Last updated on 2025/05/03

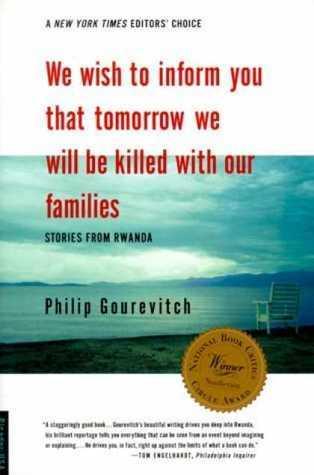

We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, Stories From Rwanda Summary

Philipgourevitch

A Chronicle of the Rwandan Genocide's Impact.

Last updated on 2025/05/03

We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, Stories From Rwanda Summary

Philipgourevitch

A Chronicle of the Rwandan Genocide's Impact.

Description

How many pages in We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, Stories From Rwanda?

384 pages

What is the release date for We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, Stories From Rwanda?

In "We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families," Philip Gourevitch masterfully chronicles the harrowing aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, weaving together haunting narratives that illuminate the profound human impact of violence and loss. Through a blend of meticulous journalism and poignant storytelling, Gourevitch exposes the complexities of identity, memory, and survival amidst the atrocity that claimed nearly a million lives in just one hundred days. As he delves into the lives of both victims and perpetrators, the book challenges readers to confront the uncomfortable truths of collective responsibility and the haunting legacies that endure long after the brutality fades. Engaging and expertly crafted, this work invites readers to reflect on the fragility of peace and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of unspeakable horror.

Author Philipgourevitch

Philip Gourevitch is an acclaimed American journalist and author best known for his incisive coverage of the Rwandan genocide, which he explores in depth in his powerful book "We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families." Born in 1961, Gourevitch has made significant contributions to both literary and political journalism, with his keen eye for detail and ability to convey the complexities of human suffering and resilience. His work often delves into themes of conflict, memory, and the aftermath of violence, reflecting not only his personal engagement with the subjects he tackles but also a broader commitment to understanding socio-political realities. With a background that includes writing for prestigious publications such as The New Yorker, Gourevitch's writings are characterized by their profound empathy and a quest for truth in the grim aftermath of humanitarian crises.

We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, Stories From Rwanda Summary |Free PDF Download

We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, Stories From Rwanda

chapter 1 |

In the province of Kibungo, Rwanda, the Nyarubuye church witnessed horrific atrocities during the genocide in April 1994, where many Tutsis lost their lives. The author recounts his visit to the site a year later, accompanied by Canadian military officers, where he encountered the remains of approximately fifty decomposed bodies scattered throughout a classroom. The stark reality of the scene was numbing; despite their decomposition, the dead bodies evoked a strange blend of beauty and horror. The visceral imagery of skeletal remains amidst personal belongings underscored the tragic humanity of those who had once lived. The haunting silence of Nyarubuye was marked not just by the presence of the deceased but by the memories of violence and betrayal that haunted the lives of survivors. The author reflects on the unity of the dead and their killers—neighbors and friends turned adversaries—who were incited by an ideology labeled "Hutu Power." This ideology provided justification for the mass killings; it stirred fear, hatred, and eventually led to a systematic extermination of the Tutsi population. The meticulous process of planning, executing, and rationalizing the killings indicated that the violence was neither impulsive nor chaotic, but rather a dark manifestation of organized hatred. The killers worked in an assembly line fashion, day after day, adhering to a gruesome schedule that saw countless Tutsis murdered. Nightly feasts revealed a disturbing juxtaposition between daily life and acts of violence; having participated in such atrocities, the killers would relax and celebrate their actions. As the author continued his exploration of Nyarubuye, he sensed the weight of despair and the unfathomable nature of the violence. An encounter with Sergeant Francis, a Tutsi soldier, revealed further layers of trauma as he recounted the systematic brutality directed particularly at women, emphasizing an element of sexual violence intertwined with the broader campaign of extermination. The narrative then shifts to the broader implications of the genocide on Rwanda's landscape and demographics. Joseph, a local man, expresses the sorrow felt in the face of the stunning beauty of Rwanda—his family's trauma overshadowing the country's rich natural allure. The physical and psychological scars left by the genocide were evident, yet as the author traveled through the land, remnants of the past were often invisible. While survivors grappled with the haunting memories, many questioned how such widespread violence could occur: they pondered not only how some were able to commit such acts but also why many did not resist or fight back. Survivors' reflections highlight the deep-rooted culture of fear that pervaded Rwandan society. Acceptance of death became a psychological coping mechanism among Tutsis, while Hutus were driven by societal pressures and authority to join in the violence. As one survivor noted, individuals who might have been reluctant to kill were coerced into compliance, revealing a chilling transformation where survival instinct became intertwined with complicity. Through testimonies from various survivors and observers, the author unveils the complexities of human behavior under duress—conformity, fear, and the quest for survival became intertwined in the fabric of the genocide. These reflections serve not just as an exploration of history but as a moral examination of humanity's capacity for both violence and empathy. Ultimately, the chapter compels the reader to confront the difficult truths of Rwanda's past, offering a stark reminder of the fragility of human morality in the face of organized hatred. The challenge for the world is not merely to remember the horrors of genocide but to understand its roots, ensuring history's lessons guide future actions against such atrocities.

Key Point: The fragility of human morality in the face of organized hatred

Critical Interpretation: As you navigate the complexities of your daily life, consider how easy it is to turn a blind eye to the injustices around you. Reflect on the chilling reality that in times of moral crisis, individuals often succumb to conformity or fear rather than standing up against wrongdoing. This chapter compels you to recognize your own agency; the choices you make in moments of discomfort define your moral fabric. Use this understanding as a call to foster empathy and courage in your interactions, ensuring that you not only remember the past but actively engage in preventing such atrocities from repeating in any form. In a world still rife with division and hate, embrace your power to challenge ideologies that dehumanize others, transforming moments of silence into actions that affirm our shared humanity.

chapter 2 |

In a poignant narrative, the second chapter of Philip Gourevitch's "We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families" presents a harrowing account of the Rwandan genocide through the eyes of Samuel Ndagijimana, a medical orderly, and Manase Bimenyimana, a colleague who experienced the chaos and violence in the Mugonero Adventist complex. 1. As the journey begins in the hills of Rwanda, the village of Mugonero starkly contrasts with the massacre memorial at Nyarubuye. This village, home to a significant Seventh-Day Adventist mission, housed a hospital that initially served as a refuge for those fleeing the violence of the genocide. Samuel recalls a time, before the violence escalated, when life was simple and dominated by the shared faith of the community, suggesting an innocence gradually shattered by growing Hutu militancy. 2. The situation rapidly deteriorated after the assassination of President Habyarimana on April 6, 1994. Samuel describes a palpable shift in the atmosphere—conversations ceased, and fear gripped the community, particularly among Tutsis who watched as the local leaders organized violence. The dynamics at the hospital shifted as violence moved closer, with Tutsi families seeking sanctuary within its walls in apparent hope and trust in their Christian community. 3. The narrative unfolds with accounts from refugees who escaped neighboring areas only to witness gruesome violence against their kin. As the hospital filled with Tutsi refugees seeking safety, the leaders of their own church, including Dr. Gerard and Pastor Elizaphan Ntakirutimana, revealed a betrayal as they allied themselves with the Hutu attackers, sealing the fate of many. 4. On April 16, the Tutsi refugees’ nightmare culminated in a brutal assault on the Adventist complex, with Samuel noting the lack of weapons or food, the desperation palpable as they faced armies armed and organized by their supposed protectors. Even the police, who had promised safety, joined in the violence, reflecting the systematic betrayal by figures of authority. 5. With thousands of Tutsis killed within days, Kibuye became a graveyard. The realities of displacement and survival emerged as Manase and Samuel fled into the mountains, where they encountered both the despair of death and the faint glimmer of community among other survivors. The narrative starkly details the brutality of the genocide, where Tutsis were systematically hunted and eliminated in a calculated campaign that exploited both fear and betrayal. 6. Samuel's journey included a terrifying escape across Lake Kivu to Zaire, while Manase fought for survival in the mountainous terrain of Bisesero, where hope for resistance began to dwindle under persistent assault. The mountains, while offering some refuge, also bore witness to the ruthlessness of the Hutu militia, who employed brutal tactics against the Tutsi population, further symbolizing the genocide’s depth of depravity. 7. Amidst this catastrophic backdrop, the bond between survivors remained vital, with Samuel and Manase navigating the complexities of trust and betrayal within their compatriots and their own faith communities. Their stories exemplify the range of human experience during this dark chapter, from the hope of salvation to the despair of survival, interwoven with the relentless march of violence that sought to eradicate an entire ethnic group. In conclusion, this chapter encapsulates the horrors of the Rwandan genocide, illustrating the fragility of faith, community, and survival in the face of overwhelming brutality and betrayal, as the lives of Samuel and Manase reflect both the individual and collective tragedies endured during this period.

