Last updated on 2025/04/30

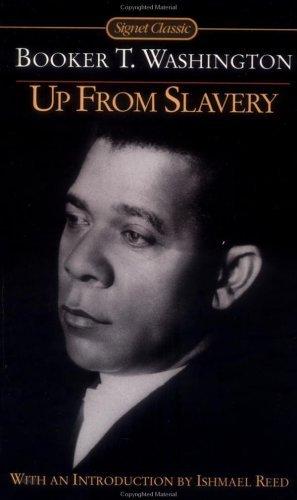

Up From Slavery Summary

Booker T. Washington

Empowerment through Education and Self-Reliance for Freedom.

Last updated on 2025/04/30

Up From Slavery Summary

Booker T. Washington

Empowerment through Education and Self-Reliance for Freedom.

Description

How many pages in Up From Slavery?

332 pages

What is the release date for Up From Slavery?

"Up from Slavery" by Booker T. Washington is a powerful autobiographical narrative that chronicles the author's journey from the shackles of bondage to the heights of educational and vocational achievement, embodying the struggle for dignity and empowerment within the African American community in the post-Civil War era. Washington's poignant reflections not only illuminate the harsh realities of racism, poverty, and inequity but also present a hopeful blueprint for self-improvement through hard work, education, and industrial training. His philosophy of self-reliance and focus on practical skills as a pathway to social advancement resonate deeply, inviting readers to explore the transformative power of perseverance and dignity in the face of overwhelming adversity. Through his compelling life story, Washington inspires us to recognize the value of resilience and the pursuit of knowledge as essential tools for personal and collective liberation.

Author Booker T. Washington

Booker T. Washington was a prominent African American educator, author, and orator who played a pivotal role in the post-Civil War era of race relations in the United States. Born into slavery in 1856 in Virginia, Washington rose to prominence by founding the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, which became a leading institution for vocational education aimed at empowering African Americans through skill development. His philosophy, often referred to as accommodationism, emphasized the importance of economic self-reliance and gradual social integration rather than immediate civil rights advocacy. Washington's influential writings, particularly in his autobiography "Up from Slavery," offered insights into the struggles and aspirations of African Americans during a time of significant societal change, and he remains a key figure in discussions of race and education in America.

Up From Slavery Summary |Free PDF Download

Up From Slavery

Chapter 1 | A SLAVE AMONG SLAVES

Booker T. Washington begins his autobiography, "Up from Slavery," with a poignant reflection on his early life as a slave, highlighting the harsh realities and struggles faced by himself and his family in the antebellum South. His narrative is structured around various themes and principles that illuminate the complexities of slavery, human relationships, and the pursuit of freedom. 1. The Humble Beginnings of a Slave: Washington recounts that he was born around 1858 or 1859 on a plantation in Franklin County, Virginia. Lacking precise details regarding his birth, he offers a glimpse into his childhood home—a small log cabin where he lived with his mother and siblings in the slave quarters. He emphasizes the dreary atmosphere of his surroundings, not necessarily due to cruel owners, but due to the overall dismal state of slavery. 2. Ancestral Roots and the Nature of Slavery: Washington reflects on the absence of knowledge about his ancestry, a common issue among slaves due to the fragmented nature of family records under slavery. He speaks briefly about his mother and the hardships endured by those transported from Africa, acknowledging the pain and trauma of his heritage while recognizing that his personal circumstances were reflective of the broader experiences of countless enslaved individuals. 3. Daily Life and Hardships: Life in the cabin was filled with difficulties; it lacked basic comforts such as glass windows and wooden floors. His mother had the dual role of caretaker and plantation cook, and Washington recalls the instances where they secured food—often with a mother's desperate ingenuity. The narrative reveals a lack of play and leisure during his early years as he was tasked with labor instead. 4. Education and Awareness of Freedom: Although Washington received no formal education as a slave, he expresses a deep yearning for knowledge, which he glimpsed while accompanying his young mistress to school. He describes the moment he became aware of their status as slaves and the discussion surrounding Lincoln’s efforts to address slavery, illustrating how even in the depths of their oppression, many enslaved individuals were acutely aware of the larger socio-political climate. 5. A Complex Relationship with Former Owners: Washington notes the nuanced feelings that enslaved individuals had towards their owners, marked not by hatred but often by sorrow, especially during the Civil War. He mentions how slaves experienced genuine grief for the suffering of their masters, revealing a depth of humanity and loyalty that complicates the narrative surrounding slavery. 6. The Burden of Freedom: When the moment of emancipation arrived, Washington describes the rush of emotions among the slaves. Initially filled with joy and relief, the reality of freedom soon transformed into a profound sense of responsibility and uncertainty. Many were confronted with the daunting task of building their lives anew without guidance or resources. The elation of freedom was swiftly overshadowed by the harsh realities of self-sufficiency, which many felt unprepared to navigate. 7. The Legacy of Slavery and Personal Responsibility: Washington emphasizes that freedom is not merely a gift granted but a responsibility that requires careful thought and action. He asserts a belief in the resilience of his people, highlighting their ability to navigate the trials of freedom despite the deep attachments formed during their years of servitude. Through his reflections, Washington offers a compelling narrative that interweaves personal memory with the historical context of slavery, expressing both the pain of subjugation and the hope rooted in the promise of freedom. His story becomes not just an account of suffering, but also one of aspiration, resilience, and the enduring quest for dignity and self-determination.

