Last updated on 2025/05/03

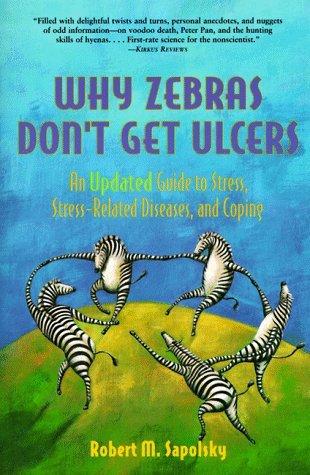

Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers Summary

Robert M. Sapolsky

Stress and Its Impact on Health and Behavior.

Last updated on 2025/05/03

Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers Summary

Robert M. Sapolsky

Stress and Its Impact on Health and Behavior.

Description

How many pages in Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers?

434 pages

What is the release date for Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers?

In "Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers," renowned biologist and neuroscientist Robert M. Sapolsky takes readers on a fascinating journey through the intricate relationship between stress and health, revealing why creatures like zebras, who face immediate dangers in the wild, experience stress far differently than humans, who grapple with chronic anxieties of modern life. By blending engaging anecdotes with cutting-edge science, Sapolsky unveils the profound impacts of prolonged stress on our bodies and minds, arguing that while zebras flee from predators, our perpetual worry leads to a host of health issues, from ulcers to heart disease. This thought-provoking exploration not only uncovers the biological mechanisms behind stress responses but also offers insights into how we can harness this knowledge to mitigate stress's harmful effects, ultimately inviting readers to rethink their approach to life’s challenges.

Author Robert M. Sapolsky

Robert M. Sapolsky is a renowned American biologist, neuroscientist, and author, celebrated for his pioneering research on stress and its effects on the body and brain. With a Ph.D. in neurobiology from Rockefeller University and an impressive career as a professor at Stanford University, Sapolsky combines a rich background in biology with a talent for writing that engages both scientific and general audiences. His work encompasses a wide range of topics, including the behavior of wild baboons and the implications of stress in human life, making him a distinguished figure in the field of behavioral biology. In addition to "Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers," Sapolsky has authored several other books, essays, and lectures that explore the intersections of science, nature, and human experience, solidifying his reputation as a key voice in science communication.

Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers Summary |Free PDF Download

Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers

Chapter 1 | WHY DON'T ZEBRAS GET ULCERS?

In "Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers," Robert M. Sapolsky explores the complex relationship between stress, health, and disease, emphasizing how human experiences of stress differ significantly from those of other animals, particularly in the context of modern society. This foundational chapter delves into numerous key concepts, setting the stage for the intricate discussion of stress-related diseases that follows. 1. The Experience of Stress: Sapolsky opens with a relatable scenario of lying awake at night, consumed by anxiety about upcoming challenges such as presentations or tests. He illustrates the tendency to catastrophize feelings and sensations, turning mundane worries into severe health concerns—such as fears of serious illnesses like cancer or brain tumors. This phenomenon reflects a more extensive understanding of stress in contemporary humans, who are less likely to worry about infectious diseases due to advancements in medicine. 2. Evolution of Disease Patterns: The text notes that the leading causes of death in the early 20th century were primarily infectious diseases, contrasting starkly with the chronic diseases prevalent today, such as heart disease and cancer. As humans have gained longer lifespans and better health, our worries have migrated from immediate life-threatening conditions to enduring health issues that develop over time. 3. The Role of Stress in Disease: Sapolsky argues that stress is a significant factor in many chronic diseases, demonstrating the intricate connections between emotions, biology, and health. He emphasizes that stress responses, which evolved for immediate physical threats, are ill-suited for dealing with long-term psychological stressors that characterize modern life. 4. Types of Stressors: He classifies stressors into three categories: acute physical crises (like predation), chronic physical challenges (like food scarcity), and psychological/social disturbances. Unlike animals, humans often create stress from thoughts and anxieties unrelated to immediate physical dangers, leading to overactivation of stress responses that can be harmful. 5. Homeostasis and Allostasis: The author introduces the concept of homeostasis—the ideal functioning state of the body—and expands it with the concept of allostasis, which accounts for how the body changes its set points in response to stress. This means that in the face of potential stressors, the body prepares itself collectively to maintain balance. 6. The Allostatic Load: Sapolsky discusses the "allostatic load," the cumulative burden of chronic stress on the body. When the body is frequently thrown out of balance and responds with prolonged stress, it suffers wear and tear, leading to an array of diseases. 7. The General Adaptation Syndrome: The author summarizes Hans Selye's theory of stress response, outlining the three stages: alarm (recognizing a stressor), resistance (mobilizing the body’s responses), and exhaustion (the eventual negative health effects of prolonged stress). Contrary to Selye's original notion that the body runs out of stress hormones, Sapolsky asserts that it is the continued activation of these systems that is harmful. 8. Physiological Reactions to Stress: The book describes how the body reacts to stress, including energy mobilization, increased heart rate, blood pressure, and the suspension of long-term bodily functions like digestion, growth, and reproduction. While these responses can be adaptive during acute stress, their chronic activation due to psychological stress can result in numerous health issues. 9. The Importance of Context: Sapolsky emphasizes the significance of context in understanding stress's effects. For animals, stress is often tied to immediate survival, while for humans, the psychological aspects can lead to harmful effects over time. The stress response may be beneficial in short bursts but detrimental when activated through psychological worry and anticipation. 10. Societal Influence on Stress: The text hints at how societal structure affects individuals' experiences of stress, suggesting that social position can contribute to the prevalence and impact of stress-related diseases, particularly for those from disadvantageous backgrounds. In summary, Sapolsky's work illuminates the profound impacts of chronic stress on human health, delineating how our modern experiences of stress and our psychological complexities have shifted the nature of disease from immediate physical threats to chronic health issues. Understanding these dynamics not only helps us comprehend stress-related diseases better but also outlines pathways for effective stress management and resilience building in an increasingly stressful world.

Key Point: Understanding and Managing Stress

Critical Interpretation: You can take a profound lesson from Sapolsky's exploration of stress and its impact on health. Rather than allowing anxiety over future challenges to consume you, consider how recognizing your stressors can empower you to transform them into manageable solutions. By approaching stress with awareness and intentionality, you can cultivate resilience and foster a healthier approach to life's inevitable challenges. Each time you feel stress creeping in, remind yourself that it's a natural response, and then actively work to find balance—be it through mindfulness, seeking support, or reframing your thoughts. This understanding can inspire you to navigate the complexities of modern life with greater ease, promoting not just your mental well-being, but your overall health.