Key Point: The fragility of faith and community amidst chaos

Critical Interpretation: Reflecting on Samuel and Manase's harrowing experiences during the genocide, consider how easily trust can be shattered, even within those we hold dear. Their story is a reminder that faith can be both a sanctuary and a source of profound betrayal. In your own life, this chapter challenges you to cultivate true connections and to value genuine compassion over mere solidarity, urging you to engage authentically with others. As you navigate your own challenges, remember that community can either uplift or destroy; strive to be the thread that weaves hope and resilience in times of darkness.

chapter 3 |

Rwanda, known for having some of the best roads in central Africa, presents a paradox with its infrastructure. Although Kigali boasts a network of two-lane tarmac roads connecting most provincial capitals, the route to Kibuye remains a treacherous, unpaved journey, offering a metaphor for the nation’s historical scars. The dilapidated state of the Kibuye road is no coincidence; it symbolizes the long-standing neglect and prejudice experienced by Tutsis, once derogatorily referred to as inyenzi, or "cockroaches." This neglect was compounded during the 1980s when funds earmarked for road improvements in Kibuye disappeared, leaving the area isolated. The arduous seventy-mile trek from Kigali to Kibuye could typically be covered in three to four hours, yet a convoy's attempt took nearly twice that due to rough weather and dangerous road conditions. During this journey, the author encountered soldiers armed with Kalashnikovs who warned them against drawing attention. They were in the midst of a war-torn landscape that still found echoes of the 1994 genocide two years later, as Hutu militia continued to terrorize the region. The landscape came alive with sounds of rain, dense fog, and the chilling distress signals of a woman in the valley, illustrating the communal responsibility and moral obligation inherent in Rwandan society. The call for help from the valley revealed a culture where individuals felt compelled to respond and support their neighbors—an obligation that oversaw their social interactions. This reflection on community highlights the dual nature of Rwanda's societal norms. On one hand, there is a communal bond that drives individuals to protect one another. Yet, the author ponders a darker reality: what happens when this sense of duty is manipulated, leading to atrocities? The question remains whether moral obligations can persist in a society that has seen the perversion of innocence turn into complicity with evil. As we transition to recounting the aftermath of the genocide, Pastor Elizaphan Ntakirutimana emerges as a contentious figure. After fleeing Rwanda, he settled in Laredo, Texas, only to face accusations for his role in the Mugonero massacre, where Tutsis sought refuge. Complaints from Tutsis in the U.S. led to governmental inquiries, indicating the complexity of justice in the aftermath of such tragedy. The dichotomy between the pastor's presented benevolence and the grave accusations against him raises troubling questions about accountability. When the pastor and his son eventually faced legal scrutiny, an indictment based on testimonies emerged, recounting incidents where the pastor allegedly instructed Tutsis to take refuge at his congregation, only to later participate in inflicting violence upon them. Through interviews with family and associates, the author dissects the intricate layers of denial, self-preservation, and the implications of having a mixed heritage in a society fractured by ethnic conflict. The pastor’s response to the accusations reflects a denial bordering on incredulity; he vehemently claimed innocence, asserting he never endorsed violence. His views on the rampant chaos of the period exemplified a refusal to accept the reality of genocide, attributing blame to others while invoking a sense of victimhood. The clash between the views of the pastor's family—particularly the supportive defense of his son—and the voiced grievances of the survivors creates a tableau of guilt and innocence, complicity, and the challenge of reconciliation. Ultimately, the fate of Elizaphan Ntakirutimana encapsulates the struggle for justice in a post-genocide society. His arrest passes under the radar, sparking little media attention, contrasting sharply with the enormity of the allegations against him. The fact that a man accused of orchestrating large-scale violence against his own congregation retained the privilege of a green card in the United States highlights the challenges of seeking justice within the borders of systemic neglect and bureaucratic intricacies. Through the lens of multifaceted relationships among survivors, perpetrators, and the socio-political structure in exile, the narrative emphasizes a profound collective trauma. It calls for a reflective understanding of personal accountability, communal governance, and the enduring quest for reconciliation in Rwanda, ultimately cautioning about the cyclical nature of history and the need for vigilance against repeating the past. Recognizing the fragility of humanity in the face of collective memory and historical injustices is essential for the healing and future of a nation still grappling with its identity.

Key Point: The importance of communal responsibility in times of crisis

Critical Interpretation: Imagine a community where, in the face of darkness and adversity, each person feels a palpable sense of duty to aid their neighbor—this is the essence of Rwanda’s moral fabric, as illuminated in the stories of people compelled to respond to distress signals. Let this serve as a profound reminder in your life: in moments of hardship, whether in personal struggles or societal crises, your moral obligation to support others can foster resilience and healing. You are encouraged to embrace a spirit of empathy and active participation; acknowledge that your actions—no matter how small—can significantly impact those around you, binding your community together in solidarity against the odds of isolation and neglect. This call to moral action is a powerful catalyst for change, urging you to step forward and contribute positively, ensuring no one feels abandoned in their time of need.

