Consequences of Climate Change: As evidenced by historical climate shifts, species on Earth have traditionally migrated or adapted to survive. However, the unprecedented rate of current climate change presents a unique existential threat. Silman warns that many species simply may not move fast enough to cope, raising concerns about future biodiversity loss and ecological collapse. In conclusion, Kolbert’s narrative illustrates the precarious balance of tropical ecosystems, the resilience of certain species, and the ominous challenges posed by climate change. As ecosystems face profound shifts, the interplay of adaptability and extinction unfolds dramatically within the rich forests of the tropics.

Chapter 9 | ISLANDS ON DRY LAND

In Chapter IX of Elizabeth Kolbert's "The Sixth Extinction," the focus is on Reserve 1202, a twenty-five-acre block of untouched rainforest nestled in the Amazon, surrounded by deforested land. This area is part of an extensive ecological project known as the Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project (BDFFP), which has been investigating the impact of fragmentation on biodiversity for over thirty years. The project arose from a collaboration between cattle ranchers and conservationists, spearheaded by biologist Tom Lovejoy, who sought to utilize the alterations in forest structure caused by ranching for scientific study. 1. The Concept and Importance of Reserve 1202: Reserve 1202 functions as a representative “island” amidst a sea of cleared land, with dense vegetation that hosts diverse wildlife. It is documented extensively, offering a unique perspective on the dynamics of forest fragments in the Anthropocene. 2. Extent of Human Impact: Approximately fifty million square miles of the planet are ice-free, and humans have transformed over half of this land. The BDFFP sheds light on how fragmentation affects species diversity, indicating dire consequences even in seemingly small forest patches. Ecologists have begun to assess human impact through the lens of “anthromes,” categorizing areas based on human usage, which complicates traditional biogeographic metrics. 3. Fragmentation and Its Consequences: The BDFFP has documented the phenomenon of “relaxation,” where isolated ecosystems gradually lose species over time, transitioning from diverse habitats to more depauperate ecosystems. This process illustrates the fragility of small populations, as the chance of extinction rises due to environmental changes and random events. 4. North of Manaus: The narrative provides insights through the experiences of ornithologist Mario Cohn-Haft and his detailed explorations of avian life. He emphasizes the staggering diversity of bird species in the Amazon, and how many may go undetected due to their cryptic nature. 5. Monocentric Views of Biodiversity: The chapter highlights the complexity of ecosystems where numerous interdependent relationships exist. Army ants, for instance, create a unique niche environment that supports an array of species, showcasing the intricate connections within the ecosystem. The reliance on specific species for habitat stability illustrates the delicate balance of these ecosystems. 6. Long-Term Trends and Future Implications: Lovejoy postulates that fragmentation may lead to broader atmospheric shifts and reinforce the importance of habitat connectivity. The findings from BDFFP serve as cautionary indicators of the ramifications of human actions on biodiversity, especially in the context of climate change. 7. Extinction Rates and Our Understanding: The chapter juxtaposes historical calculations of extinction rates with contemporary research, revealing discrepancies in our understanding of species loss and highlighting the challenge of monitoring insect populations. Data gaps underscore the urgent need for better conservation efforts as the Amazon faces increasing threats. Through vivid descriptions of the rainforest, animal interactions, and research endeavors, Kolbert elucidates the profound impacts of deforestation and habitat fragmentation on biodiversity in the Amazon. Reserve 1202 and the BDFFP epitomize the urgency of conservation efforts in light of human-induced changes to the natural world. As Kolbert concludes, the interconnectedness of species highlights both the richness and vulnerability of these ecosystems, framing the narrative of extinction within the broader context of the Anthropocene.