Chapter 2 | GLANDS, GOOSEFLESH, AND HORMONES

In the exploration of how stress affects our physical health, there is an inherent connection between the brain and the body that is fundamental to understanding this phenomenon. This connection is remarkably intricate, as evidenced by the observation that even thoughts alone can trigger physiological responses without any direct physical activity. For example, merely thinking about stress or eliciting emotions such as anger or lust can lead to changes in the body; from heart rate and perspiration to hormonal secretions from glands like the pancreas and liver, the brain acts as a powerful command center. The communication pathways between the brain and various organs are largely governed by the autonomic nervous system, which can be divided into two branches: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous system is activated in response to stress, mediating functions necessary for immediate survival—often described as the "fight-or-flight" response. It releases adrenaline and noradrenaline (also known as epinephrine and norepinephrine), which prepare the body for action by increasing heart rate and redirecting blood toward muscles. In contrast, the parasympathetic system promotes relaxation and recuperation, mediating activities conducive to energy conservation and digestion when the body is not under immediate stress. 1. Master Gland Dynamics: The body’s hormonal activity is not solely governed by the peripheral glands, such as the adrenal glands or pancreas, but is facilitated by the brain, specifically the pituitary gland. Initially considered the "master gland," it is now understood that the brain's hypothalamus actually orchestrates the release of hormones from the pituitary that regulate various bodily functions. The hypothalamus secretes releasing and inhibiting hormones that influence the secretion of pituitary hormones, establishing a hormonal communication system crucial for adjusting the body’s response to stressors. 2. Stress Hormones: During stressful situations, several hormones are involved in the body's stress response. The release of glucocorticoids, particularly cortisol, is prompted by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus, which stimulates the pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). This hormonal cascade ultimately triggers glucocorticoids from the adrenal glands. These stress hormones serve critical roles in mobilizing energy and altering physiological functions to address immediate threats. Additionally, hormones like glucagon and various growth-related hormones can be inhibited, allowing energy to be redirected and prioritizing threats over non-urgent functions. 3. Gender Differences in Stress Response: Recent research has illuminated potential differences in how males and females experience and respond to stress. While the classical "fight-or-flight" model may apply more to males, females might exhibit a "tend-and-befriend" response that emphasizes social connectivity and nurturing behavior under stress. Hormonal factors, particularly oxytocin, are believed to facilitate this response in females, indicating that the stress response is more complex and nuanced than previously understood, involving both aggressive and socially supportive elements. 4. Complicated Stress Responses: It’s important to recognize that not all stressors elicit the same hormonal responses, nor do they activate the same physiological pathways uniformly. The stress reaction can vary based on the type, intensity, and psychological context of the stressor, leading to individual "stress signatures." For example, social stressors may heighten sympathetic responses while potentially diminishing glucocorticoid responses, which are more prevalent in passive, hopeless scenarios. This variability can also impact mental health outcomes, with distinct markers for anxiety and depression associated with different hormonal activities. In conclusion, the interrelationship between the brain and the body, mediated through the nervous and endocrine systems, is pivotal in shaping how we respond to stress. While acute stress responses can be vital for survival, consistent stress can lead to detrimental health effects, highlighting the importance of managing stress effectively to maintain overall well-being.

Chapter 3 | STROKE, HEART ATTACKS, AND VOODOO DEATH

In Chapter 3 of "Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers," Robert M. Sapolsky delves into the relationship between stress and cardiovascular health, illustrating how the body's physiological responses to stressors can lead to chronic health conditions such as heart disease. A sudden encounter with a lion is posed as a metaphor to explain the immediate physiological changes that occur under stress, particularly how the cardiovascular system ramps up to facilitate survival. 1. The activation of the cardiovascular stress response begins with the sympathetic nervous system, which increases heart rate and force of contraction. This response is essential for preparing the body to respond to immediate threats by directing blood away from non-essential functions, like digestion, and toward muscles. The role of glucocorticoids in amplifying this response is also emphasized, as they help to further stimulate the heart and blood vessels. 2. The section highlights the efficiency of blood flow redistribution during acute stress. While stress prepares the circulatory system for immediate physical action (like running away from a predator), chronic psychological stress can trigger these responses in inappropriate contexts, such as during everyday annoyances or deadlines, leading to maladaptive cardiovascular changes. 3. Chronic stress can lead to hypertension, as repeated activation of the stress response increases blood pressure over time, causing the heart and blood vessels to work harder. This creates a vicious cycle: higher blood pressure leads to thicker arterial walls, which in turn raises blood pressure further, increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases. 4. Stress is shown to promote the formation of atherosclerotic plaques by increasing the likelihood of vascular damage and the aggregation of harmful substances within the circulatory system. The chapter discusses how stress-induced hypertension leads to turbulence at the bifurcation points of blood vessels, causing minor injuries that attract inflammatory cells and result in plaque buildup—a precursor to heart attacks and strokes. 5. The risk of sudden cardiac death during intense emotional stress is discussed, highlighting that strong emotions can trigger fatal cardiac events due to the excessive sympathetic nervous system activation. Events such as extreme joy or sudden grief can precipitate heart attacks, illustrating the idea that both positive and negative stressors can have similar physical effects on heart health. 6. The chapter also addresses the increased cardiovascular disease rates in women, indicating how factors such as stress and social hierarchy impact female primates in ways that mirror human experiences. Current studies point to a link between chronic stress and lower estrogen levels, revealing that stress may elevate cardiovascular risks, particularly post-menopause. 7. An intriguing aspect covered is the phenomenon of "voodoo death," where individuals can die from stress-inducing beliefs or curses, showcasing the power of psychological perceptions on physical health. The dialogue around psychophysiological death highlights the interplay between mental states and cardiovascular collapse, reinforcing the idea that mental well-being significantly influences physical health. 8. Finally, the chapter suggests that personality traits, such as hostility or a Type-A personality, can modulate individual responses to stress, leading to varying risks for cardiovascular disease. While stress can trigger physiological responses beneficial for immediate survival, chronic activation of these systems due to psychological stress can prove detrimental over time, emphasizing the necessity for effective stress management for long-term health. In conclusion, Sapolsky's exploration in this chapter illustrates the dual nature of the stress response: although it is crucial for survival in the short term, its chronic activation poses significant risks for cardiovascular health, underscoring the importance of addressing stress in our daily lives.

Key Point: Understanding the chronic effects of stress on cardiovascular health

Critical Interpretation: Imagine you're navigating through your day, dealing with the usual pressures—deadlines, family obligations, social obligations. Now consider this: every time you feel that clenching in your chest or the rush of adrenaline, your body is responding as if it were facing a life-or-death situation. This realization can inspire you to rethink how you approach stress. By recognizing that frequent small stresses can lead to long-term damage to your cardiovascular system, you might be motivated to embrace mindfulness practices, prioritize relaxation, and cultivate healthier responses to everyday challenges. Such changes not only promote emotional well-being but can transform how you experience life by enhancing your physical health and longevity.