Chapter 2 | BOYHOOD DAYS

In the second chapter of "Up from Slavery," Booker T. Washington reflects on the transformative period following emancipation. The chapter opens with a common sentiment shared among freed African Americans: the need to change their names and leave their old plantations to truly experience their newfound freedom. Upon liberation, many felt it improper to retain the surnames of their former owners, resulting in a wave of new names that symbolized their independence. This act of renaming became a powerful declaration of their status as free individuals, contrasting their past when they were often only referred to by a first name or as "property" of their white owners. Washington recounts his family's journey from Virginia to West Virginia, prompted by the desire for freedom and better opportunities. His mother’s husband had found work in a salt mine and arranged for them to join him, setting off on a long and arduous trek with limited possessions. The journey was marked by hardship, including a memorable encounter with a snake in an abandoned cabin that prompted them to continue on their way. Eventually, they arrived in Malden, a town thriving on the salt industry, where Washington's stepfather had secured a job and housing. Despite the challenging living conditions and the presence of degraded environments, Washington's ambition for education flourished even in such trying circumstances. Working in a salt furnace from an early age, Washington experienced the harsh realities of labor while yearning for knowledge. He first learned to recognize the numeral assigned to his family and developed a hunger for reading that would shape his future. When he managed to acquire a spelling book, he took great strides toward education, motivated by a thirst for knowledge that could elevate his circumstances. His mother, though uneducated herself, supported his endeavors and encouraged his desire to learn. The presence of a well-educated boy from Ohio sparked a collective aspiration within the community to establish a school for colored children in the area. The initial discussions generated immense excitement, highlighting their desire for education—a longing that transcended age and background. Washington poignantly notes the eagerness among all members of his race to learn, showcasing a profound commitment to education that punctuated the African American experience during this transformative time. However, Washington’s ambitions encountered roadblocks; despite his desire to attend school, he was required to work longer hours in the salt mines. This setback was frustrating, particularly when witnessing peers heading off to school. Undeterred, he sought night classes, leveraging every opportunity to learn despite the limitations imposed by his circumstances. This tenacity foreshadowed Washington's later work in education as he drew on his own experiences in both day and night schools. His struggles with personal appearance and identity also emerged as themes in this chapter. Washington recounts feeling inadequate without proper clothing when he noticed other children wearing hats. His mother's resourcefulness in crafting a cap for him became a lesson in humility and self-reliance, instilling in him values that transcended material possessions. This sentiment resonated deeply with Washington, as he learned the importance of authenticity and pride in one's circumstances. As he navigated the educational landscape, Washington also reflected on the implications of his name—initially known simply as "Booker." Pressured to conform to the norms of his peers who possessed additional surnames, he chose to adopt "Washington," a decision symbolizing both personal agency and a recognition of his heritage. Later in life, he would uncover his full name, "Booker Taliaferro Washington," but the act of naming himself was a noteworthy milestone in his journey towards establishing an identity parallel to dignity and self-respect. Throughout his childhood, Washington faced numerous challenges and obstacles, creating an awareness of the societal differences shaped by race. He recognized that the expectations placed upon African American youth contrasted starkly with those placed upon white youth, who were afforded presumption of success. However, he began to view these challenges as sources of strength, asserting that through struggle comes the resilience necessary for true achievement. In reflecting on his upbringing, Washington expressed gratitude for his identity, asserting that the lack of an esteemed lineage motivated him to forge a path of integrity and worth. He challenged societal prejudices, minimizing the notion that ancestry solely dictates one’s potential for success, emphasizing that intrinsic merit ultimately prevails over mere lineage. In continuing to persevere through challenges, Washington found pride in his race and resolved to establish a legacy of meaningful contribution to humanity—a sentiment rooted in education, dignity, and self-empowerment that would shape his life's work.

Chapter 3 | THE STRUGGLE FOR AN EDUCATION

In his autobiographical account in "Up from Slavery," Booker T. Washington recounts the transformative journey he undertook in pursuit of education, shedding light on both personal aspirations and broader societal challenges faced by African Americans in the post-Civil War era. His story begins in the confines of a coal mine, where he overhears two miners discussing the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute—a school that promised opportunities for young Black individuals to gain an education while working to cover their costs. This revelation ignites a fierce determination within Washington to attend Hampton, despite knowing little about its location or the expenses involved. To realize his dream, Washington navigates a series of challenges, beginning with his transition from the coal mine to working for General Lewis Ruffner and his wife, Mrs. Viola Ruffner, who is noted for her strict discipline. In her home, he learns valuable life skills such as cleanliness, organization, and the importance of honesty. His time with Mrs. Ruffner proves to be as instrumental as formal education, providing him with a foundation of discipline and values that would serve him well in his future endeavors. 1. Washington's aspiration to attend Hampton is met with skepticism, particularly from his mother, who fears he is embarking on a futile quest. Undeterred, he embarks on a journey fraught with financial limitations. Washington begins with only a small amount of money—often relying on the kindness of his community, who provide him with small donations as they support his education initiative. 2. The traveling experience itself is a testament to the racial barriers of the time; Washington's first encounter with overt racism occurs when he is denied room and board at a hotel solely on account of his skin color. Despite facing harsh realities, this experience fuels his resolve to reach Hampton. 3. Upon finally arriving in Richmond, Washington faces further uncertainty, having to find work to support his education. He takes on labor aboard a ship, which proves beneficial as it provides him with enough money to buy food. Even amidst hunger and tiredness, Washington remains focused on his goal—enhanced by the realization that each struggle contributes to his growth and determination. 4. After saving enough for the final leg of his journey, Washington arrives at Hampton with a mere fifty cents to his name. His first impressions of the institution are profound; the imposing school building symbolizes hope and opportunity, inspiring him to dedicate himself fully to his studies. 5. To gain admission, Washington impresses the head teacher by demonstrating his strong work ethic through a simple act of sweeping a classroom to perfection. This reveals his belief in the value of hard work, which is further recognized when he is offered a position as a janitor, allowing him to work off the cost of his board. 6. Throughout his experience, Washington reflects on the significant influence of General Samuel C. Armstrong, the head of Hampton, who embodies the spirit of selfless leadership and dedication to the upliftment of African Americans. Armstrong’s presence and guidance shape Washington’s educational journey, instilling in him a commitment to serve his community. 7. Life at Hampton brings many lessons beyond academics. Washington learns the value of routine, personal hygiene, and respectability, which he acknowledges were largely unfamiliar to him before arriving. He shares insights into the communal struggles of his fellow students, emphasizing their collective desire to uplift their communities through education. 8. Washington notes the hard work and dedication of his instructors—primarily Northern white teachers—who strive tirelessly for the betterment of their students. He emphasizes the historical significance of their contributions in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, asserting that their efforts deserve acknowledgment and appreciation. In conclusion, Washington's narrative encapsulates the immense obstacles faced by individuals seeking education in a racially divided America. His story highlights the integral role of personal determination, community support, and the transformative power of education in overcoming adversity. As he navigates the corridors of Hampton and learns from both its faculty and fellow students, Washington emerges not only with an education but also with a profound understanding of his role in advocating for and uplifting his race.

Key Point: The transformative power of education and hard work

Critical Interpretation: Booker T. Washington's relentless pursuit of education, despite facing numerous hardships, serves as an uplifting reminder that your own aspirations can be reached through determination and hard work. As you navigate your life’s challenges, remember that each obstacle is a stepping stone to growth. Much like Washington, who found purpose in every task, from sweeping classrooms to working on ships, you too can transform your experiences—no matter how daunting—into opportunities for personal development and community upliftment. Embrace the lessons that come from perseverance in the face of adversity, and let education be your tool for change, not just for yourself, but for those around you.