chapter 4 |

In the narrative presented in this chapter, the complex history of Rwanda unfolds through a tale of identity, power struggles, and colonial legacy. The origins of the Hutu and Tutsi peoples, often perceived as distinct ethnic groups, are traced back to a rich tapestry of intermingling cultures that defy simple categorization. Initially, Rwanda was home to the Twa, a marginalized group whose lineage can be traced to cave-dwelling pygmies, while Hutus and Tutsis eventually migrated to the region, blending into a society where the distinctions between them became less pronounced through shared language, religion, and intermarriage. Over time, however, these identities became enshrined in a social hierarchy that favored Tutsis over Hutus, primarily due to the latter’s role as agriculturalists versus the Tutsis’ status as herders. This distinction led to a perception of Tutsis as a political and economic elite, especially during the reign of Mwami Kigeri Rwabugiri in the late 19th century, who solidified power through military expansion and strategic alliances. Yet, the historical understanding of these identities is muddied by the oral traditions that prevail in Rwanda, shaping views based on the perspectives of those in power. Following the rise of colonial powers, Rwandan society experienced significant disruptions. The arrival of European explorers like John Hanning Speke set the stage for colonial domination as they imposed external narratives that classified the Rwandan people in terms of racial superiority and inferiority, cementing the divide between Hutus and Tutsis through the Hamitic hypothesis. This theory, propagated by colonial administrators, unjustly portrayed Tutsis as a superior race, leading to the stigmatization of Hutus. The German colonizers first, followed by the Belgians after World War I, further exacerbated these divisions through policies that reinforced the existing social structures, empowering Tutsi elites while disenfranchising the Hutu majority. Ethnic identity cards issued during the colonial period became symbols of permanent separation, fostering a culture wherein Hutu and Tutsi discourses increasingly defined themselves in opposition to one another. As pressure mounted within Rwanda for political change, the late 1950s saw the eruption of violence, marked by the infamous beating of a Hutu activist, which served as a catalyst for widespread uprisings against the Tutsi elite. This "wind of destruction" signaled the beginning of a revolution, transforming political dynamics while entrenching ethnic identities deeper than ever. The resulting upheaval saw Tutsi families displaced from their homes, giving rise to a new Hutu-dominated regime that often mirrored the atrocities of the past under colonial rule. Despite the initial hopes for a more equitable political landscape, power transitioned into the hands of Hutu leaders who perpetuated the narrative of tribalism and division, ultimately leading to oppressive governance that reflected the same injustices Tutsis had previously inflicted upon Hutus. Rwanda's post-colonial reality was steeped in a cycle of violence, where the revolutionary ideals of justice and equality were suffocated by the relentless desire for control and dominance. As tensions simmered and resentment festered, Rwanda's historical narrative echoed the biblical tale of Cain and Abel, reflecting on the tragedy of fraternal violence rooted in identity, jealousy, and political ambition. The tragic legacy of colonialism and ethno-political manipulation culminated in a society deeply fractured by the very divisions that foreign powers had sown, setting the stage for future conflicts that would resonate through Rwanda's history. Through the interplay of power, identity, and the haunting specter of the past, Rwanda's tumultuous journey serves as a poignant reminder of the consequences of manipulated narratives and the enduring quest for justice amidst tragedy.

Key Point: The Danger of Manipulated Narratives

Critical Interpretation: In reflecting on the tragic events of Rwanda, you might feel a deep sense of urgency to interrogate the stories that shape your own identity and community. The chapter reminds you that history, as we know it, often comprises narratives crafted by those in power, and it is essential to recognize the possibility of distortion in these accounts. By actively seeking out diverse perspectives and understanding the complexities of your own cultural background, you can rise above simple categorizations and tribalism. This awareness empowers you to foster inclusion and empathy in your own circles, ultimately contributing to a more just and harmonious society by refusing to allow superficial divisions to dictate interactions and relationships.

chapter 5 |

Odette Nyiramilimo's compelling narrative begins with her recollections of growing up during an era marked by systemic violence against Tutsis in Rwanda. Born in 1956 in Kinunu, Gisenyi, Odette's early memories of the genocide comprise fleeing into the bush with her family, witnessing houses ablaze, and feeling the profound loss of normalcy as they lived without security or stability. Her family, deeply impacted by the tragedies of 1963 when her father anticipated death upon seeing his brothers taken away, exemplifies the fear and displacement faced by Tutsi families under a regime that incited violence against them. As she recounts her journey, Odette highlights the years marked by oppression and social stratification under President Kayibanda, who, by fostering ethnic hostilities, perpetuated a narrative that reduced Tustis to mere statistics, claiming they constituted only nine percent of the population. This marginalization led to a cultural identity crisis for many Tutsis—losing their homes and safety contributed to their collective trauma. A pivotal moment in Odette’s life was her father's experience of being compelled to assume a Hutu identity for survival, which underscores the extreme measures families took to navigate the treacherous socio-political landscape. The violence escalated in 1963 with the Tutsi guerrilla invasion, leading to organized massacres and the displacement of countless families. Experts, like French schoolteacher Vuillemin, documented the atrocities, emphasizing the indifference of international observers, which only complicated the humanitarian crisis. Through Odette’s perspective, the impact of the systematic destruction of Tutsi communities is personal and heart-wrenching. When her family opted to remain in Rwanda against the odds of survival, it reflects the deep-rooted ties to their land and heritage. Even as shifts in power occurred with Habyarimana’s coup in 1973 promising peace, the specter of exclusion remained, as regulations continued to suppress Tutsi societal reintegration. Odette's life path took her to teachers' college, where she faced renewed threats of violence disguised as bullying, illustrating the continuous climate of fear and distrust in educational settings. Her expulsion revealed the blatant discrimination against Tutsis, particularly amidst rising tensions fueled by events in Burundi, ultimately shaping the collective narrative around Tutsi identity as a target for persecution. Despite her struggles, Odette's resilience became evident as she pursued a career in medicine, aided by allies who shielded her from the harsh realities of government scrutiny. Her dedication to her studies and her eventual rise as a respected doctor became a beacon of hope amid the backdrop of societal turmoil. However, even in professional spaces, Odette was constantly reminded of her ethnicity, with brutal encounters exposing the fragile lines within Rwanda's increasingly polarized society. Upon reflecting on her life before and after Habyarimana’s regime, Odette shows us the delicate interplay between personal agency and the overarching political machinations that dictated lives. The irony of her graduating as a doctor only to encounter prejudice within her own community highlights the persistent struggle of survivors grappling with their identities amid a landscape littered with memories of violence and fear. Finally, the vivid recollection of a moment of sexual harassment during her studies introduces a different type of victimization, subtly suggesting that the personal experiences of women in Rwanda were intricately linked to the broader issues of power and oppression across gender and ethnicity. Odette’s story weaves through moments of hope, determination, and the undeniable weight of history, ultimately depicting a survivor who faces the specter of her past while striving to carve a future—a testament to the resilience of the human spirit amid unimaginable adversities. Each memory she shares serves as a reminder of the complexities of survival within a narrative defined by the politics of ethnicity, and her journey illustrates how the legacies of violence and resilience shape identities in profound ways.

Key Point: Resilience Amid Adversity

Critical Interpretation: Odette's narrative embodies the transformative power of resilience, urging you to confront your own challenges with unwavering strength. No matter how daunting your circumstances might seem, the story of Odette illustrates that personal agency can thrive even in the most oppressive environments. Let her journey inspire you to rise above the fears that tether you, recognize your inherent worth, and pursue your passions with relentless determination despite the barriers you may face. Remember, each setback can be a stepping stone towards your true potential, just as Odette transformed her trauma into a profound commitment to healing others.

chapter 6 |

In the evolving political landscape of Rwanda during the era of the Second Republic, disappointment and alienation among various groups, including Hutus and Tutsis, were on the rise. The totalitarian regime of President Juvénal Habyarimana, who boasted a ludicrous ninety-nine percent voter approval, became increasingly oppressive. Central to his rule was a patronage system that favored his northwest constituents, leaving southern Hutus feeling marginalized. Despite an appearance of stability and gradual improvement in living conditions, the stark reality of pervasive poverty persisted for most Rwandans, while the elites flourished under Habyarimana’s regime. Internationally, Rwanda was viewed favorably amid a turbulent postcolonial Africa, garnering substantial financial support from countries like Belgium, France, and the United States. As economic challenges arose in the late 1980s, particularly following a significant drop in coffee and tea prices, the established power structures in Rwanda began to unravel. The intertwining relationships between the political elite, the military, and state resources became increasingly evident, casting the President more as a pawn within a web of local power brokers than a dominant force. Amidst this backdrop of corruption and growing discontent, Habyarimana's wife, Agathe, wielded considerable influence and was often seen as the real power behind the throne. The political turbulence further escalated when a rebel group, the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF), launched an invasion from Uganda in 1990, claiming to fight against tyranny and corruption. The arrival of the RPF reinvigorated the Habyarimana regime, which manipulated national sentiments by framing the invasion as an existential threat. This strategy enabled the government to justify increasingly repressive measures against perceived “enemies,” leading to widespread preemptive arrests of Tutsis and dissenting Hutus, creating an atmosphere of fear and mistrust. The regime's approach was underscored by a lack of genuine political reform, despite international pressures for democratization, which only fueled further anxieties within the ruling class. As the RPF began to gain traction, local officials even incited communal violence, leading to brutal massacres like that of Kibilira, marking a sinister precursor to the coming genocide. This initial outbreak of violence demonstrated the regime’s intent to maintain control through fear, animosity, and scapegoating, effectively denying a peaceful resolution and escalating tensions to a catastrophic tipping point. In essence, this chapter illustrates the complex interplay of power, fear, and repression in Rwanda during a time of impending crisis. As the political climate deteriorated, societal divisions deepened, setting the stage for a horrifying escalation of violence that would soon engulf the nation. The narrative underscores how a combination of personal ambitions, societal superstitions, and political machinations collectively contributed to the conditions leading up to one of the most tragic genocides in history.