Chapter 4 | STRESS, METABOLISM, AND LIQUIDATING YOUR ASSETS

In Chapter 4 of "Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers," Robert M. Sapolsky provides an insightful analysis of how stress interacts with the human body's metabolism. When faced with danger, such as a lion chasing you, the body's immediate response is to mobilize energy from its stores to fuel muscles for a quick escape. This energy mobilization is a complex process predicated on the body's previous function of energy storage. 1. Energy Storage: Initially, food consumed is broken down into its simplest components: amino acids, glucose, and fatty acids. These components cannot be used immediately but are transported through the bloodstream to be reconstructed into proteins, sugars, and fats. Insulin plays a crucial role here by promoting the storage of these nutrients in their complex forms within fat cells (as triglycerides), muscles, and liver (as glycogen). 2. Energy Mobilization During Stress: In an emergency, the body's natural metabolism adapts to prioritize immediate energy supply over storage. The sympathetic nervous system is activated to suppress insulin secretion and promote the release of stress hormones like glucocorticoids. This triggers the breakdown of stored nutrients—glucose is released from glycogen; fatty acids and glycerol are mobilized from fat stores. Ultimately, muscle cells exercising during stress can override temporary blocks on nutrient uptake. 3. Chronic Stress and Health Impact: While a metabolic stress response is necessary during acute stressful situations, chronic activation of this response can lead to various health issues. Constantly mobilizing energy for perceived emergencies is not sustainable and inefficient. Just as repeated withdrawals from a bank incur penalties, excessive energy mobilization depletes the body's reserves and leads to fatigue, muscle atrophy, and increased risks of diseases like cardiovascular problems, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. 4. Diabetes and Stress: The chapter addresses the implications of chronic stress on diabetes types—juvenile (Type 1) and adult-onset (Type 2). In juvenile diabetes, the immune system attacks insulin-producing cells, leading to elevated glucose levels in the bloodstream, which can exacerbate complications. Stress further complicates management by increasing glucose and fatty acids, triggering insulin resistance in Type 2 diabetes. Chronic stress can accelerate the onset and complications of both diabetes types. 5. Metabolic Syndrome: Chronic stress contributes to metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions including hypertension, abnormal cholesterol levels, and insulin resistance, which collectively increase the risk of heart disease and other serious health problems. The interconnectedness of stress, metabolism, and these conditions underscores the importance of managing stress to prevent this syndrome's multifaceted health implications. 6. Holistic View of Metabolism: The chapter highlights the complex interactions in the body that govern energy regulation, emphasizing that various factors—influenced by lifestyle and stress—affect health outcomes rather than isolated issues. Understanding this interconnectedness can lead to better strategies for addressing stress-related health risks. This chapter ultimately portrays the body's energy management system as a sophisticated yet vulnerable network, underscoring the dire consequences of chronic stress on metabolism and overall health. The insights provided by Sapolsky emphasize a need for effective stress management strategies to mitigate associated health risks.

Chapter 5 | ULCERS, THE RUNS, AND HOT FUDGE SUNDAES

In this chapter, Robert M. Sapolsky explores the intricate relationships between stress, appetite, food consumption, and gastrointestinal function. He begins by acknowledging that various forms of food scarcity—such as not having enough food or water—are significant stressors that affect both animals and humans. Stress impacts eating behaviors in complex ways, resulting in reactions that can lead to either hyperphagia (increased appetite) or hypophagia (decreased appetite), depending on individual factors. 1. Impact of Stress on Eating Patterns: Stress changes our appetite, inhibiting it in certain contexts, like when a zebra is fleeing from danger—it doesn’t think about eating then. However, in some individuals, stress leads to increased eating, often driven by emotional needs or specific cravings for comfort foods like sweets. 2. Hormonal Regulation: The hormones involved in stress responses, particularly CRH and glucocorticoids, play conflicting roles in appetite regulation. CRH, which is released quickly during stress, tends to suppress appetite, while glucocorticoids released later serve to stimulate appetite and encourage energy storage, particularly for foods high in sugar and fat. The timing and levels of these hormones in the bloodstream determine whether one experiences an increased or decreased appetite during and after stress. 3. Physiological Responses: During stress, the body prioritizes immediate survival over digestion. The sympathetic nervous system is activated, reducing blood flow to the gastrointestinal tract and suppressing digestive functions. When the stressor ends, digestion resumes, potentially leading to significant changes in appetite and nutrient storage. 4. Body Fat Distribution: Stress not only alters appetite but also influences how and where the body stores fat. Glucocorticoids promote the accumulation of visceral (abdominal) fat, resulting in an "apple" shape, which has been associated with greater health risks compared to gluteal (hip) fat, which shapes a "pear." 5. Gastrointestinal Motility: Stress can also lead to gastrointestinal disturbances, such as diarrhea or constipation, linked to heightened large intestine contractions. In situations of acute stress, the body's response can lead to a rapid passage of contents through the intestines, resulting in diarrhea. Conversely, in prolonged stress, motility can be disrupted, leading to constipation. 6. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) often manifest during periods of high stress. Stress not only seems to increase the severity of symptoms in these cases but also influences the sensitivity of the gut to stressors. 7. Peptic Ulcers: The chapter concludes with a critical look at peptic ulcers, traditionally thought to be solely stress-related. While the discovery of the bacterium *Helicobacter pylori* has transformed understanding of their etiology, stress continues to play a significant role in their formation. Stress can exacerbate ulcer development through several biological mechanisms including disrupted blood flow, reduced protective mucosal defense, and increased gastric acid secretion. Throughout the chapter, Sapolsky underscores the multifaceted relationship between stress, appetite, digestive health, and the body's hormonal responses. Stress affects not only what we eat but also how our bodies manage and store food, with significant implications for health and well-being. By considering both psychological and biological factors, he illustrates the complexity of these interactions and their consequences for both physical and mental health.

Chapter 6 | DWARFISM AND THE IMPORTANCE OF MOTHERS

In this chapter of "Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers," Robert M. Sapolsky explores the complex relationship between growth, stress, and early maternal care, particularly focusing on how various forms of stress can influence physical and psychological development from prenatal stages through childhood. The interconnectedness of nutrition, hormones, and emotional well-being frame the narrative as foundational to understanding health across a lifespan. First, growth is conceptualized as a process that seems fantastical yet is indeed a biological reality—one fundamentally dependent on nutrients from food. Growth necessitates the acquisition of vital resources, such as calcium for bones and glucose for energy. Hormones, especially growth hormone, play crucial roles, facilitating the building of tissues, promoting cell division, and aiding in transforming nutrients into bodily components like bones and muscles. Various other hormones also influence growth, including insulin and sex hormones like estrogen and testosterone, with the latter impacting the growth trajectories of adolescents. Interestingly, excessive testosterone before the closure of growth plates can lead to shorter adult statures, indicating that hormonal balance is key in growth regulation. However, Sapolsky shifts the focus toward the detrimental effects of stress on growth, illustrating how psychosocial stressors can impede normal development, leading to conditions like stress dwarfism or psychosocial dwarfism. This phenomenon often correlates with extreme circumstances such as emotional neglect or psychological abuse. Children experiencing severe stress can exhibit halted growth trajectories despite adequate nutrition, revealing the profound influence of emotional and social environments on physiological processes. The chapter emphasizes the critical role of maternal stress during pregnancy, showcasing how prenatal exposure to stress can result in lifelong health consequences. For instance, fetuses exposed to famine learn to store nutrients more efficiently, leading to increased risks of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases later in life—a phenomenon known as metabolic programming. Evidence from historical events, like the Dutch Hunger Winter, illustrates how early malnutrition impacts health for generations. Notably, how a mother’s emotional state can affect fetal health adds another layer of complexity to prenatal development. Elevated glucocorticoids signal a stressful environment to the fetus, programming its future responses to stress and health risks. Postnatal maternal behaviors also play a significant role in determining a child’s growth and psychological resilience. The nurturing aspects of caregiving, highlighted by extensive research on animals and humans, show that affection and physical touch profoundly influence growth hormone levels and overall development. Furthermore, neglect or insufficient maternal care can contribute to anxiety and developmental issues in later life, emphasizing that emotional well-being is just as crucial as nutritional status. Fascinatingly, the effects of stress and caregiving extend beyond the immediate offspring; they can influence future generations, creating a cycle of stress-related health issues. Individuals who experience stress and trauma may unknowingly pass on these predispositions to their children, reflecting an intricate interplay between genetics, environment, and societal influences. In summary, this chapter presents a comprehensive view that underscores the necessity of nurturing, supportive environments for healthy growth and development. It argues that physiological processes cannot be detached from emotional and social contexts, illuminating how love and care are indispensable to the biological fabric of life. Stress, particularly in early life stages, emerges as a formidable force that shapes the trajectories of health and well-being. In conclusion, while definitive preventive measures against these developmental stressors are not guaranteed, awareness and remedial actions can foster resilience and healthier outcomes across generations.