Chapter 4 | HELPING OTHERS

At the close of his first year at Hampton Institute, Booker T. Washington faced unforeseen adversity, unable to afford a return home while his fellow students departed for vacation. While feeling despondent and homesick, he devised a plan to sell a second-hand coat to cover travel expenses. Unfortunately, the buyer could only offer him five cents upfront, leading Washington to abandon hopes of leaving Hampton for work. His quest for employment culminated in a restaurant job at Fortress Monroe, where his meager wages were primarily consumed by board. However, he utilized this time for personal growth and study, reaffirming his ambition to repay a $16 debt to Hampton, which he viewed as an obligation of honor. Washington’s fortunes momentarily brightened when he discovered a ten-dollar bill under a restaurant table, only to see it claimed by the proprietor. Despite this setback, he approached General J.F.B. Marshall, the treasurer, to discuss his financial situation. Marshall’s trust allowed Washington to reenter Hampton, where he worked as a janitor during his second year. It was here that he learned invaluable lessons about selflessness and the dignity of labor, largely influenced by the unyielding dedication of his teachers. One of the most transformative experiences for Washington at Hampton was his introduction to the Bible, through which he found both spiritual nourishment and literary appreciation. The enthusiasm of Miss Nathalie Lord sparked his love for public speaking, as she provided him with private lessons to enhance his communication skills. His involvement in debate societies solidified his interest in effective expression and advocacy. Returning home after two years at Hampton, Washington encountered further obstacles due to a miners’ strike that left him unable to find work. Tragically, he received the news of his mother’s death while seeking employment. Devastated, he soon faced chaos at home, but the kindness of a close friend facilitated his return to work and stability. Despite difficulties, Washington's determination to return to Hampton never wavered. He took on cleaning duties before the start of the new term, reinforcing his belief in labor’s transformative power. Throughout his final year, Washington dedicated himself to academics and achieved recognition among his peers. After graduation, his first experience as a waiter presented challenges, but he persevered and eventually excelled at the role. With this newfound experience, he returned home to teach at a colored school, viewing the role as a vital opportunity to uplift his community by providing not just academic instruction but guidance in personal hygiene and dignity. Alongside his teaching responsibilities, Washington established night schools to accommodate working individuals seeking education, indicating his commitment to serving those eager for knowledge. Despite external challenges, including the era of the Ku Klux Klan, Washington remained focused on his mission to uplift his people, highlighting a stark contrast between past injustices and the progress he believed was possible for African Americans. Through persistence, service, and the insights gained from his own struggles, Booker T. Washington crystallized the notion that true fulfillment comes from helping others, a principle that continued to define his life's work. This period marked not only his personal growth but also his dedication to the advancement of his community and the empowerment of his race.

Chapter 5 | THE RECONSTRUCTION PERIOD

During the Reconstruction period from 1867 to 1878, significant changes unfolded for the African American community, a time marked by educational aspirations and evolving social structures. The era, spanning Booker T. Washington's experiences as a student and teacher, reveals two predominant ideas among African Americans: a fervent pursuit of classical education, particularly in Greek and Latin, and a strong desire for political office. 1. Educational Aspirations and Misconceptions: After generations of slavery, the newly freed African Americans sought education with great enthusiasm. Schools across the South, often bursting at the seams with students of all ages, exemplified this quest. However, there was a prevalent misunderstanding that acquiring education would automatically shield individuals from life’s difficulties and manual labor. This misplaced belief often led to the assumption that learning classical languages would confer an elite status, bordering on the extraordinary. 2. The Teaching and Ministry Professions: Many educated African Americans transitioned into teaching or preaching roles. While some exhibited real competence and sincerity, a substantial number gravitated towards these professions merely as an easy source of income. Instances of poorly qualified teachers were not uncommon; one contender for a position could not even affirm whether the earth was flat or round. The ministry, in particular, suffered from a plethora of ineffective and sometimes immoral individuals claiming a divine calling, with many new ministers emerging with scant education or moral integrity. 3. Political Aspirations and Challenges: The Reconstruction era also saw African Americans looking to the Federal Government for support, much like children depend on their parents. Though the government granted freedom, Washington critiqued its failure to ensure African Americans received adequate educational provisions for informed citizenship. He expressed concern over the exploitation of his community’s ignorance to further political ambitions of some Northern whites, positing that this would harm their social fabric rather than advance it. 4. The Need for Practical Skills: Despite the temptations of political engagement, Washington felt the most effective way to uplift his community lay in the practical training of skills suited for honest, hard work. He observed a number of African American officials whose lack of education and moral grounding resulted in detrimental governance. He noted that while some individuals held significant offices, many were unqualified, emphasizing that education must be married with industriousness and self-reliance. 5. Comparative Educational Experiences: After two years of teaching in Malden, Washington spent eight months studying in Washington, D.C., where he contrasted institutions that emphasized rigorous industrial training, like Hampton Institute, with those that focused on classical education. The former nurtured self-reliance and practical skills, while the latter often produced individuals more concerned with outward appearances and less equipped to address real-world challenges. 6. Social Observations and Economic Realities: Washington's observations of the African American community in Washington revealed a troubling superficiality among some individuals, who, despite meager incomes, engaged in ostentatious displays to project wealth. He noted a reliance on federal positions and an alarming lack of ambition among certain groups, fostering a culture of dependence rather than self-sufficiency. 7. Consequences of Education Without Practical Skills: Washington pointed out the impact of education that did not align with marketable skills. Young women, encouraged to rise above their mothers' occupations in laundering without sustainable job prospects, faced dire consequences when their aspirations exceeded their realities. He advocated for an educational balance that combined academic enrichment with practical training in traditional trades to foster both professional and personal development. Washington's reflections on the Reconstruction period underscore the complexities faced by African Americans as they navigated their newfound freedom. His insights emphasized the need for a balanced approach to education — one that nurtured both intellect and practical skills — as a cornerstone for the community's progress and integration into society.

Key Point: The Need for Practical Skills

Critical Interpretation: The journey through life is often filled with challenges and uncertainties, and as you strive for your goals, it’s vital to remember that education without practical application can lead you astray. Like Booker T. Washington, who recognized the importance of combining intellectual growth with tangible skills, you too can draw inspiration from this. By bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and hands-on experience, you empower yourself to tackle real-world problems with confidence. Whether it’s learning a trade, honing a craft, or developing entrepreneurial skills, remember that practical training not only provides you with financial independence but also shapes your character and fortifies your resilience, guiding you toward success in every endeavor you pursue.

Chapter 6 | BLACK RACE AND RED RACE

During my time in Washington, there was significant discussion in West Virginia regarding the relocation of the state capital from Wheeling to a more central location. Consequently, the Legislature identified three cities, with Charleston being just five miles from my home, for a public vote. After accepting an invitation from a committee in Charleston, I spent three months advocating for the city, which ultimately won the vote and became the capital. 1. Educational Priorities Over Political Aspirations: Although many young men and women of my race aimed to pursue careers as lawyers or musicians, I believed our community needed a stronger foundation in education, industry, and property ownership. My desire was to contribute to the collective good rather than seek individual political success. Following my campaign, I received an unexpected invitation from General Armstrong to deliver the post-graduate address at Hampton's Commencement, an honor I earnestly prepared for. During this time, I reflected on how much had changed in my life since my first journey to Hampton, emphasizing the growth of both the institute and myself. 2. Adapting Education to Community Needs: Upon my return to Hampton, I noticed that the institute had evolved remarkably under General Armstrong’s leadership, tailoring its curriculum to meet the specific needs of our people rather than adhering to outdated educational models. After my successful address, General Armstrong invited me back to Hampton as a teacher while I pursued further studies. I had previously guided promising students to the institute, leading to my return as an instructor. 3. The Challenge of Educating Native Americans: At this time, Armstrong initiated a groundbreaking project to educate Native American youths at Hampton, and he appointed me to oversee these students as a "house father," managing their living arrangements and discipline. Although I was apprehensive about this role, I embraced the responsibility and quickly earned their trust and respect. The transition proved mutually beneficial as the Native American students and the African American students formed a supportive community, showcasing the power of kindness and collaboration across racial lines. 4. The Significance of Kindness and Community: The willingness of the colored students to assist the Indian students in their adaptation illustrated a profound understanding of our shared experiences with prejudice and discrimination. There was an innate desire among students to uplift one another, reflecting an expansive and compassionate spirit. 5. Classroom Experiences Reflecting Societal Predicaments: My encounters in public life sometimes highlighted the absurd nature of racial classifications. Instances of mistaken racial identity exposed the arbitrary and often ridiculous barriers imposed by society. These experiences highlighted the importance of dignity in human interactions, regardless of one's background. 6. The Birth of the Night School: As the year progressed, Armstrong recognized the need for a night school for impoverished young people who wished to gain an education. I eagerly took charge of this initiative, teaching earnest students who worked diligently during the day. Their commitment led to the establishment of a program that would eventually evolve into a vital aspect of the institution. This program drastically expanded from twelve to twenty-five students, later growing to hundreds, reflecting the enduring value of education for young men and women eager to improve their lives. My teaching experiences during this time lived up to their reputation; I often referred to my students as "The Plucky Class" due to their exceptional determination and hard work. Their journey inspired me and others, demonstrating that the desire for education and self-improvement knows no bounds when coupled with commitment and resilience.