Key Point: The intricate web of power dynamics and societal divisions can inspire us to seek understanding and unity in our communities.

Critical Interpretation: As you reflect on the complexities of Rwanda's political landscape, consider how easily divisions can arise within your own community or workplace. Just as the Rwandan regime exploited fear and scapegoating, it serves as a poignant reminder of the importance of fostering open dialogue and empathy among diverse groups. Strive to replace mistrust with connection—find common ground with those whose perspectives differ from your own, and challenge any narratives that seek to pit you against each other. By actively working to bridge divides, you not only honor the lessons of history but also contribute to a more inclusive, understanding society where collective strength, rather than division, prevails.

chapter 7 |

In 1987, a significant shift occurred in Rwandan media with the launch of a newspaper named Kanguka, which translates to "Wake Up." This publication, spearheaded by a Hutu editor and a Tutsi businessman, diverged from the then-status quo by providing an economic rather than an ethnic lens through which to understand Rwandan life. Despite facing harassment, Kanguka garnered a loyal following among the literate population. In response, Madame Agathe Habyarimana, the President's wife, orchestrated the emergence of Kangura, a rival paper run by Hassan Ngeze, who capitalized on parody and propaganda to undermine Kanguka's credibility. The dual imprisonment of the editors from both publications drew international attention but served to bolster Ngeze's image as an anti-establishment figure. Even as he championed Hutu unity against the perceived Tutsi threat, Ngeze cleverly manipulated public sentiment and engaged in acts of self-promotion. His tactics included spreading disinformation about the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), the opposition group largely composed of Tutsi exiles. Ngeze's strategies fostered a climate of fear and divisiveness, ultimately steering Rwandan politics toward extreme Hutu nationalism. 1. Emergence of Ngeze and Hutu Power Ideology: Ngeze became an architect of Hutu supremacist ideology, most notably through the publication of "The Hutu Ten Commandments," which called for strict ethnic divisions and preemptive actions against Tutsis. This foundational document successfully resonated with the Hutu population, who were encouraged to reaffirm their identities through a lens of fear and hostility towards Tutsis. 2. Political Landscape Post-Arusha Accords: Following the signing of the Arusha Accords in 1993, which aimed to establish power-sharing between the government and the RPF, a volatile political climate ensued. Despite these attempts at peace, extremist Hutu factions, including Ngeze and the akazu, viewed the Accords as a betrayal and ramped up their rhetoric against Tutsis, consolidating their narrative as defenders of Hutu supremacy. 3. Ramping Up of Violence Against Tutsis: Evidence of hate and violence against Tutsis escalated, with the government orchestrating brutal massacres under the guise of self-defense. Such violent episodes were often preceded by political meetings that incited fear and hatred toward the Tutsi population, presenting them as enemies of the state in an organized and systemic campaign. 4. The Role of Propaganda: Radio stations like RTLM became instrumental in disseminating hate speech, echoing the frustrations of the Hutu populace while maligning Tutsis. This radio propaganda effectively mobilized the public’s arming and participation in violence, framing the narrative around a necessity for defense against a purported Tutsi conspiracy. 5. Final Preparation for Genocide: As political tensions heightened, Hutu extremists prepared for larger-scale violence, co-opting state resources and citizen militias to facilitate a broader campaign against Tutsis. The historical context of ethnic rivalry, coupled with modern political theorizing, laid the groundwork for what would become one of history's most brutal genocides. The unfolding of these events portrays a tragic and intricate interplay of media manipulation, political disintegration, and societal complicity that culminated in widespread atrocity. The Hutu Power ideology, led by figures like Ngeze, did not merely exploit existing tensions but actively constructed a perilous narrative that would lead Rwanda to the brink of catastrophe.

Key Point: The Danger of Divisive Narratives

Critical Interpretation: As you reflect on the rise of propaganda and the destructive impact of the Hutu Power ideology, consider how it serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of divisive narratives in our own lives. Just as Ngeze manipulated public sentiment and fueled an atmosphere of fear and hostility, you can observe the ways in which societal discourse can reinforce divisions among people today. This chapter inspires you to question the narratives that surround you, pushing you to seek connections rather than divisions, cultivate empathy, and create spaces for understanding. By actively engaging in dialogue that celebrates our common humanity, you can counteract the forces that seek to splinter communities and work towards a more inclusive and compassionate society. Embrace the responsibility you have to foster unity in your relationships, as even small efforts can lead to significant changes in your immediate environment.

chapter 8 |

In the chilling narrative of Rwanda on the brink of genocide, the experiences of individuals like Odette and the critical observations of General Dallaire illuminate the pervasive sense of dread and foreboding prevalent in early 1994. Their stories paint a vivid picture of a nation teetering on the edge of catastrophe, where trust in authorities was swiftly eroding amid mounting violence and rising hate. 1. As tensions escalated in Rwanda, Odette's harrowing encounter with the interahamwe—a militia composed of Hutu extremists—underscored the real and immediate dangers faced by Tutsis. After narrowly escaping an attack during which grenades were thrown at her car, her disillusionment with UNAMIR—the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda—was palpable. Despite assurances from General Dallaire that assistance would be available, his failure to respond that night confirmed her worst fears: they could not rely on help meant to protect them. 2. The distrust toward UNAMIR was palpable among both the Hutu moral architects of the impending genocide and the Tutsi population they targeted. The inaction of UN peacekeeping forces, highlighted by the humiliation of previous missions in places like Somalia and Bosnia, bred skepticism on both sides. The bitter acknowledgment of UNAMIR's limited mandate—restricted to self-defense and lacking the necessary firepower—created a vacuum that the interahamwe were poised to exploit. 3. As the clock ticked down to the genocide, Dallaire's dangerous intelligence reporting became crucial. His efforts to alert the UN about a concerted extermination plan orchestrated by Hutu Power dynamics, including details about the recruitment and training of militia members, went unheeded. His urgent plea for protection of a key informant, who had warned about plans to register Tutsis for extermination, was met with bureaucratic dismissal from UN leadership. This inaction tragically illustrated the gap between the ground realities in Rwanda and the responses from New York. 4. The warnings in Dallaire's fax reflected not just an acute awareness of imminent violence but a foreboding of an orchestrated campaign against the Tutsi people. Despite presenting compelling evidence, including detailed strategies for assassination during public events meant to provoke conflict, the UN's response was one of denial and redirection—advising Dallaire to inform Habyarimana of the potential threat rather than act decisively to prevent the unfolding horror. 5. As the month of March turned into April, an eerie collective intuition gripped the people of Rwanda. Individuals like Odette and Paul Rusesabagina expressed foreboding feelings, aware that something catastrophic was looming but unable to pinpoint exactly what it was. This shared yet unarticulated anxiety foreshadowed the impending violence. Reports of violence against Tutsis and political opposition grew, yet many Rwandans maintained hope for a resolution, despite the overwhelming sense of dread in the air. 6. The rising tension culminated in the days leading up to the genocide. Key figures in Hutu Power, emboldened by incendiary propaganda, openly discussed the necessity of violence. Publications like Kangura fueled the fire, eerily predicting political unrest and inciting violence against the Tutsi population. The newspaper's inflammatory rhetoric further enflamed divisions within Rwandan society, setting the stage for the atrocities that would soon unfold. Together, these accounts not only underscore the tragic missed opportunities for intervention but also reflect the pervasive atmosphere of fear and suspicion that characterized Rwanda in its final days before catastrophe. The testimonies reveal the tragic irony of silence amid impending violence—a silence that would soon echo through the devastations of genocide.