Chapter 7 | SEX AND REPRODUCTION

Chapter 7 of "Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers" by Robert M. Sapolsky delves into the intricate relationship between stress and reproductive health, examining how physiological mechanisms are affected by stress in both male and female reproductive systems. The chapter presents an in-depth analysis of how stress, whether psychological or physical, can disrupt normal reproductive functioning in significant ways. 1. In male reproductive mechanisms, stress leads to decreased hormone production. The hypothalamus under stress releases less LH-RH (Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone), which subsequently results in decreased levels of LH (Luteinizing Hormone) and FSH (Follicle-Stimulating Hormone). This downregulation leads to diminished testosterone production and sperm production. Observations during physically stressful situations, such as surgeries or extreme psychological challenges, highlight acute declines in testosterone levels. Additionally, psychological stressors, such as social rank changes or challenging tasks, further exacerbate this decline. 2. Psychologically induced stress also affects erections and other aspects of sexual performance. Achieving an erection is a complex physiological process, requiring significant blood flow to the penis, which is mediated by the parasympathetic nervous system. Stress triggers a sympathetic nervous system response, constricting blood flow and making it difficult to maintain an erection. Men experiencing stress may enter a cycle of anxiety, where fear of performance issues leads to additional stress, further impairing erectile function. 3. In contrast, certain stressful situations may not negatively impact reproductive capabilities, especially in the context of mating. Some species exhibit a heightened reproductive response during mating competition, where stress hormones may even invigorate reproductive processes, resulting in a nuanced understanding of how stress affects reproduction across species. 4. Female reproduction mirrors many of these patterns. The female reproductive system, influenced by the fluctuation of hormonal levels throughout the menstrual cycle, similarly suffers during periods of stress. The secretion of hormones such as LHRH, LH, and FSH decreases under stress, impacting ovulation and menstrual regularity, potentially leading to conditions like amenorrhea (absence of menstruation). For example, conditions like anorexia nervosa, where there's intentional starvation, disrupt normal hormonal function, challenging reproductive capabilities. 5. Additionally, the presence of high levels of adrenal androgens due to stress can further inhibit reproductive mechanisms, complicating the dynamics of stress, hormonal regulation, and reproductive health in women. Women facing chronic high-stress environments, including extreme physical activity levels or caloric deficits, face extended menstrual cycles and increased risks of reproductive disorders. 6. The chapter discusses the implications of stress on fertility treatments, particularly high-tech assisted reproduction procedures like IVF (In Vitro Fertilization). The stress associated with such interventions may negatively affect their success rates. Various studies suggest that women experiencing heightened stress during these procedures are less likely to achieve successful outcomes. 7. Stress during pregnancy, both in humans and animals, shows a historical thread linking psychological disturbances and miscarriages. Elevated stress hormones can lead to reduced uterine blood flow, increasing risks of miscarriage or preterm labor. The evolutionary implications reveal how stress responses can adaptively terminate pregnancies in response to unfavorable conditions. 8. The cumulative evidence illustrates that reproductive health is multifaceted and intricately linked to stress mechanisms. While fundamental reproductive functions might withstand severe stress, the subtleties of sexual response are notably sensitive to stress-induced disruptions. Understanding these dynamics not only adds valuable insights into human reproductive biology but also underscores the nuanced interplay between stress and reproductive success. In summary, Sapolsky emphasizes that while stress can profoundly influence reproductive health, the resilience of certain reproductive mechanisms amidst extreme stress challenges the assumption that stress universally inhibits these biological processes. The exploration of stress in relation to reproduction invites further examination into the psychological and physiological intricacies that shape human experiences of sexuality and reproduction.

Chapter 8 | IMMUNITY, STRESS, AND DISEASE

The intricate relationship between stress, immunity, and disease presented in Chapter 8 of "Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers" by Robert M. Sapolsky offers profound insights into how the mind influences physical health. The emerging discipline of psychoneuroimmunology underscores the connection between psychological states and the immune system's functioning. Historically, the notion of an isolated immune system has been dismantled as we uncover the intricate interplay between our brain and immune responses. Stress acts as a disruptive force against immune function, with both acute and chronic experiences causing varying degrees of immunosuppression. 1. Understanding Stress and Immunity: The autonomic nervous system is interconnected with the immune system, allowing mental states to impact physical health. Research demonstrates that even simple psychological stimuli can provoke immune responses, illustrated via allergic reactions to artificial roses. The phenomenon of conditioned immunosuppression reveals that immune responses can be managed not solely by drugs but conditioned stimuli, supporting the strong link between cognition and immunity. 2. Immune System Fundamentals: The immune system is vital for defending against pathogens, relying on a complex network of white blood cells, specifically lymphocytes (T cells and B cells). T cells address infections through direct action, while B cells produce antibodies tailored to specific invaders. The capacity for memory enables the immune system to recognize and respond more efficiently to previously encountered pathogens. This intricate equipment distinguishes between the body’s own cells and those recognized as foreign threats. 3. The Effects of Stress on Immunity: Evidence since Selye’s pioneering work has shown that stress can atrophy immune tissues, limit lymphocyte proliferation, hinder antibody production, and destabilize communication among immune cells. Elevated glucocorticoids during stress suppress these immune aspects, highlighting why acute stress can be adaptive, but chronic stress often leads to detrimental immunosuppression. 4. Acute vs. Chronic Stress: When exposed to stress, the immune response may initially enhance, rallying "innate immunity" to respond to immediate threats, but prolonged exposure to stressors can result in significant immunosuppression, which ultimately increases vulnerability to infectious diseases and impacts overall health. This dynamic suggests an evolutionary nuance where the immune system must balance immediate defense mechanisms against long-term health maintenance. 5. Stress and Autoimmunity: The chapter explores the duality of how stress can exacerbate autoimmune diseases while glucocorticoids themselves are used as treatment to dampen immune responses. Immune dysregulation appears influenced by stress-induced fluctuations that may predispose individuals to autoimmune conditions, especially if recovery phases (phase B) fail to occur. 6. Research Confounds and Limitations: The complexity of linking stress to specific diseases creates challenges in establishing clear causal pathways. Many studies rely on retrospective data, which can introduce bias, and stress responses vary significantly among individuals. Additionally, studying chronic stress versus acute episodes requires carefully designed studies that account for lifestyle factors and individual differences. 7. Social Factors, Stress, and Disease Risk: Social isolation significantly impacts health outcomes, indicating that robust social support may buffer against the negative effects of stress on immunity, thereby influencing disease susceptibility. Psychological elements intertwine with lifestyle choices—individuals facing stress may engage in poorer health practices, compounding risks for diseases such as cancer. 8. Stress, Cancer, and Victim Blaming: The discussion culminates in examining the debated link between stress and cancer. While animal studies suggest stress affects tumor growth dynamics, human evidence remains inconclusive, often complicated by retrospective biases. Treatment approaches that reinforce the idea of self-responsibility for illness, like those proposed in popular health literature, risk laying undue guilt on patients. In conclusion, the exploration of stress, immunity, and disease opens a multifaceted discussion on the physiological implications of mental health. Understanding how stress shapes immune function is crucial for holistic health approaches, emphasizing the importance of stress management and supportive social structures in fostering resilience against physical illness. The continuing evolution of psychoneuroimmunology underscores the necessity for an integrated perspective in health care, addressing both the mental and physical facets of disease.