Key Point: The Power of Education and Community Support

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing in a room filled with eager faces, each one reflecting determination and hope. Just like the students in Booker T. Washington’s night school, you, too, can harness the incredible force of education to uplift not only yourself but also those around you. This chapter serves as a radiant reminder that by prioritizing learning and fostering a supportive community, you can break through barriers and create pathways for growth—both personally and collectively. Embrace this transformative power, take a step towards knowledge, and watch how your commitment to education can inspire others to rise alongside you, creating a ripple effect of empowerment and resilience.

Chapter 7 | EARLY DAYS AT TUSKEGEE

In Chapter 7 of "Up from Slavery," Booker T. Washington chronicles his initial experiences and challenges during his early days at Tuskegee. This period marks the beginning of his significant life work in education for African Americans. 1. After teaching night classes at Hampton Institute under the mentorship of Rev. Dr. H.B. Frissell, Washington received an unexpected opportunity in May 1881 wherein General Armstrong suggested he lead a new normal school in Tuskegee, Alabama. This move was particularly significant as the expecting gentlemen had presumed no qualified Black candidate was available, reflecting prevailing racial attitudes. Washington's willingness to accept the position initiated his profound journey. 2. Upon arriving in Tuskegee—a town with a sizable Black population and a history of education for white citizens—Washington discovered there were no infrastructures for the school. However, he found an eager and motivated community, thirsty for education. The term "Black Belt," which described the area’s rich soil conducive to cotton cultivation during slavery, also represented areas where Black individuals outnumbered whites, signifying a particular socio-political dynamic. 3. Washington faced many logistical challenges, as the only funding available was a small state appropriation for teacher salaries, leaving him with immense responsibility to build the school from the ground up. The reality was stark; he had to secure a dilapidated building for classes, often teaching under conditions that required students to hold umbrellas over him during rain. The initial struggle revealed the deep commitment among the local Black community eager to support and participate in the educational endeavor. 4. In his observations of the local community, Washington noted the stark realities of their living conditions, where families shared cramped quarters with limited amenities. He experienced firsthand their resilience but also their struggles, observing their dietary habits, often limited to corn bread and fat pork, and the peculiarities of their consumption choices alongside vestiges of consumerism, such as costly sewing machines and organs. 5. Washington traveled extensively in Alabama during his first month, immersing himself in the lives of the people. He documented the daily life, the familial breakdown of roles in the cotton fields, and the socio-economic challenges they faced, such as debt and the lack of proper schoolhouses. This grassroots engagement allowed him to witness authentic everyday experiences that were vital for shaping his educational strategies. 6. Despite these hardships, Washington also encountered encouraging instances of community and educational aspiration. He recognized that the dire situations he reported were not universal and were somewhat alleviated by the very educational initiatives he planned to implement. He remained optimistic about the potential for transformation through education. In conclusion, Washington's early days at Tuskegee were marked by both overwhelming challenges and deep community spirit. His commitment to education in the heart of Alabama laid the groundwork for transformative changes in the lives of African Americans, creating a legacy that would resonate through generations. This chapter not only captures Washington's personal journey but also reflects the broader struggle for racial and educational equity in post-Emancipation America.

Chapter 8 | TEACHING SCHOOL IN A STABLE AND A HEN-HOUSE

Booker T. Washington reflects on his experiences during a month of travel to understand the realities faced by African Americans in the South. His observations left him disheartened, revealing the immense challenges ahead to uplift this community. Nevertheless, he recognized that merely replicating the New England educational model would not suffice to address their specific needs. Instead, he saw value in the innovative educational practices established by General Armstrong at Hampton Institute. Washington planned to inaugurate a school in Tuskegee on July 4, 1881, with the commitment of local citizens, both white and colored, rallying support despite some opposition. Many white residents harbored concerns about the educational initiative, fearing it would devalue African American labor and foster racial tensions. Two crucial figures emerged in support of Washington's efforts: Mr. George W. Campbell, a white ex-slaveholder, and Mr. Lewis Adams, a black ex-slave. Both recognized and believed in Washington’s educational vision, offering invaluable guidance and financial assistance. Their diverse backgrounds reflected the complex interplay of race and education during this transformative era. When the school opened, thirty eager students arrived, mostly public-school teachers above the age of fifteen. Washington quickly observed that their knowledge was surface-level, focusing on memorization rather than practical application. Many students seemed to aspire to an education that would free them from manual labor rather than empower them with skills and knowledge to uplift their communities. The school saw increased enrollment, but Washington recognized that teaching merely academic subjects was inadequate. He and Miss Olivia A. Davidson, who later became his wife and co-teacher, sought to establish a curriculum that emphasized both practical life skills and trade knowledge alongside academic subjects. Despite limited resources—operating out of makeshift facilities like a stable and a henhouse—Washington and his students embraced hands-on learning and actively participated in agricultural projects. This model was meant to ensure that the education they received aligned with their socio-economic realities, preserving a connection to agricultural traditions and the land. Faced with financial challenges, Washington successfully negotiated a loan to purchase an abandoned plantation, which offered the possibility of stability and growth for the Tuskegee Institute. Fundraising initiatives led by Miss Davidson involved community festivals, drawing support from both white and black residents. Their combined efforts demonstrated a strong commitment to the education of the African American community. Notably, Washington recounts a poignant moment when an elderly woman contributed six eggs, symbolizing the sacrifices made by many who had lived through slavery, emphasizing their investment in future generations. This experience highlighted the deep-seated desire for education and improvement within the African American community, reinforcing the mission of Tuskegee Institute as a means of elevating both individuals and the broader society.

Key Point: The importance of practical education and community support.

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing alongside Booker T. Washington as he creates the Tuskegee Institute, a beacon of hope amidst adversity. In this chapter, you're reminded of the transformative power that education, grounded in real-world skills, can wield in uplifting your community. It inspires you to seek knowledge that is applicable, urging you to intertwine your aspirations with practical actions. You begin to understand that education is not merely about acquiring degrees but about fostering a spirit of collaboration and resilience. As you navigate your own challenges, this ethos fuels your determination to not only learn but to give back, engaging with your community and empowering others through shared experiences and resources. This realization ignites a passion within you to embody the same spirit of innovation and collectivity—ensuring that every lesson learned is a stepping stone toward a better tomorrow for everyone around you.