Key Point: The importance of vigilance and proactive engagement in the face of oncoming danger.

Critical Interpretation: Odette's experience and General Dallaire's observations remind us that ignoring the warning signs of injustice and violence can have catastrophic consequences. In your life, this echoes the necessity of being vigilant—both in recognizing the subtle shifts in societal attitudes towards exclusion and hatred and in understanding the importance of standing against such forces before they escalate into larger conflicts. It calls upon you to not just be a passive observer but to actively engage in your community, advocate for those who are marginalized or threatened, and ensure that the lessons from history are not forgotten. By fostering a culture of awareness and action, you contribute to a society where empathy and justice triumph over fear and division.

chapter 9 |

On the evening of April 6, 1994, Thomas Kamilindi, a Hutu journalist, felt the joy of celebrating his thirty-third birthday with his wife, Jacqueline, who had baked a cake for the occasion. However, the mood shifted dramatically when news broke that President Habyarimana's plane had been shot down, signaling the onset of chaos and impending violence in Rwanda. As fear gripped the nation, Thomas hunkered down, aware that large-scale massacres against the Tutsi population were being planned. He had cultivated relationships that afforded him insight into the plans of Hutu extremists, but he never anticipated the assassination of the president. In another part of Kigali, Odette and her husband Jean-Baptiste were alerted to the danger by a friend tuning into RTLM, a Hutu Power station notorious for inciting violence. As news of the assassination spread, Jean-Baptiste insisted that the family leave the city amidst the chaos. They faced significant obstacles, including a reluctance to abandon Odette's sister, Vénantie, a Tutsi representative in Parliament, who believed she was safe. When RTLM proclaimed a call for all citizens to stay in their homes, their fate began to match the growing reports of horror enveloping Rwanda. Amid the turbulence, Paul Rusesabagina, a hotel manager who was out at the time of the assassination, learned from his wife about the missile that struck the plane. The city's streets quickly transformed into scenes of terror as roadblocks emerged, manned by armed militias and soldiers eager to enact violence. As Paul sought refuge in his hotel, he discovered it filled with desperate individuals, mostly Tutsis and opposition figures seeking safety from the impending slaughter, yet even there, danger lurked just beyond the threshold. While the assassination led to a rapid power grab by Hutu extremists, the international community faltered in its response. As the Hutu regime moved swiftly to cement control, they systematically targeted Tutsis and Hutu opposition members. Clubs and grenades became tools of terror, as neighbors betrayed neighbors, and ordinary citizens joined in the brutality inspired by propaganda. The violence, encouraged by messages from the radio and community leaders, spiraled into widespread atrocities, with reports of rape and looting surging alongside the slaughter. Though the Hutu extremists sought to exterminate the Tutsi population, pockets of resistance existed. Individuals like Paul leveraged their connections with military officials to negotiate for the lives of refugees within the confines of the Mille Collines hotel, where an uneasy sanctuary formed amidst the despair. As chaos reigned, Odette and her family faced greater peril, navigating a city choked with blockades and death. Seeking escape to a relatively safer region, they witnessed the gruesome realities of the genocide firsthand. The family confronted harrowing situations where they were forced to negotiate with their captors, clutching onto life against overwhelming odds. In a grim parallel, Thomas faced his own brushes with death, grappling with his status as a target due to his journalistic integrity and Hutu ethnic identity. Threatened by soldiers, he maneuvered through life-threatening situations with a remarkable mixture of courage and pragmatism, persistently refusing to bow to fear. As the genocide unfolded, Bonaventure and his family sought refuge, ultimately hiding in the austere confines of a church where chaos enveloped the city outside. The disintegration of social norms became evident as individuals once trusted turned hostile, leaving Bonaventure reliant on the kindness of a sympathetic priest for survival. Paul remained a cornerstone of hope for many fighting for survival, persistently working to secure safe passage for those trapped in peril, even while navigating danger himself. His actions, while riddled with moral dilemmas, underscored a steadfast commitment to humanity amidst chaos. Through dramatic stories and intense moments, the harrowing truths of April 1994 emerged, weaving a tapestry of fear, survival, and the tug of humanity in the darkest of times. The chaos that unfolded in Rwanda remains not just a history of brutality but also a testament to the capacity for both evil and kindness inherent in human nature. Each narrative displays the fragility of life, the costs of hatred, and the resilience of individuals refusing to succumb to despair.

Key Point: The Power of Individual Action in the Face of Chaos

Critical Interpretation: In the darkest hours of crisis, like those during the Rwandan genocide, the actions of individuals can shine brightly as beacons of hope and humanity. Paul Rusesabagina’s courageous efforts to protect and negotiate for the lives of others amidst unimaginable horror remind you that even in perilous circumstances, your choices can profoundly impact the lives of those around you. When faced with adversity or conflict, you might find inspiration in Paul's relentless commitment to preserve dignity and life, urging you to act with compassion and integrity, to stand up against injustice, and to fiercely protect the vulnerable. This pivotal lesson can guide your actions in everyday life, motivating you to cultivate connections, foster understanding, and be a beacon of strength for others in their moments of need.

chapter 10 |

In recounting the harrowing events surrounding the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Chapter 10 of Philip Gourevitch's "We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families" highlights the efforts of Paul Rusesabagina, the manager of the Hôtel des Mille Collines, to shelter Tutsi refugees amid widespread violence and bloodshed. 1. The Fax Machine as a Lifeline: In 1987, the hotel acquired a fax machine, a seemingly mundane detail that became crucial during the genocide when outside communication was cut off. Rusesabagina discovered that the fax line still worked, allowing him to reach international authorities, including the King of Belgium and the U.S. President. He tirelessly used this lifeline, often working late into the night to secure help for his guests while carefully safeguarding its operation from the Hutu Power leaders, who had other pressing concerns amid the chaos. 2. Personal Stories of Danger: Among the guests was Thomas Kamilindi, who gave an interview detailing the dire conditions at the hotel, including shortages of basic necessities and the violence enveloping the city. This courage put him at risk when a soldier sent to kill him warned him to flee. Despite the threats, people found refuge at the hotel, and Rusesabagina's steadfast refusal to comply with the demands to turn over guests marked a remarkable stand against the genocide. 3. Scale of the Atrocities: The chapter also starkly outlines the magnitude of the violence—an estimated 800,000 people killed in a mere 100 days, with the majority of killings occurring in the first few weeks. During this period, the Hôtel des Mille Collines served as a rare sanctuary, where nearly a thousand lives were inexplicably spared. 4. Radio Propaganda and Widespread Fear: Those who sought refuge were not immune to the horrors erupting around them. Bonaventure, hiding in a nearby church, listened to RTLM broadcasts inciting more violence, illustrating the pervasive fear and societal breakdown. Reports from Canadian physician James Orbinski paint a grim picture of Kigali, with roadblocks manned by men armed with alcohol-fueled aggression, and hospitals turned into death traps, further emphasizing the struggle for survival. 5. Clerical Complicity: Figures like Father Wenceslas embodied the moral complexity of the time. While he was armed and acted as a protector, he also capitulated to the surrounding violence, reflecting the moral failings of those in positions of influence. Rusesabagina's conversations with him reveal the tragic contradiction between the calling of a priest and the human instinct for self-preservation in the face of overwhelming evil. 6. Mixed Messages from the Church: The chapter critiques the complicity of church figures like Bishop Misago, who offered rationalizations for their actions (or inaction) during the genocide. Despite being an influential leader, he downplayed his agency and responsibility, suggesting he was a victim of historical momentum rather than a perpetrator of inaction—a sentiment echoed by others who failed to intervene decisively. 7. Hope and Despair: Amidst the despair, Rusesabagina's efforts to protect his guests became emblematic of hope. His refusal to turn away those seeking shelter showcased a poignant human spirit in horror-stricken circumstances, although he felt isolated in his commitment amid widespread complicity. 8. Evacuations and Continued Danger: The chapter culminates in the struggles to evacuate refugees from the hotel, highlighting the fraught interactions with armed gangs and military forces. An attempted UN evacuation turns chaotic, showcasing the thin veneer of safety afforded by international responders, who often found themselves entangled in the very violence they sought to quell. Paul's story reveals not only his courageous defiance but also the broader moral quandaries faced by individuals and institutions during the darkest moments in Rwandan history. Ultimately, Chapter 10 of Gourevitch's book serves as a haunting reminder of the fragility of humanity amidst overwhelming evil and the extraordinary acts of resistance that can arise even in the bleakest circumstances.