Key Point: The Impact of Stress on Immunity

Critical Interpretation: As you journey through life, take a moment to grasp the profound effect that stress has on your immune system. Imagine navigating a particularly demanding day—perhaps you feel overwhelmed by deadlines or personal challenges. Recognizing that this stress is not just a mental burden but a physical one as well can empower you to seek balance. Understanding the relationship between your emotional state and your body’s defenses encourages you to prioritize stress management techniques such as mindfulness, exercise, or social connection. By actively mitigating stress, you can bolster your immune system’s resilience, enabling you to better fight off illnesses and fostering a deeper sense of well-being. Embrace the idea that nurturing your mind is a vital investment in your physical health, allowing you to move through life with greater vigor and confidence.

Chapter 9 | STRESS AND PAIN

In Joseph Heller's *Catch-22*, an antihero named Yossarian debates the nature of pain and its existence. While pain is often described as a necessary warning system for bodily harm, Yossarian sarcastically questions why a benevolent deity would create such a miserable experience. He underscores the dual nature of pain: it serves crucial protective functions by informing us of potential danger, but it can also be unnecessarily debilitating, especially in cases of chronic illness. Those who lack the ability to feel pain (pain asymbolia) face significant risks, as the absence of pain leaves them unaware of injuries that could lead to severe damage or complications. The physiological mechanisms of pain perception reveal a complex interplay between pain receptors located throughout the body and their neural pathways communicating with the brain. Pain signals travel via different types of nerve fibers that transmit sharp versus dull pain, with spinal cord interneurons playing a vital role in modulating these signals. Sharp, acute pain triggers a quick response that motivates immediate removal from the source of danger, while dull, persistent pain encourages stillness to facilitate healing. 1. Pain serves a critical warning function, allowing us to avoid further injury and seek medical help, but can become debilitating when it persists without resolution. 2. Understanding the modulation of pain perspectives can be beneficial, as pain intensity can be significantly influenced by psychological factors. For example, the relief experienced during a massage when muscles are sore highlights how other sensations can alter pain perception. 3. Stress can buffer pain through a phenomenon known as stress-induced analgesia. This occurs when biological responses to stress release endogenous opioids, which dull pain perception, ultimately enabling individuals to function despite injuries. An example is the reduced pain medication requests from soldiers in battle compared to civilians with similar injuries. Research illustrates that the brain's interpretation of pain is deeply subjective, reflecting an individual's emotional context and situational awareness. For instance, novel findings show that patients with different views from their hospital windows require varying levels of pain relief. This indicates that the emotional state and surroundings affect one's experience of pain. 4. The concept of stress-induced analgesia becomes particularly relevant during situations of heightened stress, where physical injuries may go unnoticed due to the overwhelming focus on survival. However, the release of endogenous opioids can also lead to stress-induced hyperalgesia, wherein ordinary pain stimuli are experienced as more intense due to heightened emotional sensitivity to pain. 5. Chronic stress carries its own consequences. Continuous activation of the body’s opioid response to pain can lead to depletion, resulting in diminished pain relief over time. This peculiar temporary respite comes at the risk of enduring painful experiences once natural pain modulation wanes. Research into conditions like fibromyalgia reveals the complexities of pain perception in relation to stress and emotional response. Patients exhibiting stress-induced hyperalgesia often show heightened sensitivity and emotional responses to pain stimuli, showcasing the interplay between chronic stress, emotional states, and pain perception mechanisms. In summary, the intricate relationship between stress, pain, and the body's response systems illustrates both the protective and detrimental roles pain can play in our lives. Chronic stress can complicate these responses, affecting the balance between analgesia and heightened sensitivity, which ultimately demonstrates the multifaceted nature of pain perception and management. Understanding these mechanisms is critical in addressing chronic pain conditions and their treatment.

Chapter 10 | STRESS AND MEMORY

In this chapter, Robert M. Sapolsky delves into the intricate relationship between stress and memory, illustrating how various kinds of stress can both enhance and impair our ability to retain information. He begins with a poignant personal memory, recounting the excitement he felt during a significant event which remains imprinted in his mind. Such vivid recollections underscore a universal experience: major, emotionally charged moments—whether joyful or traumatic—are much more easily remembered than mundane daily occurrences. This sets the stage for the discussion on how stress factors into the process of memory formation. 1. Stress Enhances Memory: Short bursts of mild to moderate stress have been shown to bolster cognition and memory retention, especially related to emotionally loaded events. Research demonstrates that when a highly arousing narrative is presented, individuals are more likely to remember the core emotional components rather than the mundane details of the story. This phenomenon relates to how stress activates the brain's sympathetic nervous system, enhancing the availability of neurotransmitters like norepinephrine, crucial for memory consolidation. 2. Stress Disrupts Memory: Conversely, high-stress levels or prolonged stressors can severely impair memory retrieval, resulting in what Sapolsky refers to as an inverse-U relationship. Research shows that chronic stress can inhibit explicit memory formation while sparing implicit memory. This highlights a critical distinction between memory types; explicit memory depends heavily on the hippocampus, while procedural memory—like riding a bicycle—remains intact even under significant stress. 3. Mechanisms of Memory Formation: To understand how stress impacts memory, it is imperative to comprehend the mechanics of memory systems. Memories are categorized as either short-term or long-term, often mediated through structures such as the hippocampus and the cortex. The author emphasizes that memories are not recorded in isolation within individual neurons but are instead represented by patterns of activity across networks of neurons. Learning occurs through strengthening these connections, facilitated by neurotransmitters like glutamate. 4. Neural Networks and Memory Access: Memory retrieval involves activating multiple interconnected neural networks. For example, trying to recall a painting's artist might engage several associated networks, leading to the desired memory when sufficiently activated. Stress can alter this dynamic; mild stress enhances cognitive frameworks for memory access, while high-stress scenarios disrupt these networks, making memory retrieval increasingly challenging. 5. Stress and Neurobiology: Research indicates that the physiological effects of stress on the brain can lead to neuronal atrophy in the hippocampus, exacerbating the effects of trauma or disease. Chronic stress can diminish the growth of new neurons, particularly detrimental to aging populations whose brains may already be compromised. 6. Impact on Health and Medicine: The implications of stress-related memory issues extend beyond individual memory performance; they raise concerns about the use of glucocorticoids (the body's primary stress hormones) in clinical settings. For instance, high levels of glucocorticoids during neurological crises may worsen potential brain damage, making the stress response counterproductive in certain medical emergencies. 7. Clinical Evidence: Sapolsky cites various studies demonstrating that conditions like Cushing's syndrome and PTSD correlate with hippocampal atrophy and memory loss, further illustrating how prolonged stress impacts cognitive function and neuronal health. 8. Memory and Aging: Research suggests that gradual increases in glucocorticoids with aging are linked to a decline in hippocampal size and function. This relationship amplifies concerns about chronic stress potentially accelerating neurodegenerative processes. As the chapter concludes, Sapolsky prompts readers to reflect on the delicate balance of stress in life; it can serve as a catalyst for memory enhancement but, if amplified and prolonged, can lead to significant cognitive decline and damage. This intricate interplay underscores the crucial role of stress management, particularly in a fast-paced, modern environment where stressors abound. As he prepares to explore further implications in subsequent chapters, he leaves us contemplating the long-term health of our brains in relation to stress and memory. In light of this chapter’s insights, it becomes clear that maintaining a healthy memory hinges significantly on managing stress effectively.