Chapter 9 | ANXIOUS DAYS AND SLEEPLESS NIGHTS

The arrival of Christmas in Booker T. Washington's first year in Alabama offered profound insights into the life of the local community, particularly among the African American population. Early morning visits from eager children asking for Christmas gifts reflected a tradition rooted in a history that granted people time off during the holiday season, a practice that dated back to the days of slavery. However, this joyous season was often marred by excessive drinking and revelry, diminishing the true meaning of Christmas. Washington observed the stark poverty faced by many families, finding their celebrations limited to minor treats—firecrackers, ginger-cakes, and in some cases, alcohol—rather than the spiritual significance of the occasion. During this Christmas season, Washington visited families on local plantations, noting their struggles to derive joy from a time that many celebrate with love and reverence. His interactions highlighted a prevalent culture that, while attempting to celebrate, often led to chaotic gatherings fueled by alcohol, neglecting the sacredness of the holiday. In contrast, Washington's school at Tuskegee made a concerted effort to instill a deeper understanding of Christmas in its students by promoting a more meaningful observance of the season. This shift helped graduates develop a sense of community service, supporting those less fortunate and fostering a spirit of giving. 1. Community Collaboration: Washington recognized the importance of integrating the school into the local context. He aimed to cultivate relationships with both white and black community members, which he believed would lead to mutual support and investment in Tuskegee. This approach proved effective, as notable support from local white citizens began to emerge, thus erasing some barriers and fostering goodwill. 2. Financial Challenges and Development: The school faced ongoing financial strains, yet perseverance led to securing funds necessary for expansion, allowing for the purchase of land and subsequent establishment of agricultural practices. Beginning with humble resources, the school quickly grew through community effort and contributions, showing that unity and shared purpose could overcome hardship. Notably, a white mill owner demonstrated trust by providing lumber for the new school building without immediate payment guarantees. 3. Community Engagement and Fundraising: Washington observed an ambitious spirit within the community, where individuals contributed not just money but also personal resources, including livestock, for the school's development. This grassroots support was vital, leading to both financial assistance and volunteer labor for constructing facilities. 4. Support from the North: Washington's wife, Miss Davidson, played a crucial role in extending efforts beyond the Southern community, garnering support from Northern benefactors. Her personal dedication to fundraising and building relationships reinforced the school’s mission, leading to critical financial contributions and support from various individuals and organizations. 5. Foundation of Values Through Hardship: Washington faced countless sleepless nights worrying about the sustainability of the school amidst financial uncertainty. Yet, during these tumultuous times, he remained committed to maintaining the school's credit and reputation. The collaboration and support he garnered exemplified a larger principle that financial integrity and community trust were vital for the institution's survival. 6. Personal Trials: The chapter culminated in Washington's personal life, as he married Miss Fannie N. Smith, sharing in the dream of Tuskegee’s success, only to experience deep loss when she passed away shortly after. Their union symbolized a partnership committed to education and progress, and though brief, her support was pivotal in the foundational years of the school. In conclusion, Washington's reflections during this period underline the intertwined nature of community, hardship, and the pursuit of education. His experiences captured a pivotal moment in American history where the potential for growth and collaboration existed, despite the prevailing challenges of poverty and racial inequity. The commitment to uplift oneself and one’s community persisted amid struggles, demonstrating resilience and hope for future generations.

Chapter 10 | A HARDER TASK THAN MAKING BRICKS WITHOUT STRAW

In Chapter 10 of "Up from Slavery," Booker T. Washington reflects on the challenges faced at the Tuskegee Institute, focusing on the philosophy of practical education through self-reliance and industriousness. Washington emphasizes the importance of teaching students to not only engage in agricultural and domestic tasks but also to contribute to the construction of their own school buildings. His goal was to instill in them a sense of dignity and love for work, elevating labor beyond mere drudgery. 1. Educational Philosophy: Washington's mission was rooted in the belief that practical education would empower students. He sought to show them how to harness nature's forces—like air, water, and steam—to improve their work processes. Many skeptics questioned this hands-on approach, believing that it would result in inferior facilities. However, Washington remained steadfast, knowing that the lessons learned from self-reliance would outweigh any initial discomfort. 2. Building by Hand: Over nineteen years, students at Tuskegee built multiple structures using their labor, marking a significant achievement in self-help and community engagement. Washington narrated that despite initial setbacks, including the failure of multiple brick kilns, perseverance led to competence in brickmaking. The school's success in this industry instilled skills in students that spread throughout the South, leading to economic independence for many. 3. Community Relations: The brickmaking endeavor not only provided material needs but also fostered goodwill between races. Through the sale of quality bricks, Tuskegee created a commercial link with the local community, challenging prejudices and demonstrating the value of education for African Americans. Relationships formed through mutual economic interest played a crucial role in promoting peace and cooperation. 4. Facing Challenges: Washington shares personal trials, such as the struggle for funding and the unpopularity of manual labor among students. Despite opposition from parents who preferred a purely academic curriculum, Washington continued to advocate for industrial education, believing that hands-on experience would ultimately yield more significant results. 5. Gradual Development: The establishment of a boarding department marked another key development at Tuskegee. With very few resources, Washington and the students tackled the complex task of creating a dining facility. Their resourcefulness—transforming a basement into a kitchen and dining area—set the tone for a pragmatic approach to problem-solving that characterized the school. 6. Long-Term Vision: Washington reflected positively on the hardships faced during those early days. He felt that starting in a humble setting fostered resilience and grounded the institution in reality, allowing it to grow organically. As he observed later successes, including a thriving dining hall, he appreciated the long journey of development and the character it built in the students. In closing, Washington's narrative in this chapter encapsulates his vision of education as a vehicle for self-improvement and social progress, highlighting the enduring value of hard work, resilience, and community engagement. Through perseverance, Tuskegee became not just a school, but a powerful symbol of empowerment and progress for African Americans.

Key Point: The Value of Self-Reliance through Practical Education

Critical Interpretation: Imagine stepping into the world with the understanding that your hands can create change, just as they did for Washington's students at Tuskegee. The lesson here is profound: by engaging in practical education and embracing self-reliance, you cultivate a spirit of industriousness that empowers you not only to meet life's challenges but to transform them into opportunities. Picture yourself building something from the ground up, whether it's a project, a skill, or even a career—this process instills a sense of dignity and fulfillment in your work. Just as those students learned to construct their own school, you too can construct your destiny, channeling perseverance and hard-earned skills into a life full of purpose and achievement. In choosing to embrace the value of labor, you forge not just forward momentum in your own life, but also contribute to the growth of your community and inspire others along the way.