chapter 11 |

In the twelfth chapter of Philip Gourevitch's "We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families," the author reflects on the haunting silence and eerie scenes in post-genocide Rwanda. The narrative begins with an unsettling observation: the absence of dogs in a country where they had once been commonplace. As Gourevitch recalls his early months in Rwanda, he notes the stark contrast between the vibrant life he expected and the grim reality he encountered. Days after the horrifying genocide of Tutsis, he learns that dogs were largely eradicated, their elimination tragically linked to the decay of humanity during the conflict. As Rwandan soldiers shot stray dogs consuming corpses, the deep moral implications of this act seem to echo the broader atrocities occurring around them. 1. Gourevitch remarks on the historical indifference of the international community towards Rwanda, contrasting the rhetoric of the United Nations and the Genocide Convention—declarations designed to prevent such horrors—with the stark inaction that characterized the organization's response to the genocide. He notes that while human beings lost their lives in vast numbers, a tragic failure of moral responsibility unfolded on the world stage, particularly evident in the lack of intervention by outside powers. 2. The withdrawal of Belgian troops, following the murder of ten soldiers, marked the beginning of the UN's significant retreat from its mission in Rwanda. Gourevitch details how Major General Dallaire, the commander of the UN peacekeeping mission, had warned that an appropriately equipped force could halt the genocide, but his requests went unheeded. Instead, the UN Security Council opted for drastic cuts to troop levels, leaving the remaining staff with a severely limited mandate. The ramifications of these decisions highlighted a stark disparity between the interests of powerful nations and the human plight unfolding in Rwanda. 3. This political neglect was perpetuated by the United States, which sought to avoid entanglement in Rwanda due to pressing memories of military failures in Somalia. The Clinton administration, under pressure from its policymakers, obstructed efforts to send reinforcements to support UNAMIR while simultaneously fostering a narrative that deflected the use of the term “genocide.” This deliberate manipulation of language became an insidious means of preventing the obligations enshrined in the Genocide Convention from being enforced. 4. As the conflict evolved, France's intervention under the guise of humanitarianism raised complex moral questions. French troops, erroneously deemed saviors, soon found themselves entangled with the very forces that had executed the genocide. The operation, although initially aimed at protection, ultimately complicated the humanitarian situation further, as French support shielded many of the perpetrators and allowed the genocide to continue in the backdrop of a supposed peacekeeping mission. 5. Through poignant imagery and stark language, Gourevitch captures the horror of the camps in Zaire, where the aftermath of genocide intersected with the plight of the Hutu refugees. These camps, intended to be places of safety, became breeding grounds for violence and retribution, blurring the lines between victim and perpetrator. The complexity of human experience emerged vividly as desperate people, fleeing their pasts, reestablished power dynamics predicated on fear. 6. In the narrative’s conclusion, Gourevitch highlights the consequence of the international response to humanitarian crises, exemplified by Rwanda, as a failure of conscience. The disconnection between the rhetoric of humanitarian responsibility and the realities of political leverage underlines the profound challenges in addressing atrocities. The chapters culminate with a somber reflection from General Dallaire, who emphasizes a need for genuine engagement, transcending mere acknowledgment of suffering to a commitment to meaningful action. Gourevitch's reflections resonate as a haunting reminder of the past, compelling readers to confront the painful truths of humanity's capacity for violence and the ongoing struggles against indifference and inaction in the face of such tragic history. The cacophony of war, silence of the dead, and voices of the living serve as a continuous call for remembrance, awareness, and, ultimately, responsibility.

chapter 12 |

In an evocative exploration of the complexities surrounding the Rwandan genocide, the narrative begins with the words of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who emphasizes a collective African shame in response to atrocities committed in Rwanda. This perspective, while meant to foster solidarity, is met with skepticism by some, reflecting the broader complexities surrounding national identity and accountability in the region. The author, reflecting on the contradictions of life in Rwanda, engages in driving through the picturesque landscape, where vibrant daily life seems to persist despite the deep scars left by violence. 1. Ambiguity of Identity: The interaction with the people of Rwanda serves as a reminder of the ambiguity surrounding individual identities with respect to the genocide. The author reflects on how the vibrant life of Rwandans conflicts with the dark histories they carry, leaving one unsure who among the children they encounter might have been a survivor or a perpetrator of the violence. 2. Socioeconomic Strain: The narrative highlights the historical context contributing to the environment that led to the genocide, notably the longstanding socio-economic pressures exacerbated by overcrowding and competition for resources. While some argue that such conditions could be catalyzing factors for the horrors of genocide, the author questions the assumption that economic strife inevitably leads to mass violence, noting that not all overpopulated regions have witnessed similar atrocities. 3. Complexity of Historical Forces: The text delves into the multifaceted historical roots of the genocide, from colonial legacies to the internal political struggle marked by waves of violence. The author suggests that the catastrophic events of 1994 were not merely a product of economic desperation but rather a culmination of deep-seated ideologies and historical inequalities that had metastasized over decades. 4. The Role of Politics: A significant theme is the misuse of power and the importance of narrative in the exercise of authority. The author articulates that power can distort reality, with the potential for extreme corruption when concentrated. In the context of Rwanda, this concentration and polarization of power facilitated narratives used to justify genocide, indicating a stark departure from the principles of democracy and citizenship. 5. Understanding the Aftermath: As the narrative transitions to reflections on the aftermath of the genocide, the stark realities of Rwandans grappling with loss and memory emerge. The complexities of rebuilding a society marked by such profound violence invite contemplation of human nature and resilience. The author notes that the stories shared by survivors signify a struggle not only to understand the past but to find meaning in the continuous present, illustrating the ongoing impact of history on the living. 6. The Challenge of Interpretation: The author critiques journalistic portrayals of the situation in Rwanda that suggest moral equivalence between Hutu and Tutsi victims, arguing that such narratives fail to capture the gravity of the genocide and the ideological underpinnings that led to it. By emphasizing that not all narratives are equally valid, the text challenges readers to engage critically with the information they receive about complex socio-political situations. Ultimately, this chapter paints a vivid portrait of Rwanda as a nation caught between a tragic past and an uncertain future, where life continues amid echoes of profound loss. The journey reflects not merely on the events of the genocide but on the indelible mark it leaves on the collective psyche of a people navigating the legacies of their histories. Through poignant imagery and thoughtful exploration of identity and power, the narrative invites continued reflection on the nature of humanity and the complexities of reconciliation in the wake of unimaginable tragedy.