Key Point: Mild Stress Enhances Memory

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing at the precipice of a thrilling moment—your heart races, the air is electric with anticipation. This is where mild stress turns electric memories into vivid snapshots of your life. You recall that high-stakes presentation, the exhilaration of a first date, or a triumphant victory—all burned into your memory because they were laced with just the right amount of stress. This chapter reveals that by embracing short bursts of stress, you can enhance your memory's vividness, sharpening your ability to remember life's pivotal moments. Choose to view challenges not as threats but as opportunities to create lasting memories that define your journey.

Chapter 11 | STRESS AND A GOOD NIGHT'S SLEEP

The complexities of sleep, its interaction with stress, and the detrimental effects of sleep deprivation are vividly illustrated in an anecdote from the author’s own experience as a new parent. The chaos of a sleepless night with a newborn reflects a broader reality: a lack of sleep is a significant stressor, and being stressed can impede one’s ability to sleep. This forms a vicious cycle that becomes difficult to break. Firstly, sleep is divided into distinct stages, each with unique functions. Shallow sleep (stages 1 and 2) allows for easy awakening, while deep sleep (stages 3 and 4), also known as slow-wave sleep, is critical for physical restoration. Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep, which follows, is where dreaming occurs and the brain exhibits heightened activity. During slow-wave sleep, the brain’s energy restoration takes precedence, while REM supports emotional processing and memory consolidation. Research demonstrates that sleep deprivation disrupts cognitive processes, particularly memory. Sleep helps consolidate new information, converting short-term memories into long-term ones. Various sleep stages contribute differently; for example, REM sleep enhances emotional memory. The absence of adequate sleep tends to lead to elevated glucocorticoids—stress hormones—that compromise memory and cognitive performance. Sleep deprivation itself acts as a stressor, activating the body’s stress response and disrupting hormone levels essential for recovery and mood regulation. While sleeping, the body typically experiences a decline in stress hormones, allowing for restoration. However, the absence of sleep means these stress hormones remain elevated, creating a compounded effect that hinders cognitive functioning and emotional well-being. Moreover, stress can interfere with sleep quality, exacerbating insomnia. The hormone Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) plays a pivotal role, as it is linked to arousal and anxiety. Elevated levels of CRH lead to fragmented sleep, predominantly decreasing slow-wave sleep—critical for physical recovery. Individuals grappling with stress often wake more easily and experience less restorative rest, perpetuating a cycle of fatigue and heightened stress. The dynamics between sleep and stress highlight a troubling feedback loop: insufficient sleep coincides with increased stress, while stress reduces sleep quality. Anticipating poor sleep can raise stress levels even before one tries to rest. A study illustrates this, indicating that subjects aware of a shorter sleep duration experience elevated stress hormones even while they sleep, illustrating how psychological stress can intrude upon sleep. Understanding the bidirectional relationship between stress and sleep is vital. People living under chronic stress or irregular schedules, such as shift workers, are at an increased risk for various health issues, including cardiovascular problems and impaired memory. The societal shift towards shorter sleep durations due to lifestyle demands further complicates the situation, with implications for overall health and cognitive function. In summary, sleep deprivation not only serves as a stressor but is also exacerbated by stress, creating a worrisome cycle that demands careful attention. With fundamental shifts in sleeping patterns and increasing demands on time, understanding and prioritizing sleep is crucial for both mental and physical health.

Chapter 12 | AGING AND DEATH

In the exploration of aging and mortality, the text delves into the emotional awakening that often begins in adolescence when individuals first confront the reality of death. This realization opens a deep well of emotions, driving behaviors that range from selfishness to altruism and reigniting the human quest for meaning and permanence. The author reflects on the frailty and discomfort associated with aging—the physical and cognitive declines that many associate with this stage of life, such as dementia, immobility, and a sense of invisibility within family dynamics. Yet, there is a stark contrast in cultural perceptions of aging, particularly from studies conducted with populations like the Masai, who view aging positively as a journey toward wisdom and respect rather than a decline. 1. Elderly Wisdom vs. Western Fear of Aging: Many non-Western cultures celebrate aging, eagerly anticipating the transition to elder status, which contrasts sharply with the often grim perception of aging in Western societies. The author expresses envy for those untroubled by the ideas surrounding mortality, wishing for a similar acceptance. While recognizing the impending challenges of aging, the author also conveys an optimistic picture painted by gerontologists who study successful aging. Research indicates that many older adults experience a decrease in negative emotions and an increase in overall happiness, often retaining a positive perception of their health and relationships. Quality of social interactions tends to improve, leading to a richer sense of connection and satisfaction in later years. 2. Stress Response and Aging: However, a significant aspect of aging comes with a diminished ability to cope with stress. As individuals age, they lose some resilience and capacity to manage stress effectively. Several factors contribute to this, including weakened cellular responses and reduced physiological adaptability when faced with stressors such as exercise or illness. The body struggles to mount an adequate stress response, and over time, the elderly may experience an overstimulation of stress hormones, which can lead to detrimental health outcomes, such as increased disease susceptibility. In some species, such as salmon, the release of glucocorticoids during stress appears to lead to premature aging and death, exemplifying how stress and hormonal changes can entwine with aging. In humans, chronic stress presents tangible threats to health, accelerating conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular disease, which are prevalent in older populations. 3. Glucocorticoid Effects on Aging: The text highlights a concerning feedback loop in which elevated levels of glucocorticoids exacerbate aging processes. As individuals age, a dysfunction in the brain undermines the body's ability to regulate these stress hormones effectively. The hippocampus, pivotal for memory and stress regulation, often suffers damage from chronic stress. This results in a vicious cycle—with hormone levels rising and brain health deteriorating, increasing the risk of cognitive decline, which is particularly dreaded in aging. Despite these grim realities, the narrative doesn't suggest inevitability. Success in aging is possible, and many may navigate this journey without succumbing to the worst effects of stress. Understanding that some older adults manage to enjoy fulfilling, healthy lives highlights the potential for resilience and the need to focus on stress management strategies in later life. 4. Hope Amidst Challenges: The text concludes on an optimistic note, suggesting that while stress and aging intertwine to present formidable challenges, proactive coping mechanisms may provide substantial benefits. As the narrative transitions to exploring strategies for managing stress and the inherent individual differences in stress response, it hints at the promise of finding ways to mitigate the adverse effects of aging and enhance quality of life even in old age. Ultimately, while the chapter paints a vivid picture of the complexities surrounding aging and mortality, it encourages a reframed perspective that seeks both understanding and strategies for living successfully in later years. The hope is to shift focus toward methods of stress management that may brighten the aging experience, emphasizing that not all elements of aging must be fraught with despair.