Chapter 10 | THE NEW PANGAEA

In Chapter 10 of "The Sixth Extinction" by Elizabeth Kolbert, the narrative compellingly intertwines the fate of the little brown bat, Myotis lucifugus, with broader themes of ecological disruption. 1. The chapter opens during a winter bat census in New York, highlighting the unique behaviors of true hibernators like the little brown bat and the alarming discovery of widespread mortality linked to white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease caused by Geomyces destructans. Wildlife biologists recognized the severity of the crisis when encountering dead bats en masse, marking a troubling indication of ecological distress. 2. The spread of white-nose syndrome the following winters resulted in catastrophic population declines across numerous states. This phenomenon underscores the fragility of ecosystems in the face of introduced pathogens, suggesting that bats, once abundant, may not recover due to the slow reproductive rates and continued exposure to the invasive fungus. 3. Kolbert connects this local devastation to Darwinian principles of biogeography, previously disrupted by natural barriers. She elaborates on historical migration patterns and species distribution, emphasizing how isolation historically enhanced biodiversity. Yet, human activities—through global trade and travel—accelerate species introductions, effectively creating a “New Pangaea,” where the consequences of invasive species become more pronounced. 4. The chapter describes the complexities of species invasions, comparing them to Russian roulette; while many introduced species fail to thrive, some can become invasive, often due to a lack of natural predators in their new environments. Notably, certain newcomers exploit unprepared ecosystems, significantly altering local biodiversity and threatening native species. 5. Kolbert discusses the role and impacts of invasive species, exemplified by the brown tree snake in Guam and the introduction of various pathogens. The latter disrupts existing ecological balances by decimating species unprepared for new threats. This impacts not just individual species, but entire ecosystems, leading to long-term consequences for biodiversity. 6. The ongoing spread of white-nose syndrome reflects the intertwined fates of bat species and their environments. As biologists document declining populations, the urgency for conservation grows ever more pressing. The chapter concludes on a note of despair, conveying the stark reality of losing these vital species and urging reflection on the broader implications of human interference with natural processes. Through these interconnected narratives, Kolbert highlights the fragility of ecosystems amidst rapid environmental change, revealing how historical and contemporary forces converge to threaten the intricate web of life that sustains our planet.

Chapter 11 | THE RHINO GETS AN ULTRASOUND

In Chapter 11 of "The Sixth Extinction," Elizabeth Kolbert introduces us to Suci, a Sumatran rhino residing at the Cincinnati Zoo. Born in 2004, Suci serves as a living link to a species with ancient roots, her lineage tracing back twenty million years to the Miocene era. This chapter explores the efforts of conservationists working to avert the extinction of the Sumatran rhino, a species now teetering on the brink, with fewer than a hundred individuals estimated to remain in the wild. 1. Rhino Physiology and Reproductive Challenges Kolbert describes a poignant scene in which Dr. Terri Roth, a leading figure in conservation efforts, conducts an ultrasound on Suci to assess her reproductive status. Sumatran rhinos are solitary by nature and females only ovulate in the presence of a male—a significant hurdle since Suci's nearest potential mate is ten thousand miles away. Roth's attempts to artificially inseminate Suci offer a glimpse into the sophisticated, often frustrating efforts required to breed these endangered animals. The disappointment upon discovering that Suci had not ovulated underscores the challenges faced in captive breeding programs aimed at conserving a species on the brink. 2. Historical Overview and Conservation Efforts Once widespread across a significant portion of Southeast Asia, the Sumatran rhino faced drastic population declines due to habitat loss and poaching. A conservation conference in 1984 initiated a captive breeding program, but the early years were riddled with setbacks including high mortality rates due to disease and misunderstanding of their dietary needs. Kolbert captures the suspense and tension of the breeding program, detailing Roth's innovative strategies to create fertile conditions for reproduction. 3. Success Against the Odds The efforts at the Cincinnati Zoo have led to the birth of three historically significant offspring, Andalas, Suci, and Harapan. While these births are a remarkable achievement, they fail to offset the broader existential crisis faced by their wild counterparts. Kolbert notes the irony that despite human-driven extinction events bringing rhinos to the brink, it is now human intervention that may offer a slim hope for their survival. 4. The Wider Context of Extinction The author extends the narrative beyond the Sumatran rhino to highlight the precarious status of various megafauna globally. Threats faced by the Javan and Indian rhinos, alongside the significant decline of black and white rhinos, illustrate a global crisis impacting many charismatic megafauna. The chapter discusses cultural perceptions of these animals, underscoring the emotional connections humans have with them even in captivity. 5. The Historical Precedence of Megafauna Extinction Kolbert interweaves historical insights about megafauna extinction, citing the work of early naturalists like Georges Cuvier and Alfred Russel Wallace. Their observations raise questions about the causes of historical extinctions—whether climate change or human activity played primary roles. 6. Human Impact on Extinction Dynamics Focusing further on the role of humans, Kolbert presents compelling arguments favoring the theory that early human hunters significantly influenced the extinction timeline of large mammals. The timing of human migrations often coincides with extinction events, suggesting a more profound relationship between humanity and ecological disruption than previously understood. 7. Conclusion and Reflection on Conservation The chapter concludes by reflecting on the impact of human choices on biodiversity, posing tough questions about mankind's historical and ongoing roles as drivers of extinction. The fate of Suci and her species is symbolic of a larger narrative regarding the Anthropocene's effect on planet Earth—a reminder that the extinction of entire species is not merely a relic of the past but an urgent contemporary issue that demands attention and action. In sum, Kolbert masterfully weaves the intricate story of Suci, capturing the essence of conservation efforts, the complex interactions between species and their environments, and the historical precedents that guide our understanding of extinction today. The juxtaposition of Suci's life against the backdrop of human impacts on biodiversity serves as a pressing call to recognize our responsibilities as stewards of the planet.