chapter 13 |

In the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, the complexities and cyclical nature of violence are explored through the lens of the Kibeho camp incident, which showcases the tragic interplay between mercy and vengeance. Initially, the narrative highlights the grim reality of violence in Rwanda where Hutus killed Tutsis, subsequently leading to a subsequent pattern where Tutsi forces avenged the atrocities. This violence is often portrayed in a simplistic manner, devoid of a nuanced understanding of the political landscape that fostered such brutality. The author delves into the tragedy at Kibeho, a camp established for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the wake of the genocide, where the presence of former perpetrators posed continual threats. The humanitarian narrative around these events typically condemns violence universally; however, it raises significant questions about comparative atrocities. The text discusses notions of justified violence within historical contexts, prompting a reconsideration of human rights standards when relating to the aftermath of such far-reaching disasters. As the RPA (Rwandan Patriotic Army) sought to disband the camp amidst fears of threats posed by hard-core génocidaires, the international community, including UN forces, grappled with how to approach the situation. Tension within the camps escalated, leading to disorganization and violent confrontations culminating in chaos. The author recounts the harrowing details of the violence as the RPA undertook operations to resettle IDPs, often leading to a mix of brutality by soldiers and panic by the camp residents. The narrative spotlights the chaotic environment, where violence erupted amid a heavy military presence, resulting in an overwhelming number of deaths and injuries in what began as an operation meant to restore order. The chaos was exacerbated by misinformation and the extreme fear among the IDPs, leading to stampedes and subsequent fatalities not only from gunfire but also from melee attacks with machetes, echoing the horrors of genocide. The aftermath also reflects on the psychological toll on humanitarian workers, as individuals attempt to reconcile their roles in a landscape of overwhelming loss and barbarity. Their experiences challenge the moral calculations surrounding the judgments of life and death in such a context, revealing the layers of guilt, compassion, and the haunting memories that accompany them. Ultimately, the exploration of the Kibeho incident acts as a stark reminder of the disintegration of humanity amidst mass violence and the long-lasting consequences of revenge cycles. It leaves readers confronted with the realities of both individual and collective suffering, examining the paradox of mercy in a landscape marred by hatred and the question of whether true justice can ever be achieved in such deeply fractured societies.

chapter 14 |

In Chapter 14 of "We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families" by Philip Gourevitch, the narrative delves into the complex social dynamics of Rwandans, particularly focusing on Paul Kagame's formative years and the broader implications of identity within Rwanda’s tumultuous history. 1. The chapter opens with a recollection of Kagame's youth in Uganda, seen through the eyes of a former schoolmate who describes him as an exceptionally skinny refugee rather than an aristocratic Tutsi. This characterization sets a backdrop to understanding Kagame's identity shaped by exile and the sociopolitical landscape of the time, where Hutu and Tutsi identities were influenced by historical experiences rather than inherent traits. 2. As Kagame grew up in Uganda, he and other Rwandan refugees navigated an environment where their identities as exiles bonded them rather than divided them. This reflection highlights how, during their time outside Rwanda, the lines of ethnic division blurred, allowing for a collective Rwandan identity to emerge amidst shared hardships. 3. Kagame's early experiences were marked by violence as he witnessed Hutu mobs attacking Tutsi homes before his family's escape to Uganda. This trauma instilled in him a sense of dispossession and the desire to reclaim rights as a Rwandan citizen, a theme that persisted through the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) movement he would later lead. 4. The chapter then explores Kagame's journey through military training in Uganda, where he rapidly ascended due to his intelligence and strategic prowess. Here, the tensions faced by Rwandan refugees intensified due to rampant xenophobia and political persecution, and the lack of international support further fueled their grievances. 5. Kagame's bond with contemporaries like Fred Rwigyema illuminated their shared aspirations for liberation, which drove them to join the Ugandan military and subsequently to establish the RPF, aimed at reclaiming Rwandan sovereignty during Habyarimana's oppressive regime. 6. The narrative progresses to portray Kagame's military acumen, particularly how he effectively transformed the RPF into a disciplined and ideologically driven army. The chapter emphasizes that the RPF was not just an armed group but a disciplined force committed to political change, equipped not only with military drills but also political education aimed at fostering responsible leadership. 7. As the RPF captured power following the genocide, a complex relationship emerged with the concept of liberation, where they aimed to navigate the challenges of rebuilding a war-torn society while facing the specter of reprisal and unresolved injustices stemming from the genocide. 8. Kagame’s diplomatic navigation set him apart as he sought a path of reconciliation despite ongoing tensions and potential retaliatory violence from within the community. He expressed commitment to establishing a new Rwandan narrative that transcended the ethnic divisions perpetuated by past atrocities. 9. The chapter concludes with an incisive reflection on the trials of survivors, particularly Bonaventure Nyibizi, who faced the challenge of reconciling his existence with the weight of loss amid a ravaged society. The overarching message resonates with the broader theme of survival, emphasizing the psychological toll of trauma that transcended mere physical existence. Through these interconnected reflections, Chapter 14 vividly captures the layers of identity, trauma, and the complexities of nation-building faced by the Rwandan people in the wake of profound violence, centering on Kagame's leadership and the RPF’s vision for a unified Rwanda.

chapter 15 |

In the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, the landscape was marked not only by physical ruin but also by immense emotional and social upheaval. The survivors, orphaned and isolated, sought companionship and solidarity in makeshift communities formed amidst the remnants of their former lives. In a landscape littered with devastation, more than a hundred thousand children were left to care for one another, while adults like Bonaventure not only worked tirelessly to rebuild their lives but also started adopting children to restore some semblance of family in the chaos. 1. The Burden of Trauma: Survivors, many of whom lost family and friends, grappled with deep-seated trauma. Bonaventure's perspective highlighted the urgency of finding purpose as a means of healing, emphasizing the importance of staying busy to combat idleness and despair. The new government found itself in a precarious position, with nearly no resources or functioning infrastructure to support a nation in crisis. With hospitals destroyed and public services non-existent, the immediate task of restoration seemed daunting. 2. The Exodus and Return: Contrary to expectations, the diaspora of Tutsi exiles began returning in droves, compelled by an intrinsic desire to reclaim their homeland, despite the devastation. The sheer scale of this migration—over seven hundred and fifty thousand Tutsi returnees—indicated a complex interplay of historical longing, determination to defy genocide, and opportunistic motivations driven by the need for rebuilding. The returnees brought goods and skills, reviving the economy and helping to reintegrate essential services despite the staggering loss of life around them. 3. Compounded Divisions: Upon their return, Tutsi returnees encountered not only the haunting absence of familiar faces but also feelings of alienation within their own country. There was a growing chasm between those who had survived the genocide and the newcomers, with some expressing disdain for the survivors who had stayed behind. Complaints arose over perceived privileges granted to returnees, while those who had endured the atrocities felt marginalized. This division illustrated the complexities of identity and belonging in a nation trying to piece itself back together amidst lingering mistrust. 4. The Fragility of Coexistence: As the dynamics shifted within communities, old tensions bubbled to the surface. Hutus and Tutsis found themselves navigating a landscape rife with suspicion and fear, irrespective of their shared history. Survivors were often regarded with skepticism, and the once-familiar bonds began to fray as new narratives of victimhood and guilt developed. Amid these prevailing emotions, discussions of reconciliation emerged, but many found such notions premature and misguided, especially under the weight of unprocessed grief and trauma. 5. Personal Stories of Loss and Healing: Through personal accounts like that of Odette and Edmond, the profound toll of the genocide is starkly illustrated. Odette faced the insurmountable pain of loss and the difficulties of reintegration as she and her family adopted orphaned children, while Edmond confronted the haunting memories of his family's slaughter. The stories reveal the struggle between the desire for healing and the inability to forget the past—a dichotomy that defined the experience of many Rwandans. Odette's reflections on her fears and the heartbreaking realities of her children's trauma evoke a palpable sense of sorrow and frustration within the community. In essence, the journey of rebuilding Rwanda post-genocide encompassed not just rebuilding infrastructure but navigating the complex emotions surrounding loss, identity, and the quest for belonging in a fractured society. As Rwandans grappled with their past while striving toward a future, the deeply entrenched scars left by the genocide continued to shape the fabric of their collective identity. Through resilience and a yearning for connection, Rwanda emerged as a testament to the indomitable spirit of humanity amidst adversity, though with the understanding that true reconciliation would be an ongoing challenge, fraught with delicate feelings and unresolved grievances.