Chapter 13 | WHY IS PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESS STRESSFUL?

In this chapter, Robert M. Sapolsky delves into the complexities of psychological stress and the physiological responses that arise from it. He argues that stress is not only a biological response but heavily influenced by psychological factors. Here's a detailed breakdown of the insights presented within this discussion. 1. The Intersection of Biology and Psychology: Sapolsky illustrates how various professional disciplines—such as bioengineering and psychology—have converged to enhance understanding of stress physiology. Bioengineers contributed significant clarity into how the body processes stress by mapping feedback systems related to glucocorticoid secretion, revealing that stress responses are sensitive and linear rather than all-or-nothing. 2. Psychological Modulation of Stress: A critical revelation of this research is that psychological factors can modulate the physiological stress response. For instance, experiments showed that an organism's ability to seek comfort can lead to a diminished stress response, highlighting the power of psychological appraisal in response to identical stressors. 3. The Role of Outlets for Frustration: Sapolsky discusses the importance of providing outlets for frustration, demonstrated through experiments with rats. The ability to express frustration—whether through physical activity, social interaction, or even imaginative distraction—can significantly reduce stress-related health risks, such as ulcers, in both animals and humans. This principle indicates that humans also benefit from hobbies, exercise, or social interaction as effective stress relievers. 4. The Impact of Social Support: Social connections play a crucial role in mitigating stress. Studies show that primates, including humans, experience reduced stress responses when they are supported by friends or family. Sapolsky notes that social support leads to lower glucocorticoid levels and can enhance overall health outcomes, suggesting that community and companionship are vital for managing stress. 5. Predictability and Control: Predictability is another factor that mitigates stress. When individuals know what to expect from a stressful situation, their stress response diminishes. For example, a warning that a stressor will happen can ease the burden of uncertainty. Control over stressors—often through belief rather than actual power—can also significantly affect stress levels. Individuals who feel they have control over their environment experience lower stress responses. 6. Perception of Improvement: The perception that circumstances are getting better can make stressors feel less daunting. Instances where people are aware that a risky situation is improving, even slightly, can help reduce the stress response. Conversely, perceived worsening of circumstances can amplify the stress reaction. 7. Interplay of Psychological Variables: Sapolsky emphasizes that psychological factors can intersect and potentially conflict with one another, creating complex stress experiences. For instance, while having control and predictability generally helps reduce stress, significant changes marked by a loss of predictability—even if positive—can still invoke stress. 8. Individual Differences in Stress Responses: Not everyone responds to stress in the same way, which is partly due to different psychological filters people apply to their experiences. Two individuals facing the same stressful situation may interpret it differently based on their past experiences, personality traits, and coping strategies. 9. Conclusion: Sapolsky summarizes the chapter by stressing that psychological variables are crucial in understanding stress responses. While biological factors undeniably contribute to susceptibility to stress-related diseases, the way individuals interpret and respond psychologically to stressors also plays a significant role. He suggests that identifying and harnessing these psychological levers can be pivotal in managing stress better in our lives. In his closing remarks, Sapolsky hints at exploring various psychiatric disorders in relation to stress perception, highlighting how this dynamic interplay impacts mental health and societal roles. This section presents a comprehensive exploration of the multifaceted nature of stress and offers a foundation for understanding how humans can adapt to or mitigate stressors in more profound ways.

Chapter 14 | STRESS AND DEPRESSION

Chapter 14 of "Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers" by Robert M. Sapolsky delves deeply into the intricate relationship between stress and major depression, highlighting the complexity of this mental illness and its biological underpinnings. The chapter opens by reflecting on society's fascination with exotic diseases, pointing out that while we are drawn to sensational stories, it is common conditions like major depression that are far more prevalent and damaging. From figures suggesting that 5 to 20 percent of the population will experience a major depressive episode in their lifetime, to predictions that it may become one of the leading causes of disability by 2020, the prevalence and severity of this condition are indisputable. 1. Major depression is characterized by distinct features that separate it from common feelings of sadness. Unlike everyday blues that may last temporarily, major depression must persist for at least two weeks and is often marked by severe incapacitation, an overwhelming sensation of grief, chronic guilt, and an inability to enjoy life—referred to as anhedonia, the lack of pleasure in activities once found enjoyable. 2. Depression manifests itself not merely as emotional distress but also physically. Symptoms can include significant alterations in sleep and appetite, cognitive distortions (where individuals maintain negative perceptions of themselves and their situations), and psychomotor retardation, which renders even simple tasks overwhelming. 3. The relationship between stress and depression is multifaceted. Stress acts not just as a predictor of depression but also as a trigger. Those who endure significant life stressors are more likely to develop depression, but interestingly, individuals who have experienced multiple depressive episodes may find that their depression becomes less dependent on external stressors over time, acquiring an internal rhythm. 4. Neurochemically, depression is associated with abnormalities in key neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine. Antidepressants often work by enhancing signaling of these neurotransmitters in the brain. However, the precise mechanisms remain complex, with ongoing debates about whether the core problem in depression is too little or too much of these chemicals. 5. Genetic factors also play a critical role in depression's onset and persistence. Family history significantly raises the risk of developing depression, suggesting a genetic vulnerability that is often compounded by environmental stressors. Recent findings have even pinpointed specific genetic variations that can elevate the risk for developing depression in response to stress. 6. The chapter also addresses the hormonal components of depression. Elevated glucocorticoids, produced in response to stress, can increasingly deplete neurotransmitter levels and impair brain function, exacerbating depressive symptoms. The relationship between hormone regulation and emotional regulation is highlighted, emphasizing the body’s systemic responses to stress. 7. Psychologically, theories of learned helplessness offer insights into how depression can develop. Experiments have demonstrated that individuals exposed to uncontrollable stressors often fail to cope effectively in subsequent situations, leading to a pervasive sense of helplessness akin to that experienced by depressed individuals. 8. The integration of stress research with psychological theory suggests that depression can result from a complex interplay between environmental stressors, biological predispositions, and maladaptive cognitive patterns. The understanding is that stress not only influences vulnerability to depression but also affects the biological systems in ways that can trigger or sustain the disorder. Overall, Sapolsky illustrates depression as a disorder that emanates from a converging of genetic, neurochemical, endocrine, and psychological factors. The impact of stress cannot be overstated, as it interacts with these elements to create a vulnerability that leads to depression in some individuals while allowing others to navigate life's challenges without succumbing to despair. Understanding this interplay is crucial for developing more effective treatments and nurturing resilience against the challenges posed by depression.

Key Point: Understanding the profound impact of stress on depression can inspire proactive mental health strategies.

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing at the crossroads of stress and emotional well-being; the realization that stress not only influences but can trigger major depression ignites a powerful motivation within you. As you move through your day-to-day life, you become acutely aware of stressors and their potential ripple effects on your mental health. This understanding empowers you to cultivate resilience through proactive strategies: perhaps prioritizing self-care, seeking therapy when needed, or fostering supportive relationships. Every choice becomes a conscious act of self-preservation. You learn to navigate life's complexities, not just surviving but thriving amid challenges. This perspective transforms your approach to stress, turning it into a more manageable force, equipping you with the tools needed to maintain your mental well-being and avoid the depths of despair.