Chapter 11 | MAKING THEIR BEDS BEFORE THEY COULD LIE ON THEM

In this chapter from "Up from Slavery," Booker T. Washington recounts significant developments at Tuskegee Institute, highlighting the interactions with supporters from Hampton Institute, particularly General Armstrong, and the challenges faced during the early years of the school. The these experiences illustrate several key themes surrounding education, racial relationships, and the importance of community and morality. 1. Acknowledgment of Support: Washington describes how the financial and moral support from General J.F.B. Marshall and others significantly contributed to the establishment of the school. Their encouragement reinforced the belief that progress was being made, attracting a growing number of students and teachers, primarily graduates from Hampton. The visits from these Hampton alumni not only inspired the Tuskegee community but also drew in local populations eager to witness their impact. 2. General Armstrong’s Influence: Washington shares his initial misconceptions about General Armstrong's views toward Southern white people. Over time, he realizes that Armstrong promotes a philosophy devoid of bitterness, extending compassion towards both races. This influenced Washington to adopt a similar mindset, embracing a spirit of love over hatred and recognizing that aiding the disadvantaged empowers the giver. 3. The Dangers of Prejudice: Washington emphasizes the negative ramifications of prejudice, arguing that actions to undermine the voting rights of African Americans ultimately rot the moral fabric of white Americans. He asserts that dishonesty can become a habit that permeates beyond racial boundaries, urging for a collective effort to alleviate ignorance and foster mutual respect. 4. Industrial Education: Washington notes a shift in educational priorities across the South, spurred in part by Armstrong's advocacy for industrial education. This not only benefited African Americans but also paved the way for educational reforms for white youth, demonstrating a growing acknowledgment of the need for practical skills in both communities. 5. Community Resilience: The narrative details the hardships faced by students, such as inadequate sleeping arrangements and harsh winters. Washington recounts the struggles to provide basic comforts while simultaneously fostering a sense of responsibility among the students. Their willingness to endure discomfort without complaint showcased a shared understanding of the importance of their education. 6. Respect Between Races: Contrary to prevailing beliefs about racial dynamics, Washington shares his personal experiences of respect and kindness he received from both students and local white citizens. He stresses the significance of mutual respect and open communication as essential in forging better relationships and communal harmony. 7. Student Involvement: Washington advocates for a collaborative spirit within the school, demonstrating that students feel a sense of ownership and responsibility towards Tuskegee. Regular meetings and calls for feedback ensured that students contributed to the improvement of their institution, reinforcing their role as active participants in their education. 8. Practical Education and Personal Care: The chapter details the practical aspects of education, such as furniture production and cleanliness standards. Washington underscores the importance of hygiene and self-care, initiating habits that uplifted the students' sense of dignity and fostered societal norms. Instruction in the significance of cleanliness, including the notable emphasis on using toothbrushes, became a cornerstone of the Tuskegee curriculum. In conclusion, Chapter 11 of "Up from Slavery" portrays the foundational years of Tuskegee Institute, filled with challenges and triumphs. Through Washington's experiences, the ideas of industrial education, mutual respect, and the moral responsibilities tied to personal conduct emerge as essential elements for the empowerment of both African Americans and the community at large. The lessons learned extend beyond the walls of the school, aiming to cultivate a more equitable society grounded in shared dignity and collaboration.

Chapter 12 | RAISING MONEY

In this chapter, Booker T. Washington outlines the significant efforts and experiences involved in raising funds for the growing needs of the Tuskegee Institute, illustrating key principles that guide his work and interactions. 1. Expansion Needs: Washington begins by addressing the pressing need for more accommodation for students at Tuskegee, particularly highlighting the decision to construct Alabama Hall to house girls and provide a larger boarding facility. Despite a lack of initial funds, he emphasizes the importance of naming the new building to cultivate community interest and lay the groundwork for fundraising. 2. Community Support: The endeavor attracted contributions from both black and white individuals in Tuskegee, exemplifying the community's willingness to support educational initiatives. Washington notes the significant role of the students themselves, who actively participated by assisting in the construction efforts. 3. Influential Partnerships: During a period of financial uncertainty, Washington received a pivotal telegram from General Armstrong, inviting him to travel north for fundraising purposes. Armstrong's selfless decision to leverage his own resources for the benefit of Tuskegee rather than Hampton underscores a spirit of collaboration and shared purpose within the educational community. 4. Fundraising Philosophy: Washington articulates his philosophical approach to fundraising, articulating two essential rules: to thoroughly promote the institution's work and to remain free from anxiety about the outcomes. He acknowledges that the second rule, especially when faced with financial pressures, has been particularly challenging to practice. 5. Character Traits of Success: Throughout his experience, Washington identifies the need for calmness and self-possession, likening successful fundraisers to the composed demeanor of President McKinley. He expresses admiration for individuals who prioritize the greater good over personal gain, reflecting on how the essence of selflessness and dedication brings fulfillment and joy. 6. Understanding Wealth: Washington encourages a nuanced understanding of wealthy individuals, cautioning against sweeping criticisms of their contributions or perceived lack thereof. He asserts that many are generous in ways that are not publicly recognized. Examples of discreet philanthropists illustrate the often-invisible support that sustains organizations like Tuskegee. 7. The Role of Small Donations: A significant portion of support for Tuskegee has come from small donations rather than large gifts. Washington emphasizes the importance of these contributions and recognizes the consistent support from alumni, illustrating how collective efforts can yield substantial results. 8. Patience and Perseverance: Washington reflects on the patience required in fundraising, sharing a story of a delayed yet generous donation from a man he visited in Connecticut. This experience reinforces his belief in the importance of diligence and the idea that perseverance in outreach often leads to unexpected support. 9. Strategic Communication: The chapter highlights Washington's deliberate approach in crafting appeals for support, showcasing how he utilizes clear, fact-based requests to engage potential donors. The case of securing a library building from Andrew Carnegie exemplifies this strategy, demonstrating how focused, well-structured requests can attract significant financial backing. 10. Businesslike Approach: Washington stresses the importance of maintaining high standards of business ethics in all financial dealings, ensuring that Tuskegee operates transparently and efficiently, thereby gaining the confidence of donors. Through these experiences and insights, Washington illustrates the intricate dance of fostering relationships, communicating effectively, and fostering a culture of philanthropy that collectively drives the mission of Tuskegee Institute forward. The narrative serves as a testament to his unwavering dedication to uplifting the African American community through education and self-improvement.