chapter 16 |

In Rwanda, the aftermath of the 1994 genocide left a profound impact on its prison system, which was initially abandoned but quickly became overcrowded with individuals accused of participating in the atrocities. By April 1995, over thirty-three thousand individuals faced arrest, a number that surged to sixty thousand by the year's end, and climbed even higher in subsequent years, resulting in at least one hundred twenty-five thousand prisoners by late 1997. Rwanda’s central prisons, originally designed for twelve thousand inmates, were overwhelmed, leading to appalling conditions. Despite the dire circumstances, prisoners often exhibited unexpected calmness and camaraderie, suggesting a phenomenon of social order despite the chaos outside. Many inmates were found to have internalized the authority structure that had governed Rwanda prior to the genocide. Within prison walls, a hierarchy reemerged, with more privileged prisoners enjoying better conditions while the majority languished in overcrowded spaces. Raids and escapes were rare, possibly due to a general perception among prisoners that their situation was preferable to facing external threats, especially given ongoing fears of retaliation from the new regime. General Kagame, the head of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, openly discussed the challenge of punishing those responsible for the genocide. Acknowledging that nearly a million individuals might have participated in varying degrees, he grappled with the moral implications of arresting and imprisoning potentially innocent people while also seeking justice for the victims. His approach emphasized the idea of prioritizing the prosecution of those he deemed primary offenders—the masterminds—while considering lesser offenders differently. The decision to release some individuals, like Placide Koloni, who held political office during and after the genocide, sparked tensions. Koloni's subsequent murder illustrated the deep-seated fears and political volatility still present in a society attempting to rebuild. As many government officials resigned in protest over ongoing violence, the fear permeated even the highest ranks of the government, intensifying the sense of instability. Prison conditions were also dire, particularly in notorious Gitarama, where thousands of individuals were confined in appalling overcrowded conditions, exacerbating physical ailments and suffering. While some improvements were noted, the overall health crisis remained severe, with high mortality rates due to preventable diseases. Frustrations with the inadequacies of the justice system emerged as another challenge. Rwanda faced an overwhelming caseload with limited judicial capabilities. Arrest procedures were often disregarded, leading to accusations based merely on hearsay. Trials were almost nonexistent, and when they did occur, they were fraught with challenges, including an inadequately resourced legal system. The prevailing question for Rwandans, particularly survivors, was how to obtain justice without further violence. The government sought to redefine justice not through traditional means but by integrating community-based approaches and focusing on reconciliation through accountability. Acknowledging the psychological impacts of the genocide, the government attempted to educate the population on the importance of justice intertwined with healing. While attempts were made to honor and acknowledge those who had protected Tutsis during the genocide, political infighting often stymied such efforts. Post-genocide, the focus shifted toward rebuilding a sense of national identity stripped of colonial and genocidal mentalities. The government promoted the idea of fostering new societal norms, distancing from the fear-based systems that had dominated the past. International efforts to prosecute key figures of the genocide became a point of contention. The establishment of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was met with skepticism as it indicated a lack of faith in the Rwandan judicial system. The tribunal’s procedures, often perceived as politically driven, highlighted a disconnect between international expectations and the realities on the ground in Rwanda. Furthermore, the ban on the death penalty sparked outrage, as many Rwandans believed that perpetrators deserved the harshest punishments for their crimes. In examining these complexities, it becomes evident that achieving justice and reconciliation in Rwanda was a multifaceted endeavor, caught between the need for accountability and the reality of societal rebuilding. The lingering presence of unpunished crimes created an undercurrent of frustration and resentment, making true reconciliation a daunting task in the wake of such profound horror. It highlighted the delicate balance between forgiveness and justice, reconciliation and retribution, leaving the nation grappling with the scars of its past as it sought a path forward.

chapter 17 |

In this excerpt from Chapter 17 of "We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families," author Philip Gourevitch presents a complex interplay between culture, humor, politics, and the aftermath of genocide in Rwanda. 1. The chapter opens with a casual conversation between Gourevitch and an RPA colonel, highlighting the absence of comedians in Rwanda. The colonel attributes this to a lack of humor in a nation burdened by adversity, noting that Rwandan jokes lack the comedic flair found in other cultures. Instead, the discussions yield a deeper exploration of the intellectual and logical structures inherent in Rwandan humor. Gourevitch reflects on the reasons behind the apparent stagnation in Rwandan cultural expression compared to its East African neighbors, suggesting that political turmoil has overshadowed artistic development. 2. The conversation quickly shifts to the serious challenges that Rwanda faces in moving beyond its historical traumas, particularly the genocide and the old mentalities that still pervade society. The colonel expresses a feeling of discouragement, indicating that while jokes exist, they reflect a complex struggle with traditional values versus aspirations for a modern identity. This conflict exemplifies the broader societal tensions in post-genocide Rwanda, where the paths of history, culture, and politics are intricately connected. 3. Gourevitch then introduces a narrative involving a Hutu who, after the genocide, seeks anonymity while discussing the pervasive dishonesty within Rwandan society. This man articulates a belief that Rwandans often speak in dual languages; one for outsiders and another amongst themselves, steeped in secrecy and distrust. Such remarks are echoed by Colonel Dr. Joseph Karemera, who identifies the cultural trait of deceit as “ikinamucho,” indicating how that culture of dishonesty is deeply rooted and problematic. 4. The chapter delves into specific figures within Rwandan politics, highlighting Théodore Sindikubwabo, the interim president installed shortly after the assassination of President Habyarimana. Gourevitch recounts how Sindikubwabo's actions incited violence in regions that had previously been safe, emphasizing the rapid turn into chaos and brutality that characterized the genocide and its aftermath. Despite Sindikubwabo’s attempts to distance himself from responsibility for the massacres, his expressions ring hollow, underscoring the obfuscation and betrayal that marked Rwandan leadership during that period. 5. As Gourevitch visits the Zaire camps, he reveals the uncomfortable reality of humanitarian efforts being twisted into support for Hutu Power. Aid organizations inadvertently bolster the regime's propaganda and serve to keep its power structure intact despite the considerable abuses and injustices occurring within the camps. Humanitarian responses become complex, as aid is given without proper vetting, leading to situations where perpetrators are aided while victims remain marginalized. 6. The text highlights the contradictions present in the international humanitarian response to the Rwandan crisis. While proclaimed intentions to aid refugees exist, many aid workers acknowledge that their contributions have enabled the continued existence of Hutu Power ideologies and militancy among the populations in the camps. This moral quagmire serves as a significant critique of how well-meaning actions can produce detrimental effects, complicating the pathways to recovery for Rwandans. 7. Finally, the narrative reflects on the deep psychological scars left by the genocide, demonstrating how the past influences contemporary Rwandan identity and governance. Gourevitch presents a grim acknowledgment of the role of deception—both personal and political—as a weapon that continues to shape Rwandan lives and perceptions. The book closes with a powerful reminder of the cyclical nature of violence and the urgent need to break free from historical grievances to forge a more honest future. The chapter illustrates a poignant exploration of the ambiguities and moral challenges surrounding culture, truth, and reconciliation in post-genocide Rwanda, emphasizing the importance of confronting the past to build a healthier future.

chapter 18 |