Chapter 15 | PERSONALITY, TEMPERAMENT, AND THEIR STRESS-RELATED CONSEQUENCES

In Chapter 15 of "Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers," Robert Sapolsky delves into the intricate relationships between personality, temperament, and their consequent effects on stress and health. He begins by noting that while psychological factors can significantly modify stress responses, individuals vary in their capacity to manage these responses based on their inherent personality traits. 1. The impact of personality on stress response is illustrated through contrasting profiles of two individuals, Gary and Kenneth. Gary, despite outward success, remains perpetually stressed, leading to physiological issues such as elevated glucocorticoid levels, poor immune function, and a high risk of cardiovascular diseases. In contrast, Kenneth achieves a similar professional rank but adopts a more collaborative and relaxed approach, promoting healthy stress levels and enjoying a supportive social environment. This discrepancy highlights Richard Davidson's concept of "affective style," emphasizing how a person's attitude towards stressors can shape their overall health. 2. These profiles are not just human traits; they resonate with research conducted on primates, particularly baboons. Studies of baboon behavior indicate that individuals with higher social affiliation and better coping strategies tend to have lower stress markers, such as glucocorticoids. The study of baboons, living in a low-stress ecological context, underscores that social dynamics and coping behaviors significantly influence stress physiology. 3. Sapolsky further explores how personality styles manifest in both successful and maladaptive responses to stress. He identifies traits associated with better stress management, such as the ability to discern the nature of social interactions (threatening vs. benign), taking proactive control in stressful scenarios, and adapting well to feedback following social competition. Conversely, traits of insecurity and social isolation lead to chronic stress responses. 4. Personality types also extend into human psychiatric disorders, notably anxiety and depression. While anxious individuals often overreact in the face of potential threats, leading to heightened sympathetic nervous system activation, those with depression may exhibit prolonged peaks of glucocorticoids as a sign of giving up on coping strategies. The assertion here is clear: the way personality influences how one perceives, reacts to, and copes with stress can have profound psychological and physiological implications. 5. The discussion about Type A and Type B personalities plays a pivotal role in examining cardiovascular health. Early studies associated Type A traits—competitiveness, aggressiveness, and time urgency—with increased cardiovascular risk. However, newer findings indicate that hostility, rather than mere competitiveness, is the primary risk factor, as hostile individuals demonstrate excessive cardiovascular reactivity under stress. 6. The chapter further discusses the phenomenon of "repressive personality types"—individuals who consciously seem content but exhibit overactive stress responses. These people maintain a structured, rule-bound lifestyle, often leading to elevated glucocorticoids despite a lack of overt stress. The suppression of emotions and stringent self-control might generate an invisible yet significant physiological cost, manifesting as health issues in the long run. 7. Finally, Sapolsky emphasizes that the hidden burdens of personality types demonstrate that perceived stability and happiness might mask deeper stress-related vulnerabilities. The narrative thus intertwines scientific inquiry with personal reflections, urging a more nuanced understanding of how our temperamental differences shape our responses to life's inevitable stressors and ultimately affect our health trajectories.

Key Point: How personality affects stress responses

Critical Interpretation: Imagine yourself at a crucial juncture in your life—perhaps a big presentation or a personal challenge. You might find yourself feeling an overwhelming wave of anxiety, much like Gary, who, despite his achievements, remains ensnared in a web of stress. But what if instead, you could embody the temperament of Kenneth, approaching your hurdles with a sense of calm and collaboration? This chapter serves as a powerful reminder that your response to stress is not merely a reaction but an opportunity to choose your path. By fostering a more positive disposition towards challenges and prioritizing social connections, you can not only enhance your well-being but also improve your resilience. Embracing this insight could transform your life's interactions and outcomes, encouraging you to engage with stressors constructively rather than allowing them to undermine your health and happiness.

Chapter 16 | JUNKIES, ADRENALINE JUNKIES, AND PLEASURE

In exploring the intricate interplay between pleasure and stress, Robert Sapolsky delves into the fascinating and often paradoxical nature of human experiences, such as the inability to tickle oneself and the thrill of risk-taking. This chapter reveals several key findings about anticipation, dopamine release, and the dynamics of addiction in the context of stress. 1. Tickling and Surprise: The phenomenon of tickling oneself raises the question of predictability versus surprise. Research by Sarah-Jayne Blackmore indicates that the element of surprise is essential for the ticklish sensation. When people tickle themselves, they control the timing and location, eliminating surprise and thus the feeling of being tickled. However, if there’s a time delay or deviation from expected movements, the stimulus can still provoke a ticklish response, highlighting that unpredictability can lead to pleasure. 2. Pleasure Through Anticipation: Dopamine, a critical neurotransmitter involved in the brain's pleasure pathways, plays a significant role in how anticipation can be more pleasurable than the reward itself. When engaging in tasks, the anticipation of a reward triggers bursts of dopamine before the reward is received, emphasizing that pleasure is often rooted in expectation, not just fulfillment. This highlights the concept of the "appetitive" stage where desire fuels motivation to act and achieve a goal. 3. Paradox of Stress and Pleasure: Stress is typically viewed negatively, yet moderate and transient stress can enhance dopaminergic function and lead to heightened anticipation and enjoyment. Sapolsky points out that this balance between stress and pleasure can be context-dependent. Positive experiences are associated with manageable stress levels, while excessive stress leads to negative outcomes. The thrill of activities that involve risk, like bungee jumping, can be pleasurable precisely because they momentarily strip away control in a safe environment. 4. Addiction Mechanics: Sapolsky explores the neurochemistry of addiction, noting that many addictive substances stimulate release of dopamine in the pleasure pathways. Over time, these substances can lead to tolerance, requiring greater amounts for the same effect. Interestingly, the transition from "wanting" to "needing" a substance reveals that cravings often surpass the original pleasure experienced. Stress and trauma also heighten the susceptibility to addiction, as stress responses can prime the brain for greater reward-seeking behavior. 5. Context-Dependent Relapse: The chapter examines how context influences relapse in those recovering from addiction. Specific environments associated with previous drug use can reignite cravings, regardless of the time elapsed since stopping drug use. This learning process emphasizes the importance of environmental cues in sustaining addiction. 6. Role of Early Stress in Addiction Vulnerability: Experiences of stress during critical developmental periods can predispose individuals to later addiction. The chapter captures how stress during childhood shapes the sensitivity of reward pathways, making such individuals more likely to seek out substances as adults. 7. Negative Affect and Self-Medication: Addictive behaviors can serve dual functions—providing both pleasure and relief from negative emotions. This signal to engage in substance use can be amplified in stressful environments. Sapolsky suggests that a lack of healthy opportunities for pleasure in modern society may push individuals toward addictive behaviors as a coping mechanism. 8. Synthetic Pleasures and Modern Desires: The chapter also critiques the way contemporary society offers pleasures that are overly intense and quickly habituated. This conditioning can dull the appreciation for subtle joys in life, creating a cycle where individuals seek larger and more immediate gratifications, ultimately becoming dissatisfied with their experiences. In summary, Sapolsky highlights the complex relationship between stress, anticipation, pleasure, and addiction, suggesting that our understanding of happiness needs to reconcile with our capacity for stress. The patterns of seeking pleasure amid stress reveal deeper truths about human nature and the context in which we experience life’s challenges and rewards.

Chapter 17 | THE VIEW FROM THE BOTTOM