Chapter 13 | TWO THOUSAND MILES FOR A FIVE-MINUTE SPEECH

In the early days of the Tuskegee Institute, Booker T. Washington encountered a significant challenge: numerous deserving students were unable to afford the tuition fees, prompting the establishment of a night school in 1884. This initiative aimed to help impoverished men and women secure an education while they worked during the day in various trades. Initially starting with just a dozen students, the night school flourished, demonstrating a transformative commitment to education. By requiring students to balance work and study, Washington emphasized that those willing to endure the rigors of labor in exchange for knowledge possessed the perseverance necessary for further education. Transitioning from night school to day classes, students continued a dual focus on academic learning and industrial training, all while engaging in manual labor, which was deemed equally vital to academic success. This holistic approach proved effective, as many graduates, having endured the night school’s rigorous demands, went on to thrive in both their trades and academia. Notably, the industrial side of education became just as respected as its academic counterpart. Though a strong emphasis was placed on vocational training, Washington did not overlook the importance of spiritual growth. Tuskegee operated as a non-denominational institution grounded in Christian values. Various religious activities reinforced the moral development of students, ensuring that their education encompassed both practical skills and ethical principles. Washington’s personal life intermingled with his professional endeavors when he married Miss Olivia Davidson in 1885. Together, they navigated the challenges of running the school and securing necessary funding, working tirelessly for eight years until her untimely death in 1889. His foray into public speaking began unexpectedly when he attended a series of meetings in the North, where he was invited to address the National Educational Association. This pivotal moment not only introduced him to a broader audience but also set the stage for his growing visibility as a leader speaking on race relations. Washington approached these speaking engagements with a strategic intent, emphasizing positive relations and fostering understanding rather than critique, which often garnered him unexpected support from white audiences. He advocated for a focus on mutual respect and the value of the African American community in societal contributions. Washington's evolving reputation eventually led him to address a crucial moment in his career at the 1895 Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition. His initial speech at a smaller engagement built the momentum that would propel him into the national spotlight. He was able to articulate a vision of progress through education and mutual respect between races, expressing a fundamental belief that the path to acceptance lay in the economic empowerment of African Americans. This speech, however, came after a deliberative process where he weighed the potential backlash from both white and black communities. He aimed to balance truthfulness to his race while also being palatable to the white South, recognizing the historical weight of his presence on such a stage. Washington vividly recalls the anxieties that layered his journey to the Exposition, feelings compounded by his humble beginnings and the pressures of representing his race to a mixed crowd of influential figures. On the day of the address, despite initial nerves, Washington captured the attention of a diverse audience with his measured yet firm approach. His message resonated deeply, praising the contributions of both races while advocating for practical advancements in education and economic success. This moment galvanized support for African American development and set a precedent for future racial dialogues. Through his experiences, Washington consistently returned to a central theme: the belief that industriousness and education would ultimately elevate the African American community, proving their integral value within society. He fostered both personal and communal advancement, maintaining that the strongest approach to civil rights lay in economic progress and the building of sincere relationships across racial lines.

Chapter 14 | THE ATLANTA EXPOSITION ADDRESS

In Chapter 14 of "Up from Slavery," Booker T. Washington recounts his significant address delivered at the Atlanta Exposition, an event that symbolized both recognition of African American contributions and the potential for racial cooperation. His speech aimed to bridge the gap between white and black communities in the South, emphasizing common interests and shared goals. Washington's remarks can be distilled into several key principles that articulate his vision for the future of race relations and social progress. 1. Importance of Cooperation: Washington stresses that one-third of the Southern population is of African descent, and any effort towards the region’s advancement cannot overlook this demographic. He emphasizes that mutual understanding and cooperation will be crucial for the prosperity and progress of both races. 2. Call to Action: He uses the metaphor of a ship in distress, suggesting that African Americans should "cast down your bucket where you are." Instead of seeking opportunity elsewhere, they should engage with their immediate communities, focusing on agriculture, mechanics, commerce, and civil service to improve their circumstances. 3. Dignity of Labor: Washington believes that all forms of labor hold dignity, urging his audience to appreciate the value of hard work in various trades rather than aspiring solely to political positions. He argues that true prosperity stems from a commitment to skill and productivity, rather than superficial ambitions. 4. Strategic Relations with the White Population: Washington encourages African Americans to nurture friendships with their white neighbors as a way to foster peace and prosperity. He highlights the loyalty of black Americans to their white counterparts throughout history, affirming that they will continue to be steadfast allies in future endeavors. 5. Long-Term Vision for Rights: He expresses faith that political rights for African Americans will eventually come through natural evolution rather than external pressure. Washington asserts that progressive change should stem from the recognition of merit rather than force, insisting that gains will arise from a strong character and accumulated wealth. 6. Emphasis on Education and Self-Improvement: Washington underscores the significance of education in realizing the potential of the African American community. He believes that both races will prosper when the African American population is empowered and educated, which will, in turn, strengthen societal ties. 7. Response to Criticism: Despite initial enthusiasm for his speech, Washington faced backlash from some within the African American community who felt he was too conciliatory towards whites. Nevertheless, he remained steadfast, asserting that honest dialogue and self-reflection would ultimately lead to improved conditions for his race. 8. Enduring Friendships: Washington shares anecdotes about his continued relationships with influential figures, including President Grover Cleveland, exemplifying a real, personal commitment to strengthening racial ties and advocating for the interests of his community. In summary, Washington's address at the Atlanta Exposition represented a pivotal moment not only for his personal journey but also for the broader struggle for African American advancement. His message resonated across racial lines, advocating for cooperation, dignity in labor, and a commitment to education—principles that he believed would foster genuine progress and unity in society. The enduring impact of his speech and the subsequent recognition he received illustrated the potential for building a collaborative future, rooted in mutual respect and shared goals.

Key Point: Importance of Cooperation

Critical Interpretation: Imagine standing at the crossroads of opportunity, where your decisions can directly impact not just your own life but also the lives of those around you. Just as Booker T. Washington emphasized in his address at the Atlanta Exposition, the essence of progress lies in cooperation and mutual understanding. As you navigate your own path, consider how powerful communal efforts can be; reaching out to collaborate with others can create a ripple effect of growth and achievement in your community. Whether it’s in your workplace, neighborhood, or even amongst friends, embracing the idea that together you can achieve more than alone inspires not only personal ambition but also cultivates a spirit of unity that uplifts everyone involved. As you strive to make your mark, remember Washington’s wisdom: true prosperity flourishes when you cast your bucket down into the community you call home.

Chapter 15 | THE SECRET OF SUCCESS IN PUBLIC SPEAKING

In Chapter 15 of "Up from Slavery," Booker T. Washington reflects on the transformative power of public speaking, particularly through his own experiences as an orator. His account begins with a noteworthy event at the Atlanta Exposition, where he delivered a speech before a predominantly white audience. The presence of notable figures like President Cleveland heightened the occasion's significance, representing a shift in race relations in the South. 1. The Impact of Historic Speaking Engagements: Washington's Atlanta address was a landmark event that marked a new epoch in Southern history. Mr. James Creelman characterized Washington's speech as electrifying and a moral revolution in America, highlighting that a Black man addressed a white audience in such a significant context for the first time. The public reaction was overwhelmingly positive, with signs of deep emotional connection among audience members, including spontaneous applause and tears. 2. Nervousness and Connection: Despite his success, Washington confessed to feeling intense nervousness before speaking engagements, often questioning why people chose to hear him. However, once he began to speak, he quickly found a sense of relief and connection with his audience, which transformed his anxiety into a thrilling experience. His ability to sense and engage with the audience's feelings is a critical component of his speaking style. 3. Authenticity and Depth in Communication: Washington emphasized that public speaking should stem from genuine conviction, rather than mere performance. He advocated for delivering meaningful messages that resonate with the audience, touching on the importance of facts over generalizations. He believed that successful communication hinges on creating an enjoyable experience where the audience remains engaged. 4. Preferred Audiences: Throughout his career, Washington noted a preference for speaking to business professionals and Southern audiences, who generally displayed enthusiasm and responsiveness. Interactions with these groups, including various organizations and academic institutions, provided him opportunities to share the message of education and self-help for African Americans. 5. Community Engagement and Results: Washington discussed his efforts beyond the main campus of Tuskegee, highlighting a series of meetings across different communities. These sessions not only fostered goodwill between races but also enabled Washington and his wife to gather firsthand knowledge about the conditions of African Americans, enhancing their understanding of the challenges faced by their communities. 6. Addressing Critiques: Washington's public speaking sometimes drew criticism, particularly from the Southern press, but he stood firm in his beliefs and clarified his intentions during engagements. He made it clear that he only addressed audiences according to principles of mutual respect and shared humanity, emphasizing the importance of dialogue in overcoming prejudices. 7. Organizational Principles: Washington shared insights into how he managed his commitments without compromising the operation of Tuskegee Institute. His emphasis on delegation and collaboration allowed for an effective educational environment that ran smoothly even in his absence. 8. Personal Reflections and Recreation: Washington revealed his approach to finding balance in his hectic schedule. He prioritized daily organization and a commitment to physical fitness and healthy living. Activities like storytelling with his family, gardening, and enjoying nature brought him profound joy and served as essential outlets for relaxation amidst his laborious work. In summary, Chapter 15 conveys Washington’s profound connection to public speaking as an instrument of change and understanding, illustrating how his approach combines personal authenticity, community engagement, and unwavering commitment to African American progress. Through his oratory and organizational skills, he embodies the spirit of resilience and empowerment that he sought to instill in his race.