Chapter 12 | THE MADNESS GENE

In Chapter 12 of "The Sixth Extinction," Elizabeth Kolbert delves into the intriguing history of Homo neanderthalensis, commonly known as Neanderthals. This exploration begins in the Neander Valley near Cologne, where the first Neanderthal bones were unearthed in 1856. The area has since transformed into a modern museum reminiscent of the Paleolithic era, complete with interactive exhibits such as a "Morphing Station" that humorously illustrates visitors' likenesses to Neanderthals. 1. The Neanderthals, having existed in Europe and parts of the Middle East for over a hundred thousand years, left behind a wealth of artifacts, including sophisticated tools for hunting and skinning animals and evidence suggesting they crafted clothing and built shelters during a period dominated by harsh climatic conditions. However, around thirty thousand years ago, these hominids disappeared. 2. Numerous theories have been proposed about their extinction, ranging from climatic changes and volcanic activity to diseases and competition with modern humans. The latter appears to be a significant factor, as Homo sapiens arrived in Europe approximately forty thousand years ago, leading to a stark decline in Neanderthal populations. Genetic evidence reveals that modern humans interbred with Neanderthals, with most non-Africans carrying up to four percent Neanderthal DNA. 3. The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, headed by Svante Pääbo, is at the forefront of Neanderthal genetic research. Pääbo's ambitious project to sequence the Neanderthal genome seeks to uncover the genetic distinctions that set modern humans apart from their ancient relatives, particularly focusing on what enabled humans to build complex societies and far-reaching technologies. 4. Neanderthal bones were initially mistaken for those of other animals, sparking a mix of scientific curiosity and controversy in the context of Darwinian evolution. Early interpretations depicted Neanderthals as brutish and primitive, largely due to misunderstandings of their skeletal structures. However, subsequent research painted a different picture, showcasing their intelligence and social behaviors, including the potential for care and even burial rituals. 5. Studies involving Neanderthal tools and remains suggest they were skilled toolmakers, yet their technological advances appeared stagnant over millennia. Contrastingly, modern humans exhibited a remarkable capacity for innovation and adaptation, which ultimately played a role in the extinction of Neanderthals. Insights from archaeologist Ralph Solecki imply Neanderthals may also have had spiritual dimensions, shown through evidence of burial practices. 6. Current research approaches DNA as a language that tells the story of a species over time, and the fragmentary nature of ancient DNA poses significant challenges for researchers. The extraction of usable DNA from ancient samples requires meticulous handling, and significant breakthroughs have revealed hybridization between Neanderthals and early modern humans, leading to the "leaky replacement" hypothesis: that our ancestors not only displaced Neanderthals but also genetically mingled with them. 7. As the book moves toward contemporary issues, Kolbert reflects on the fate of modern great apes, whose populations are under severe threat of extinction due to human activities. This harrowing parallel illuminates the fragile structure of our shared evolutionary history and the continued impact of humans on the environment, reflecting that while we may have pushed Neanderthals and other archaic humans to the brink, we are now repeating these patterns with the remaining great apes. 8. The chapter concludes with a poignant reminder of our species' unique drive for exploration and innovation, potentially stemming from a genetic predisposition. Pääbo's quest suggests that understanding the genetic underpinnings of what makes us human might reveal insights into not only our past but also our future, nudging us towards the depths of our own humanity and responsibility toward other species. Through Kolbert's narrative, readers are drawn into a web of historical discovery, genetic exploration, and ethical contemplation regarding our shared past with Neanderthals, shaping our understanding of identity and survival in an ever-evolving world.

Key Point: Embracing our connection to Neanderthals encourages us to reflect on our role in the ecosystem.

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing in a dimly lit museum, gazing at a Neanderthal skull, and suddenly feeling a spark of recognition; you share a story with this ancient being. Realizing that you carry a piece of their DNA ignites a profound sense of responsibility towards the natural world. This chapter invites you to recognize that the choices you make today echo through time, just as Neanderthals left their mark on history. Whether it's engaging in conservation efforts or simply making sustainable choices, you are connected to the legacy of both humanity and its ancestors. This awareness inspires you to act thoughtfully, ensuring that future generations inherit a world where all species can thrive, not just humans.

Chapter 13 | THE THING WITH FEATHERS

In Chapter 13 of "The Sixth Extinction" by Elizabeth Kolbert, the author explores the poignant intersection of human action and species extinction through the lens of conservation efforts and the fragility of biodiversity. A visit to the Institute for Conservation Research at the San Diego Zoo reveals the somber reality of efforts to preserve endangered species, such as the po`ouli, a bird that has essentially become extinct with only cells preserved in liquid nitrogen. This effort underscores a paradox; while liquid nitrogen is a last resort for melting biodiversity, it highlights the extent of human-driven extinction, arguing whether such measures are enough or merely a stopgap. 1. The Frozen Zoo: The facility, known as the Frozen Zoo, houses nearly a thousand species’ cell lines preserved in extreme cold. The poignant narrative of the po`ouli illustrates how, despite all efforts, some species have already faded into oblivion. This reflects a dangerous trend as many more plants and animals are on the brink of extinction. The author contemplates the chilling prospect that humans, despite our capacity for care and progress, have let so many species dwindle to such desperate circumstances. 2. Human Capacity for Change: Kolbert recounts history showing that human beings can be zealous advocates for the environment, evidenced by landmark legislation like the Endangered Species Act and conservation success stories such as the California condor and whooping crane. Major efforts involving creative strategies, like the use of puppets to raise condor chicks or ultralight aircraft to guide whooping cranes, demonstrate significant commitment to conservation. Yet, the author questions whether these efforts can mitigate the broader extinction crisis when many species still face overwhelming threats. 3. The Individual Case of Kinohi: Through the lens of Kinohi, a Hawaiian crow living in captivity, the author illustrates the peculiarities and challenges of saving a species on the brink of permanent disappearance. Kinohi, odd and isolated, represents the complexities faced in captive breeding programs, highlighting how human interventions can be as strange as they are necessary. It is a reminder that the human effort to stave off extinction involves intimate, often awkward, interventions into the lives of other species. 4. The Broader Extinction Context: Kolbert reflects on the pattern of extinction events throughout Earth's history, comparing the current Sixth Extinction to past events precipitated by natural disasters, yet identifies modern human actions as a unique catalyst. The nuanced discussion emphasizes that the rate of change outpaces species' ability to adapt, leading to a cascading collapse of biodiversity. Therefore, the narrative posits that it is not merely human care that will determine our future, but our fundamental actions and impacts on ecosystems. 5. The Future of Homo sapiens: In a sobering conclusion, the chapter examines the dual nature of humanity's relationship with the planet—its potential for both irreversible destruction and remarkable innovation. The author warns that our reliance on the earth’s biosystems cannot be underestimated because continued ecological disruption can equally threaten human survival. As extinction unfolds, future generations of life on Earth will be shaped by the choices made today, emphasizing the crucial responsibility humanity holds in determining the fate of countless species and the planet itself. In summary, Kolbert's exploration in this chapter serves as a vital reflection on extinction's reality—a call to recognize our role in conservation against a backdrop of history and our profound ethical obligation to protect the biodiversity that sustains life on Earth.