Chapter 16 | EUROPE

In Chapter 16 of "Up from Slavery," Booker T. Washington provides a personal glimpse into his family life and reflects on significant experiences during his trip to Europe. The chapter begins with both the emotional and practical support that Mrs. Washington, a dedicated educator and community leader, offers not only him but also the Tuskegee community through various initiatives such as mothers' meetings and a women’s club. Their children, Portia, Booker Taliaferro, and Earnest Davidson, are described with admiration as they pursue their own academic and vocational goals, showcasing the strong familial bonds and values instilled in them. One of the poignant themes in this chapter is Washington's profound sense of duty and commitment to his work, often at the expense of time with his family. He openly expresses a longing for the simple joys of domestic life and the satisfaction derived from connecting with students at Tuskegee during evening prayers. Nevertheless, when an unexpected invitation to Europe arises, through the generosity of friends and supporters, Washington grapples with feelings of hesitance about departing from his responsibilities. His reflections on this surprise trip, planned for May 10, lead him to confront his previous notions about travel and leisure, which felt foreign given his background of hardship and labor. Despite his reluctance, the encouragement from his community convinces him to embark on this journey, symbolizing a significant personal transformation from a life of constant toil to one of brief respite. As Washington embarks on the voyage aboard the ship Friesland, he experiences a sense of overwhelming relief and wonder, having never traveled in such a manner before. The warmth and kindness he is shown by fellow passengers, especially from Southern men and women, contradict his earlier fears of potential discrimination. Once in Europe, Washington’s experiences in major cities like Antwerp, Paris, and London deeply inspire him. He is welcomed warmly in a variety of social settings, where he engages with prominent individuals, including the American Ambassador and other influential figures. His encounters challenge his preconceived notions about class and race, affirming his belief in the power of hard work and merit over one's background. Throughout his travels, Washington emphasizes the need for the African American community to provide value that transcends racial barriers. He notes the importance of skill and excellence in any vocation, believing that recognition and respect will follow those who achieve high standards, regardless of race. Illustrating this through the success of the artist Henry O. Tanner, he consistently returns to the theme that dedication and quality in one’s work forge pathways to respect and opportunity. As the chapter concludes, Washington reflects on the significance of invitations he received upon returning home from various communities, showcasing the respect and esteem he has earned. These experiences reflect a notable shift from his humble beginnings to becoming a respected figure, further anchoring his belief that personal responsibility and commitment to excellence can lead to communal uplift. In summary, the essential themes in this chapter are as follows: 1. Value of Family and Community: Washington illustrates the support from his wife and their children's individual pursuits, highlighting the importance of education and community engagement. 2. Conflict Between Responsibility and Personal Desire: His internal struggle regarding the trip symbolizes the balance many individuals face between work obligations and the need for personal rejuvenation. 3. Transformation Through Experience: The journey to Europe represents not only physical travel but also Washington’s personal growth, confronting his past and societal expectations. 4. Merit Over Race: Washington reinforces the idea that success is achievable through excellence in one's efforts, providing a powerful counter-narrative to racial bias. 5. Recognition and Respect: The invitations and receptions following his travels serve as a personal affirmation of his work and underscore the potential for positive societal change through individual contributions. Ultimately, Washington’s chapter conveys that achievement, grounded in hard work and ethical contributions, can transcend racial divides, leading to broader understanding and acceptance within society.

Chapter 17 | LAST WORDS

In this reflective and profound chapter of "Up from Slavery," Booker T. Washington shares pivotal moments of his life, characterized by remarkable surprises and a sense of fulfillment that comes from selfless service. His narrative emphasizes the joy found in helping others and the importance of striving for a life marked by unselfishness and utility. 1. Washington recounts the poignant visit of General Samuel C. Armstrong to Tuskegee, nearly a year after he suffered a stroke. Despite his severe limitations, General Armstrong's visit lights a fire in Washington to continue his work in uplifting the African American community, reasserting the dual obligation to improve the conditions of both Black citizens and poor white individuals in the South. Armstrong's enduring spirit during this visit serves as a powerful reminder to Washington of the impact one can have, even amidst personal trials. 2. The chapter highlights a significant personal milestone for Washington when he received an honorary Master of Arts degree from Harvard University. This unexpected recognition stirred deep emotions within him as he reflected on his arduous journey from slavery to becoming an influential educator. The invitation from Harvard was more than an honor; it symbolized an acknowledgment of his unwavering commitment to the education and upliftment of his race. 3. Washington's journey to Harvard laid the groundwork for an examination of racial dynamics in America, stressing the necessity for the privileged to engage with the underprivileged. He articulated a vital message about fostering better relations between different races, asserting that true progress comes from elevating the marginalized while also fostering understanding for their plight. 4. The narrative transitions to Washington's bold and ambitious plans for Tuskegee Institute, highlighting his vision for the institution to be recognized at the highest levels of government. His efforts to secure a visit from President McKinley culminate in a monumental event where not only the President but also other dignitaries visit the school. This visit symbolizes a significant acknowledgment of the progress being made at Tuskegee and represents a communal pride among both Black and white citizens of Alabama. 5. Washington reflects on the tangible growth of Tuskegee Institute, from its humble beginnings to becoming a significant educational institution with a robust curriculum and an expanding student body. He notes the successful implementation of a practical educational framework that not only prepares students academically but also instills a strong work ethic, reinforcing the idea that labor is both dignified and essential. 6. The enduring importance of community engagement is underscored through the establishment of conferences aimed at addressing the conditions and needs of African Americans. These gatherings foster collaboration and strategizing for socioeconomic upliftment, highlighting Washington's belief in collective progress. 7. Throughout the chapter, Washington’s commitment to continuous improvement in education and community well-being resonates strongly. His work transcends mere academic achievement; he emphasizes moral character and self-sufficiency as vital components for true progress within the African American community. 8. Washington concludes on a hopeful note as he reflects on his life journey, using the city of Richmond as a backdrop for his return as a respected leader. This moment of reconciliation and recognition bridges the past with the present, allowing both races to come together to celebrate shared goals of progress and unity. In summation, Washington's narrative serves as a testament to the power of resilience, the imperatives of education and service, and the possibilities that arise when communities come together in mutual respect and support. Through his life's work, Washington not only uplifts his own race but also fosters an understanding imperative for societal harmony, leaving a legacy that emphasizes the interconnectedness of all individuals, regardless of race.